28 May 1864–13 June 1924

Charles Alphonso Smith, author and educator, was born in Greensboro, the third son of Dr. Jacob Henry, a Presbyterian minister, and his second wife, Mary Kelly Watson Smith, the daughter of Judge Egbert Reid Watson of Charlottesville, Va. Named for two brothers of his father who died in the Civil War, he signed his name C. Alphonso Smith but was called Phon by his family and friends. One of his closest boyhood friends was William Sydney Porter, better known as O. Henry, who was a member with him in a Serenading Society. In 1880 Smith went to Davidson College, which his two older brothers were already attending; he, like them, at the end of four years was graduated Phi Beta Kappa. He was extremely popular with his fellow students, who carried him on their shoulders in triumph at commencement when it was announced that he had won two medals. From 1884 to 1889 he taught school in the three small towns of Sanford, Selma, and Princeton, taking one year off to earn an A.M. degree from Davidson in 1887. He entered Johns Hopkins University in 1889 and received his Ph.D. four years later. His published dissertation, The Order of Words in Anglo-Saxon Prose (1893), was dedicated to his father, "whose sympathy and scholarship" were both an inspiration and a goal.

In 1893 Smith was appointed professor of English at Louisiana State University, where he remained for the next nine years except for a sabbatical taken abroad in 1900–1901. In 1902 he became head of the department of English at The University of North Carolina, and the following year he was made the first dean of its graduate school. To encourage graduate scholarship at the university, he founded and edited Studies in Philology. On 15 Nov. 1905, he married Susan McGee Heck, the daughter of Colonel Jonathan Heck of Raleigh; they had two sons and one daughter. By 1909, when the University of Virginia appointed him its first Edgar Allan Poe Professor of English, he had acquired an international reputation. The following year (1910–11) he was invited to be Theodore Roosevelt Exchange Professor at the University of Berlin. In 1917 Smith became head of the department of English at the U.S. Naval Academy, the first civilian to hold such a post. He was the recipient of LL.D. degrees from the Universities of Mississippi and North Carolina, and the L.H.D. degree from the University of Cincinnati.

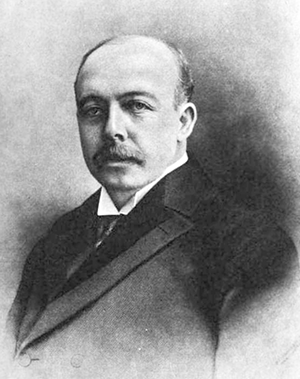

Tall, balding, with a reddish-brown mustache, Smith was an outstanding teacher, and many of his students became heads of America's foremost English departments. F. Stringfellow Barr, a former student, called him "essentially dramatic" and said that he inspired students through the force of his personality, communicating to them his own love of literature and research. These same traits made him a successful lecturer. Before leaving Louisiana he was asked to give a farewell address to the state legislature, and Dr. Archibald Henderson, a colleague at The University of North Carolina, called him "the best lecturer on literature I ever heard." Throughout his life he was in demand at universities, seminaries, and chautauquas in all parts of the country. People were introduced to literature, not only through his teaching and lecturing, but also through his best-selling book, What Can Literature Do For Me? (1913), which sold over 100,000 copies and showed his craftsmanship in the use of the striking, telling phrase.

Smith was a prolific scholar; a bibliography of his books and articles runs to more than one hundred titles. He was associate editor of the ten-volume World's Orators (1901) and of the twenty-seven-volume Library of Southern Literature (1907 [portrait in vol. 14]), as well as the author of numerous philological works on grammar and syntax. But he is best known as an authority on the American short story and as a folklorist. He had lectured on the short story in Germany and published many books and articles on it in America. The most important was O. Henry Biography (1916), the first major study of his boyhood friend, which President Theodore Roosevelt declared to be "almost as good as O. Henry, himself."

The most lasting contribution of C. Alphonso Smith may have been as a pioneer collector and popularizer of the oral prose, verse, and songs of the South. His love of people, his musical ability (he relaxed by playing the banjo, composing music, and singing), and his training in philology ideally suited him for this role. He was the founder of the Virginia Folklore Society in 1913 and was one of the first to see the importance of collecting the music as well as the words of ballads to determine the earliest version. His interest in folklore went back many years to when he had been associate literary editor of the Library of Southern Literature and personally responsible for volume 14, entitled Miscellanea. It contained, not the acknowledged belle lettres, but rather the vernacular literature of the South drawn from tombstone epitaphs, sermons, ballads, spirituals, banquet toasts, rural humor, and so forth—sources and categories usually ignored by academic scholars. At a time when the genteel tradition ruled academic circles and German historical and philological methodology reinforced an underlying belief in Anglo-Saxon superiority, this unorthodox interest in the literature of blacks and poor whites must have shocked many of his colleagues. But Smith, believing in "the glory of the commonplace," felt that without turning to such sources, the history of the nation's literature could not be adequately written. "Dixie" and "The Star Spangled Banner" were important, he said, not for the greatness of their poetry, but for what they told of the nation's culture and values.

His teaching position at the U.S. Naval Academy appealed to Smith because he envisioned that the young officers would be ambassadors to the world of the democratic values he believed in and saw reflected in the literature of the American people. Stricken suddenly by "a complication of organic trouble," he sent word to the saddened cadets [*]preparing to leave on their annual summer cruise, "Tell the boys that I have started on a great adventure; I greet the unknown with a cheer." In accordance with his wish, a spiritual was sung at the funeral. He was buried in Greensboro's Green Hill Cemetery. A memorial plaque at Annapolis, inscribed with words from one of his books, describes the impact he had on his generation: "What he received as mist, he returned as rain."