13 Nov. 1812–18 Oct. 1894

Edwin Godwin Reade, jurist and Confederate senator, was born at Mount Tirzah, Person County, the son of Robert R. and Judith A. Gooch Reade. The father, a yeoman farmer, died early and the children were forced to seek work. While studying at home under his mother, Edwin worked as a farm laborer, in a tannery, and at a carriage shop. At age eighteen he entered an academy in Orange County, then one in Granville, where he served as an associate teacher. Afterwards he read law at home from books borrowed from a retired lawyer and was admitted to the bar in 1835. Reade eventually became one of the most brilliant speakers and successful lawyers of his era. He also managed a small plantation near Roxboro, which, in 1860, was worked by nineteen people Reade enslaved. He also owned other property valued at $50,000.

Reade was originally a Whig, but in 1855 he joined the American party because of its anti-Catholic and antiforeign positions. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1855 but disliked the work and declined to seek reelection. During his term he witnessed Preston Brooks's savage caning of Charles Sumner; when the House voted to censure L. M. Keitt for attempting to prevent anyone from interfering in the fracas, Reade was the only Southerner voting for censure. Reade was such a strong Unionist that he was sounded out for a place in Abraham Lincoln's cabinet, but he declined the honor and proposed his friend John A. Gilmer instead. His Unionism persisted even after Lincoln's call for volunteers to force the seceded states back into the Union, and he refused to become a candidate for the May Secession Convention. In 1863 he was elected to the superior court, but before his term began, Governor Zebulon B. Vance prevailed upon him to serve the remaining months of George Davis's term as Confederate senator.

Reade took his seat on 22 Jan. 1864 and was appointed to the Committee on Finance. During his two months in the senate he made the most of his opportunity to safeguard his state against what he considered unwarranted Confederate encroachments. On 23 January, when the state's delegation had an interview with President Davis, Reade warned him to "trust North Carolina and let her alone." A week later he described to the senate the rampant dissatisfaction in his state and warned that it might undertake separate peace negotiations if the trend towards military rule continued. His voting record indicated that he opposed virtually all the emergency laws then before the senate. Reade sought reelection as a peace candidate, but he was too much of a states' rights extremist even for the North Carolina General Assembly.

In 1865 Reade was president of the Johnson Reconstruction convention, and in the same year he was elected associate justice of the state supreme court. Although he was now a Republican, both parties elected him to the same position in 1868 and continued to reelect him until 1879. Among his important decisions were ruling that homestead exemptions were valid against debts contracted before the law was adopted and that the governor rather than the legislature had the power of appointment to office. Reade retired from the bench to become president of a Raleigh bank, and his expert management rescued it from probable bankruptcy. He was grand master of Masons in the state in 1865 and 1866. He died in Raleigh and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

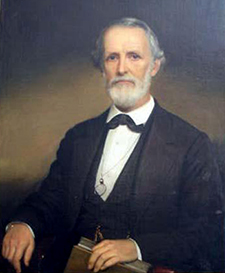

Reade was a tall, handsome man, albeit of a rather cold personality. He spoke in simple phrases with a clear voice and as a lawyer went for the jugular. His judicial opinions were brief and lucidly written. His first wife was Emily A. Moore of Person County. After she died in 1871, he married Mrs. Mary Parmele of Washington, N.C. There were no children by either marriage.