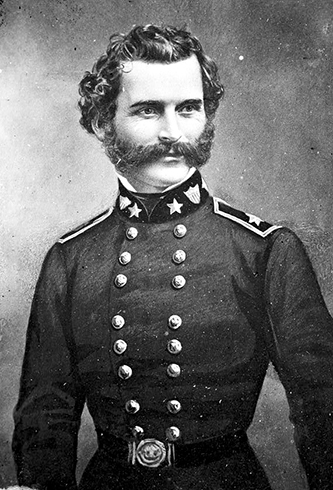

4 June 1803–6 Aug. 1881

Gabriel James Rains, career soldier, Confederate general, and inventor, was born in New Bern, Craven County, the elder son of Gabriel M. and Hester Ambrose Rains. His brother, George Washington Rains, founded the Confederate gunpowder mill at Augusta, Ga. After his early education, Gabriel Rains entered West Point Military Academy on 1 July 1822. Graduating thirteenth in his class on 1 July 1827, he became second lieutenant of the Seventh Infantry Regiment and saw service in the West, mainly Indian Territory. On 28 Jan. 1834 he became a first lieutenant and on 25 Dec. 1837 he was promoted to captain.

In 1839 Rains took part in the Seminole War in Florida. Commanding a company of men at Fort King, he first began to experiment with explosives. The Indians harassed and beleaguered the garrison to such an extent that Rains in desperation rigged a live shell hidden under a blanket in the woods near a pond where the Indians went to get water. Some Indians set off the trap and were killed. Rains soon set a similar trap and when it was heard to explode, led a party of men out to investigate. It was discovered that the bomb had done no harm but as the group returned to the fort it was attacked by about a hundred Indians. Rains skillfully handled his men, however, and the Indians were repulsed though Rains himself was shot through the body and so badly wounded that announcements of his death were published. Nevertheless, he recovered and was promoted to brevet major on 28 Apr. 1840 for gallantry and meritorious conduct in the attack.

Upon returning to duty Rains served at posts in Louisiana and Florida and in the military occupation of Texas. In the Mexican War in 1846 he gave the deciding vote in a council of officers at Fort Brown against capitulation to General Ampudia. Rains participated in the defense of the fort and in the Battle of Rasaca de la Palma. Afterwards he was detailed to recruiting duty, at which he was quite successful. In 1849–50 Rains fought in a second Seminole War, and on 9 Mar. 1851 he was promoted to major of the Fourth Infantry Regiment. Sent to California the following year, he earned a reputation as an Indian fighter and on 5 June 1860 was made lieutenant colonel of the Fifth Infantry Regiment.

At the outbreak of the Civil War Rains resigned his commission on 31 July 1861 and offered his services to the Confederacy. He was commissioned a colonel in the Regular Confederate Army and on 23 Sept. 1861 was appointed brigadier general from North Carolina to rank from the same date (confirmed 13 Dec. 1861). Rains was then assigned to command the First Division of General John Magruder's army defending the Department of the Peninsula, which consisted of the Thirteenth and Twenty-sixth Alabama regiments and the Sixth and Twenty-third regiments. This command later became a brigade of General D. H. Hill's division. Rains commanded at Yorktown during the winter of 1861–62 and here continued his experiments with mines. He developed a type of subterranean mine (called "torpedoes") patterned after a design by Samuel Colt, and these were placed at a salient angle and other points along the earthworks that were considered to be accessible to the enemy. Rains even put mines in the nearby waters of the York River to discourage enemy naval operations.

When George B. McClellan's Union army finally forced the evacuation of the Yorktown defenses at the beginning of May 1862, Rains's brigade constituted part of the rear guard as the Confederate army retreated towards Richmond. His men hungry and exhausted from constant Union pursuit, Rains found outside Williamsburg a broken-down ammunition chest that contained several artillery shells fitted with percussion fuses. He had these quickly buried in the road. Pursuing Union cavalry trod on the shells and detonated them, causing a few casualties. Union troops entering the abandoned defenses of Yorktown also set off some of the mines Rains had left behind in the earthworks, causing about thirty casualties. All in all these devices made pursuing Union forces act with caution, and both the Northern press and General McClellan bitterly denounced their use as an improper means of warfare. McClellan described it as "the most murderous and barbarous conduct in placing torpedoes," and the Northern papers carried stories of booby traps being placed in wells, around houses, in bags of flour, in carpetbags, and what not. General Joseph E. Johnston, the Confederate army commander, read some of the stories in these newspapers and asked for comment from Rains. Rains, of course, took credit for the mines left in the works and placed in the road but denied using booby traps. General James Longstreet, Rains's wing commander, in writing out orders for Rains's brigade on 11 May 1862, requested that Rains not use any more mines because he did not recognize it as a "proper or effective method of war." But Rains protested and went over Longstreet's head to report to Secretary of War George W. Randolph. Rains defended his use of explosive devices as a means to discourage a night attack by an enemy, to defend a weak point of a line, to check enemy pursuit, and so forth. General Hill, Rains's division commander, added an endorsement saying that he believed any means of destroying the enemy was legal in warfare. Secretary Randolph's decision on the matter was that such explosive devices were admissible to check pursuit, defend a work, or sink a ship, but were not allowable for the sole purpose of killing enemy soldiers. He further added that if Rains and Longstreet disagreed, Rains should yield to his superior or transfer to the river defenses, where the use of explosive devices was "clearly admissible."

On 31 May 1862 Rains participated in the Battle of Seven Pines outside Richmond, where his brigade brilliantly outflanked a Union position known as "Casey's Redoubt" and thus enabled the Confederate forces to sweep the Union troops from the field. Rains was unable to advance farther, however, and drew criticism from General Hill because of this. After the battle, Rains was transferred to the submarine defenses of the James and Appomattox rivers on 18 June 1862 to continue his experiments with explosives. During the summer he was briefly in charge of the defenses of the Cape Fear River in North Carolina, and on 16 Dec. 1862 he was assigned to head the Bureau of Conscription in Richmond. While in service here Rains began to formulate plans for the torpedo defense of Confederate ports. These were presented to President Jefferson Davis, who was much impressed and transferred Rains from the Bureau of Conscription on 25 May 1863 and directed him to put his plans into operation. Rains was first sent to Vicksburg, Miss., and then to Charleston, S.C., and Mobile, Ala. From then until the end of the war he worked to bolster the defenses of the major Southern ports with torpedoes and mines.

Rains was formally appointed chief of a newly created Torpedo Bureau on 17 June 1864 and remained in this position until the close of the war. Under his supervision torpedo factories were established at Richmond, Wilmington, Mobile, Charleston, and Savannah. His men filled beer kegs or barrels with gunpowder, fitted them with a percussion primer at each end, and then set them adrift to strike against an enemy vessel and explode. Other types were developed to be anchored to the harbor bottom and fired from a wire leading to shore. Rains also invented an autosubterranean explosive shell for land use, complete with a tin shield for protection against the rain. Despite the fact that leaders early in the war had objected to the use of mines on moral grounds, these devices were widely employed by the end of the conflict. Some 1,300 such shells were buried in the defenses of Richmond. In addition, Rains invented a machine for manufacturing gun caps.

His torpedoes were a great success. They provided an effective deterrent to Union naval attack, and they sank about fifty-eight Union vessels. Greater damage might have been done had the Confederacy been willing to put effort and money into torpedo defense earlier in the war. Perhaps Rains's greatest accomplishment in the use of explosives occurred on 9 Aug. 1864, when two of his agents exploded a bomb at the wharfs of Ulysses S. Grant's supply base at City Point, Va., causing a high loss of life and $4 million in damages.

After the war Rains lived for a time in Atlanta before moving to South Carolina, where he worked as a clerk from 1877 to 1880 in the Quartermaster's Department of the U.S. Army at Charleston. He died in Aiken, S.C. Rains had married Mary Jane McClellan, a granddaughter of Governor John Sevier. They had six children.