26 Dec. 1841–15 Apr. 1910

Romulus Zachariah Linney, lawyer and congressman, was born in Rutherford County, the son of William Cope and Martha Baxter Linney. His father was a well-to-do farmer; his mother was a sister of John Baxter, legislator, speaker of the House of Commons, and judge. Linney attended the local common schools and York Collegiate Institute. On 29 May 1861, at age nineteen, he enlisted in Company A, Seventh Regiment, North Carolina Troops, and served in the Civil War until he was seriously wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. On 15 December he was discharged because of the permanent nature of his injury. Afterwards he read law under an attorney in Taylorsville, was licensed by the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1868, and opened a practice in Taylorsville to serve the surrounding area.

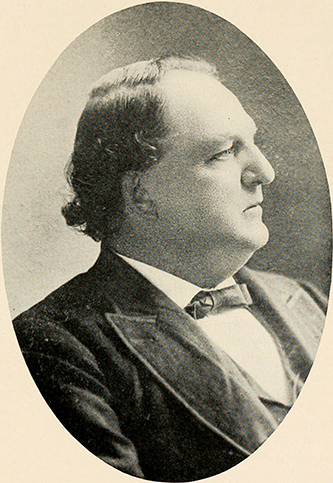

Linney quickly gained a reputation as a skilled orator and held audiences spellbound in the courtroom. He came to be recognized as a colorful character and was widely known throughout the state. Entering politics, he served as a Democrat in the North Carolina Senate for three terms (1870–72, 1874–75, and 1883). In a subsequent campaign he was defeated by William H. H. Cowles, a Republican. Linney felt that he had been double-crossed by the Democratic party and ran for Congress as an independent in the Eighth District. Switching his party affiliation, he finally won in 1894 and served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1895–1901) as a Republican. Linney was a part of the Republican-Populist fusion as some of his opinions fell clearly into the Populist camp.

On several occasions his speeches created a sensation on the floor of the House. He lived up to his nickname, "Bull Moose" or "the Bull of the Brushies," from the Brushy Mountains in which his district lay. His bull-like domination of the courtroom and his antics on the floor of Congress were often commented on. He had a knack for illustrating his remarks with folksy, amusing stories that served to simplify the point he wished to make. He was a master at calling upon the great authors of the past for apt quotations and being able to draw suitable passages from his reading to clinch an argument.

Popular with his constituency, Linney supported local causes and on one occasion contributed five hundred dollars to the Appalachian Training School at Boone; a quotation from one of his addresses was carved in marble over the front door: "Learning, the Handmaid of Loyalty and Liberty. A Vote Governs Better than a Crown." He maintained his ties by traveling through his district in a buggy drawn by two matched black ponies and stopping from time to time to visit some old friend. In debate concerning the internal revenue system, he represented the views of his mountain supporters; these people often tried to supplement their limited income by distilling brandy and whiskey outside the law. They were hurt by the excise tax that the federal government placed on spirits, and throughout his career Linney tried to change this form of taxation.

Congressman Linney's views on the coinage of money were those of the Populists. He supported the free coinage of silver until the Republicans under President William McKinley announced in favor of the gold standard. Linney then switched his support to the gold standard. When questioned about this change, he answered in typical Linney style that the only two things that never changed an opinion were "a dead horse and a live ass."

In the field of foreign affairs he was inclined to vote with the majority. He supported the declaration of war against Spain in the Spanish-American War and the annexation of Hawaii. However, he did not favor the occupation of the Philippines because he feared that the people there were too different from Americans. Among other subjects, Linney spoke in favor of a protective tariff and against the crime of lynching.

With the conclusion of the Fifty-sixth Congress in 1901, Linney retired from public service and resumed his law practice in North Carolina.

In 1864 he married Dorcus A. Stephenson and they became the parents of a son, Frank Armfield. Linney suffered a fatal heart attack at age sixty-nine and was buried in Fairview Cemetery, Taylorsville.