17 Nov. 1842–22 Feb. 1922

![Engraved portrait of Wilson Gray Lamb, from Samuel Ashe's <i>Biographical History of North Carolina</i>, Volume 7, [p. 280-281], published 1908 by Charles L. Van Noppen Publisher, Greensboro, North Carolina. From the collections of the Government & Heritage Library, State Library of North Carolina.](/sites/default/files/images_bio/Lamb_Wilson_Gray_Ashe_Vol7_GHL.jpg)

Wilson Gray Lamb, Jr., political leader, merchant, and Confederate soldier, was born in Elizabeth City, one of the four sons and five daughters of W. G. Lamb of Pasquotank and Martin counties and his wife, Eliza Williams. Members of the family moved to the region from New England before the American Revolution. A direct ancestor was Colonel Gideon Lamb of the Sixth Regiment, North Carolina Continental Brigade, during the Revolution. Young Lamb's only formal education was at the school conducted in Elizabeth City by the Reverend Edward M. Forbes, rector of Christ Church. He had been tendered an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy and had passed the entrance examination when summoned home by his father at the outbreak of the Civil War.

In March 1862 Lamb enlisted as a private in the newly redesignated Seventeenth North Carolina Regiment for service in the company commanded by his older brother, Captain John S. Lamb. He became sergeant-major of the unit on 17 May 1862 and eventually was named regimental adjutant, though never commissioned to the post. In December 1863 he was commissioned third lieutenant. When the regiment was in brigade around Petersburg, Va., in 1864, Lamb commanded a skirmish line and was wounded on 18 June. During the repulse of Union forces along the North East River following the evacuation of Wilmington, he was remembered "as displaying coolness and conspicuous bravery." He also distinguished himself during engagements in the Kinston area, participated in the Battle of Bentonville, and was among the forces of General Joseph E. Johnston surrendering at Centre Church in Randolph County in April 1865.

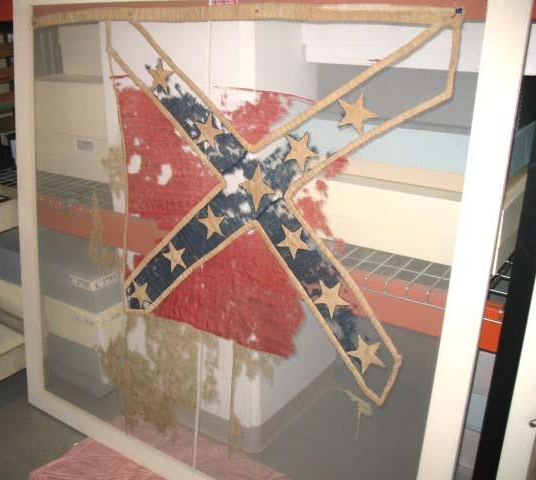

Conspiring with Abel Thomas to conceal the colors of the Seventeenth Regiment in Thomas's saddle blankets, Lamb helped to smuggle the banner past Federal sentries at Chapel Hill and carried it home to Martin County. There he had it framed and displayed in his Williamston residence for half a century; he donated it to the Hall of History in Raleigh about 1915. Lamb was the author of the history of the regiment published in Walter Clark's history of the Civil War units from North Carolina.

Settling in Williamston after the war, Lamb was the chief manufacturer's representative in the state for Daniel Miller and Company, Baltimore wholesalers. A strong Democrat in politics, he represented the party at the national conventions of 1884, 1892, and 1912. He also was a longtime member of the state Democratic executive committee and of its central committee. On one occasion he declined to become a candidate for governor. As chairman of the State Board of Elections from its founding in 1901, he was complimented several times by Republican leaders for the impartiality of his rulings. "He always hit above the belt," one observer commented," no matter how bitter the struggle."

Lamb was a member of the Episcopal church, serving as vestryman and senior warden of the Church of the Advent in Williamston from 1868 until 1918 and several times as a delegate to the denomination's General Convention. He resigned as senior warden only after his seventy-sixth birthday. His principal avocation was his membership in the North Carolina Society of the Cincinnati, through descent from Colonel Gideon Lamb. He became a charter member when the society was revived in Raleigh in 1896. Named its first president, he retained that office until his death. In 1913 he headed the society's North Carolina delegation to the White House where he inducted President Woodrow Wilson into honorary membership.

On 7 June 1870 at Hamilton, Lamb married Virginia Louisa Cotten and they became the parents of three sons and five daughters. A portrait of him hangs in the headquarters of the General Society of the Cincinnati in Washington, D.C. He was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, Williamston.