23 Nov. 1860–24 July 1944

Edward Austin Johnson, educator, historian, attorney, and politician, was one of eleven children born to Columbus and Eliza Johnson. Columbus Johnson and his wife Eliza were enslaved in Wake County, thus Johnson was born enslaved. Johnson acquired his earliest education from a free Black woman, Nancy Walton, and after emancipation attended a school in Raleigh directed by two white teachers from New England. These "Yankee" teachers introduced him to the Congregational church, in which he was active for the rest of his life.

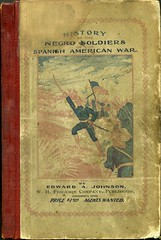

In 1879 Johnson entered Atlanta University and upon graduation four years later became principal of the Mitchell Street School in Atlanta. In 1885 he returned to Raleigh to head Washington School, a position he held until 1891. As a principal and teacher, he came to recognize the critical need for works that would provide Black children with information about "the many brave deeds and noble characters of their own race." To fill the void, Johnson wrote A School History of the Negro Race in America which was published in 1891 and later appeared in several revised editions. This textbook was the first by a Black author to be approved by the North Carolina State Board of Education for use in the public schools, and it established his reputation as a scholar and historian. Johnson was the author of several other books, including History of the Negro Soldiers in the Spanish-American War, Light Ahead for the Negro, and Negro Almanac and Statistics, as well as numerous articles and pamphlets.

While a principal in Raleigh, Johnson enrolled in the law school at Shaw University and received a bachelor of law degree in 1891. Two years later he joined the law faculty at Shaw where he remained until 1907, serving first as professor and later as dean. Johnson acquired an enviable reputation as a trial lawyer and won all of the numerous cases that he argued before the North Carolina Supreme Court. Referring to his success as an attorney, a contemporary observed that "no man stands higher in the esteem of the substantial people of the Old North State than Mr. Johnson."

Johnson also was associated with various business ventures. In 1897 he joined Warren C. Coleman and other Black businessmen in North Carolina to establish a cotton mill in Concord. Johnson served first as vice-president and later as president of the Coleman Manufacturing Company, which was intended to become a model of Black initiative and business acumen. The company did not fulfill the expectations of its incorporators and in fact ultimately went bankrupt. In 1898 Johnson and six other Black men organized the North Carolina Mutual and Provident Association in Durham which in time became the largest Black-owned insurance company in the world. By the turn of the century, he had accumulated considerable real estate in Raleigh and in 1902 was one of only two Black residents of the city whose income was sufficient to warrant payment of the state's income tax.

Throughout his career Johnson was active in the Republican party. He figured prominently in the party's local and state organizations and was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1892 and 1896. He was a member of Raleigh's Board of Aldermen for a term, and he served from 1899 to 1907 as assistant to the federal attorney for the district of eastern North Carolina. Unwilling to accept Booker T. Washington's advice that Black people should eschew politics, Johnson deeply resented the disfranchisement of Black citizens that resulted from the rise of white supremacy across the state in 1898. This led Johnson to leave North Carolina for New York City.

Opening a law office in Harlem in 1907, Johnson quickly established a lucrative practice and became prominent in the economic, social, and political life of the Black community. An active member of the Harlem Board of Trade and Commerce and the Upper Harlem Taxpayers Association, he also contributed generously of his time and money to the expansion of recreational facilities for Black youth. Programs sponsored by churches and by the YMCA were of special concern to him.

In Harlem, Johnson proposed that Black people should be nominated for office in areas where they constituted a majority of the voters. His own rise to political power in New York "symbolized a major transition in American Negro and urban history," as he was a Black southerner who escaped some limitations on his civil and political rights by migrating to a northern city. He served as Republican committeeman from Harlem's Nineteenth Assembly District and in 1917 was elected to the state assembly in Albany, becoming the first Black member of the New York legislature. As a legislator, according to a report by the Citizens Union, he "promoted measures of importance to his constituency." Of the four bills he piloted through the legislature, Johnson considered two of far-reaching significance: a civil rights act and a law establishing a state employment bureau. Defeated for reelection largely as the result of a redistricting of the city, Johnson remained active in local Republican circles. His final attempt to gain elective office took place in 1928, when he waged a vigorous, though unsuccessful campaign as a Republican candidate for Congress.

During the last decade of his life, Johnson was almost blind. He died at age eighty-three following surgery and was survived by his only child, a daughter.