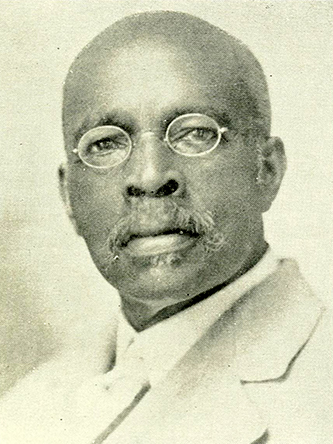

9 Jan. Ca. 1852–4 Sept. 1931

Charles Norfleet Hunter, educator, was born in Raleigh at the home of his father, Osborne Hunter, a black artisan. His mother, Mary Hunter, was an enslaved woman who was enslaved by William Dallas Haywood of Raleigh. Despite this, she lived with her husband until her death in 1855. At that time young Hunter, his older brother, and his two sisters were taken to Haywood's property and cared for by their aunt.

At the close of the Civil War, Hunter enrolled in a freedmen's school in Raleigh. He later stated that he had completed one year of course work at Shaw University and the University of South Carolina. For the most part, however, his formal education was limited to occasional summer sessions at Hampton Institute in Virginia and teachers' institutes in North Carolina.

By 1869 Hunter was employed at the Raleigh branch of the Freedmen's Savings and Trust Company. He was assistant cashier when the company failed in 1874. In December of the following year he began teaching at Shoe Heel (Maxton) in Robeson County. In 1878 he became principal of the Garfield School in Raleigh, but resigned three years later to accept a clerkship in the Raleigh post office. After the election of a Democratic president in 1884, Hunter found employment as a traveling agent for A. S. Barnes & Co. of New York. But he soon returned to teaching, first at the grade school for black students in Durham and then as principal, successively, of the school for black students in Goldsboro and the Oberlin and Garfield schools in Raleigh.

Hunter lost his position at the latter school in 1900, apparently because of a drinking problem. He moved to Trenton, N.J., where he was a partner in a real estate and employment agency. In 1902 he returned to Raleigh as principal of the Oberlin School. Transferring to the Chavis School in 1906, he worked also for the North Carolina Mutual and Provident Association as traveling agent and superintendent of the Raleigh office. In 1909 he was appointed principal of the school for black students at Method, which under his leadership became the Berry O'Kelly Training and Industrial School.

Moving to Portsmouth, Va., in June 1918, Hunter obtained employment in the Norfolk Navy Yard. He returned to Raleigh in 1921, but his age and lack of formal education made it increasingly difficult for him to secure and retain teaching positions. Between 1922 and 1931 he was principal of schools for black students in Garner, Haywood, Pittsboro, Wilson's Mills, Manchester, Lumber Bridge, and Palmyra.

Throughout his career, Hunter was involved in numerous activities and organizations intended to promote progress for black Americans and friendly relations with white people. He and his brother, Osborne Hunter, Jr., were among the founders of the North Carolina Industrial Association, which sponsored the first black state fair in North Carolina in November 1879. Hunter was active in reforming and reviving the black state fair after its suspension in 1926 and was elected secretary and manager of the fair in 1930. As secretary of the North Carolina state organization of the Negro Development and Exposition Company, he was also involved in preparing exhibits for the Jamestown Exposition in 1907.

Hunter wrote numerous articles and letters for newspapers, many of them concerning race relations and the history and progress of black people. He also edited a number of newspapers and periodicals. During the 1880s he was an editor of The Journal of Industry, weekly paper of the North Carolina Industrial Association, and of The Progressive Educator, official organ of the North Carolina State Teachers' Association. In 1891 he became associate editor of the Raleigh Gazette ; in 1902 he began publishing the Oberlin School Record ; and in 1910 he edited Our Advance, a short-lived monthly. From March 1917 until his departure for Portsmouth, and again in 1921, he edited the Raleigh Independent.

For many years Hunter was secretary of the Negro Republican State Executive Committee. He was severely critical of the lily-white Republican organization and actively opposed the appointments of Frank A. Linney and I. M. Meekins to federal judicial posts in the state in the early 1920s. At various times Hunter was also secretary of the Grand Lodge of North Carolina of the Independent Order of Good Templars, recording secretary and book agent for the North Carolina State Teachers' Educational Association, corresponding secretary of the state Negro Business League, and a member of the vestry of St. Ambrose Episcopal Church, Raleigh.

In November 1876 Hunter married Eliza Hawkins (d. 1923), a native of Warrenton who had moved to Raleigh after the Civil War. Of their five children, two survived to adulthood: Emma Hunter Satterwhite and Lena M. Hunter. Charles N. Hunter died and was buried in Raleigh.