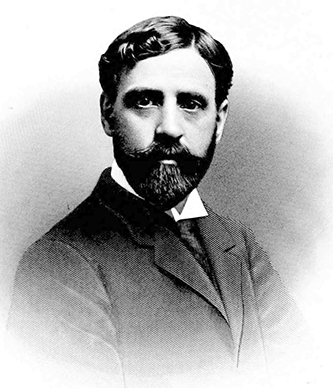

2 May 1862–13 Aug. 1906

Egbert Barry Cornwall Hambley, mining engineer and industrialist, was born in Penzance, Cornwall, England, the son of James and Ellen Read Hambley. His father was a civil engineer who had explored mining regions throughout the world, including South America and Africa. E. B. C. Hambley, like his father, pursued a career in civil and mining engineering. He studied at Trevath House School in Cornwall and at the Royal School of Mines in Kensington. At the death of his father in 1880, Hambley left school and began working for J. J. Truran, a businessman whose enterprises extended throughout the British Empire.

In January 1881, he was sent to North Carolina and served as assistant to the principal of the Gold Hill Mines in Rowan County. This property had been among the most valuable gold mines in the state before the Civil War but was worked only intermittently after the war. Hambley remained at Gold Hill for three years, then returned to England to join a major engineering firm, John Taylor & Sons. In his capacity as special engineer, Hambley was dispatched to southern India, the Gold Coast and Transvaal in Africa, Mexico, California, Spain, and Norway. During this intensive three-year period, he became acquainted with the latest techniques of mining engineering and also with the design of power facilities.

He returned with this knowledge to North Carolina in 1887 and took up permanent residence (he was never naturalized), serving as a contact for British investment capital in the state. At one time, he was consulting engineer to no less than eight mining companies and managing director for the Sam Christian Hydraulic Company in Montgomery County. Hambley also promoted business and industry in the Salisbury vicinity. He organized the Salisbury Gas and Electric Light Company and served on the board of the Salisbury Cotton Mills, the Davis and Wiley Bank of Salisbury, and the Yadkin Railroad Company.

From 1898 until his death, Hambley's energies were absorbed by an ambitious project to harness the hydroelectric power of the Yadkin River and to develop an industrial complex in Stanly, Rowan, and neighboring counties. In partnership with local businessmen, he formed the North Carolina Power Company and began to search for potential investors. Shortly after 1900, Hambley engaged the interest of George I. Whitney, a financier from Pittsburgh and a member of the banking and brokerage firm of Whitney and Stephenson. Whitney purchased a controlling share of the power company and formed Whitney Company, with Hambley as vice-president and general manager. The Whitney Company served as an umbrella for several subsidiary enterprises, including the Whitney Reduction Works at Gold Hill, the Rowan Granite Company at what became Granite Quarry, the Barringer Gold Mining Company near New London, the Yadkin Land Company, the Yadkin River Electric Power Company, the Yadkin Mines Consolidated Company, and the Virginia Copper and Land Company. Textile mills and electric power outlets were also planned. Rights-of-way for power lines were secured as far away as Knoxville, Tenn.

Within the first few years of the twentieth century, the Whitney Company owned large tracts of land in Stanly and surrounding counties and had stirred the imagination of contemporary observers. Local newspapers saw the company as spearheading a "revolution in manufacturing," turning North Carolina's Piedmont into "the New England of the South." "The master minds at Whitney," exclaimed one journalist, "are engaged in carrying out a giant scheme to grapple with and subdue elemental nature, forcing her with many inventions to lend her untamed energy, wasted for ages, to the direction of human intelligence, that much good may result to the world of men."

The pivotal element in the Whitney-Hambley plan was a hydroelectric power dam at the Narrows of the Yadkin River. The dam, projected at 35 feet in height and 1,100 feet in length, was to generate 27,000 horsepower (the equivalent of about 20,000 kilowatts of electric power) to towns and industries throughout the Piedmont. A five-mile canal was also planned to connect the dam to a power plant on the river just below Palmer Mountain. A spur line was constructed from New London to the dam site. A model manufacturing town called Whitney was designed, and company engineers laid out streets and boulevards. Hundreds of workers, including Sicilian masons, were imported to build the dam out of huge granite blocks quarried in Rowan County.

Despite the prodigious labors of these men and the visionary concepts of Whitney and Hambley, the project stalled after the first few years. Accidents at company mines and at the dam site, as well as outbreaks of typhoid, depleted the labor force. Hambley himself contracted typhoid in the summer of 1906 and died at age forty-four. His death was a shock to the industrial and engineering community of North Carolina. The Charlotte Observer called it "a most deplorable event" and editorialized that "few men have done more for [North Carolina] in a material way, and his value to it and the extent of the loss it has sustained in his death are beyond estimate." The Whitney Company outlived Hambley by only one year. The panic of 1907 cut off George Whitney's lines of credit and, although he continued to operate some subsidiary companies for several years, the bold plan to harness the power of the Yadkin was abandoned. A decade later, the Aluminum Company of America implemented Hambley's basic concept with a new dam a few miles downstream to provide power for its reduction works at Badin.

In 1887 Hambley married Lottie Clark Coleman, the great-granddaughter of North Carolina's Governor William Hawkins. They had five children: Littleton Coleman, Gilbert Foster, William Hawkins, James Young, and Charlotte Isabel. The Hambleys first resided at the farm of Mrs. Hambley's father, Dr. Littleton W. Coleman, near Rockwell where Hambley bred valuable herds of Jersey cattle. In 1903, they moved to a large new home on Fulton Street in Salisbury. The house, designed by Charles C. Hook of Charlotte, was constructed not only to accommodate the growing Hambley family but also to entertain potential investors in the projects of the Whitney Company. Hambley had migrated to America as a member of the Church of England and belonged to the Episcopal church throughout his life. He was buried at Chestnut Hill Cemetery, Salisbury.