10 Apr. 1786–21 July 1860

Joseph Gales, Jr., editor and publisher, was born in Eckington, England, the eldest son of Joseph and Winifred Marshall Gales. He began school in Sheffield, England, where his father had established himself as a printer and newspaper publisher. From his mother, a classics scholar and novelist, he learned to read Latin fluently and to appreciate literature. In 1795, the family fled England for America, victims of the political unrest afflicting England during the French Revolution. Settled in Philadelphia, young Joseph resumed his education. In 1799 the family moved to Raleigh, when the elder Gales accepted an offer to publish a Jeffersonian newspaper in the new capital city of North Carolina.

The senior Gales had hoped that his son would receive a strong academic education in addition to training as a printer. With that end in mind, he enrolled Joseph in The University of North Carolina in the fall of 1800. But because of an altercation involving one of the literary societies on the campus, young Gales was expelled the next year. He returned to Raleigh and entered newspaper work with his father. There he improved his shorthand skill and knowledge of printing. In 1806, his father sent him to Philadelphia to work with William Young Birch, a printer and close friend of the elder Gales. Upon completion of this training Joseph received a diploma from the Typographical Society of Philadelphia.

In 1807 Samuel Harrison Smith offered to sell the National Intelligencer, the first newspaper established in Washington, D.C. The chance to gain control of the "Court Paper" of the Jeffersonian Republicans appealed to the elder Joseph Gales, who had known Smith while living in Philadelphia. He wrote Smith and asked if he would accept his son Joseph as a partner, with the understanding that if the young man proved able he would assume full ownership. Young Gales was only twenty-one, and his father felt he needed more experience before undertaking the task of editing and publishing a newspaper on his own. Smith hesitated, for he wished to retire altogether from newspaper work; but as he received no better offer he accepted. In the summer of 1807 Joseph Gales, Jr., joined the staff of the National Intelligencer. Three years later, in August 1810, he assumed full control.

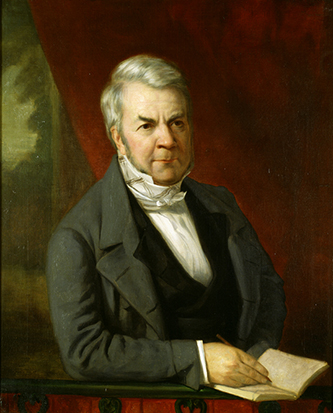

Gales was a short man, five feet two inches in height. He had a large head, with a broad face and thick black hair. His complexion was dark, his face dominated by black, piercing eyes. Harrison Gray Otis, the Massachusetts Federalist, wrote his wife that Gales "has very much the face & manner of a Malay." His employer's wife, Margaret Bayard Smith, in whose home he lived during his first years with the Intelligencer, thought the young man to be a "country bumpkin" and attempted to "soften" his manners. But another early acquaintance described him as "affable and easy," gracious, and exceedingly polite.

The National Intelligencer was one of the more important newspapers published in the United States, a reputation it enjoyed during its more than fifty years of existence. Under Smith's direction it had become the semiofficial voice of the presidency, a function it continued to serve through the administration of James Monroe. By the nation's newspapers, the Intelligencer was regarded as the basic source for news of the national government. When young Gales assumed control, the paper was issued as a triweekly.

In October 1812, Gales was joined in publishing the Intelligencer by his brother-in-law, William Winston Seaton. Seaton, a Virginian, had married Sarah Gales, the oldest daughter of Joseph Gales, Sr., in April 1809. Three months before that, in January, he had become associated with the elder Gales as coeditor of the Raleigh Register. The addition of Seaton to the staff of the Intelligencer lightened the work of Gales. On several occasions before this he had called on his father to help him report the affairs of Congress. Now these brothers-in-law divided the labor; in reporting the debates in Congress, performed exclusively by the two until 1820, Gales covered the Senate and Seaton the House. Then on 1 Jan. 1813 they began a daily edition, continuing to publish the triweekly for national circulation. During the War of 1812 the Intelligencer's office was sacked by the British in their raid on Washington, the only private establishment so treated. Gales's support of the war was given as the reason by Admiral Sir George Cockburn, the British commander. During this time the editors were on duty with the American forces defending Washington.

Gales married Sarah Juliana Maria Lee, the daughter of Theodorick Lee and niece of "Light Horse Harry" Lee, on 14 Dec. 1812 in Winchester, Va. They had no children but adopted a niece of Mrs. Gales named Juliana. Before he married Gales had selected a spot for a country home some two miles from the center of Washington. But until commercial development drove them out, the couple lived on Ninth Street not far from the Intelligencer office at Seventh and D streets, N.W. Eckington, the name Gales chose for his country estate, became the center for lavish entertaining as well as a refuge for the editor. Both the Gales and Seaton families were among the social elite of Washington. Numbered among Gales's close friends were Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Nicholas Biddle.

In its early years the Intelligencer supported the Jeffersonian Republicans. But with the disarray into which that party fell in 1824, Gales turned first to John Quincy Adams, and then, with the opening of the Jacksonian period, to Henry Clay and the Whig party. With the rise of the slavery controversy and the drift toward disunion, Gales tried to follow a neutral course. For nearly his whole career he argued for a policy of moderation regarding the slavery issue, urging the Northern states to leave the solution up to slaveholders and the Southern states. But toward nullification and secession, from the Hartford Convention on, Gales was implacably opposed. This stand in the 1850s threatened the very life of the Intelligencer, for a majority of the paper's subscribers lived in the South.

Gales was usually given credit for the "sound conservatism" of the Intelligencer's editorials. Daniel Webster wrote that Gales "knows more about the history of this government than all the political writers of the day put together." It was Webster's opinion that the editorials printed in the Intelligencer and widely reprinted by newspapers in all sections of the nation helped win support for the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842. James Polk believed Gales's refusal editorially to oppose ratification of the treaty with Mexico was an important factor in securing acceptance of that treaty in 1848.

Beginning in 1825, Gales and Seaton began the Register of Debates in Congress, an annual record of congressional proceedings. To many people this series, which continued through 1837, was the most valuable publishing contribution made by the two editors of the Intelligencer. Of equal importance, however, were the American State Papers, the first volume issued in 1832, a collection of the major documents dealing with foreign relations, Indian affairs, and other matters. This thirty-eight-volume series has been termed by one historian "the high-water mark of historical publication . . . up to the period of the Civil War." Another publishing venture of note undertaken by Gales and Seaton was the Annals of Congress. The first two volumes, published in 1832, were edited by Joseph Gales, Sr., who had retired as editor of the Raleigh Register and moved to Washington. Publication was resumed in 1849. It was completed in 1856, totaling forty-four volumes.

These publishing activities of Gales and Seaton were heavily subsidized by Congress, a testament to the political friendships enjoyed by the editors. Indeed, it was this patronage that enabled the Intelligencer to remain in business while operating as an opposition newspaper. Yet the paper was never a financial success. Neither Gales nor Seaton was a good enough financier to build up the business side of the Intelligencer. During the Jacksonian period the editors were heavily indebted to the United States Bank, an institution they warmly supported along with the American System of Henry Clay.

Both Gales and Seaton were active in the affairs of Washington, Seaton more so than Gales. From 1827 to 1830 Gales served as mayor of the city. He was also active in the American Colonization Society and a member of the first Unitarian church organized in the nation's capital. Though Gales no longer reported the debates in the Senate, Webster asked him to report his debate with Hayne in 1830.

Physically, Joseph Gales, Jr., was never a strong man. In fact, it was an extended illness suffered in 1812 that led to the decision by Gales and his father to invite Seaton to become a partner in publishing the Intelligencer. There were further bouts with sickness, and by the early 1850s Gales was badly crippled. Nevertheless, he lived to be seventy-four. His funeral, held at his home Eckington, was a state occasion. President Buchanan and his cabinet attended as a body, along with other dignitaries. Schools and stores were closed. He was buried in the Congressional Cemetery. Seaton survived him by six years and the Intelligencer by nine.