1705–8?–13 July 1766

John Dalrymple, army officer, the second surviving son of Sir John Dalrymple of Cousland, second baronet, and his wife, Elizabeth Fletcher, probably was born in Edinburgh.* His great-uncle, John Dalrymple, second Viscount Stair, was created Earl of Stair; his great-grandfather was the first Viscount Stair. Both of these men were active politically in Scotland and England and both were privy councillors.

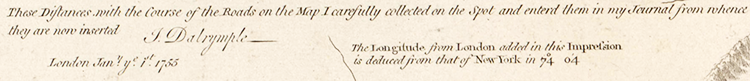

Dalrymple was an officer in the British army as early as 1733. He probably was the one of this name who served as a volunteer for five years in General Sir David Colyear's regiment of foot in the Dutch service in Flanders where he was made an ensign. Afterward Major General Thomas Wentworth, who spoke highly of him, made him a lieutenant. In June 1740 Dalrymple was in New Hanover County, N.C., where he served as a juryman; late that year and in 1741 he participated in the combined British and colonial expedition against Cartagena. He returned to North Carolina and in September 1744 bought 550 acres on the north side of Old Town Creek in New Hanover (now Brunswick) County. This represented an addition to property that he already owned, as his will made 25 Feb. 1743 mentioned extensive land including his plantation known as Spring Garden. He saw service outside the province for several years, however, and in the early 1750s was associated with Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, the father of Thomas, in Virginia. Fry and Jefferson were engaged in surveying and mapping the territory along the North Carolina-Virginia boundary in the west. Dalrymple served as a quartermaster officer under Fry. Colonel Fry died in 1754 and was succeeded by a young officer named George Washington; during that summer Dalrymple went to London where he arranged for the publication in 1755 of the Fry-Jefferson map. Known as the "Dalrymple" edition, it contained extensive new information about western North Carolina and the trans-Allegheny region.

Returning from London early in 1755, Dalrymple, now a captain, delivered some letters to Governor Robert Dinwiddie in Virginia. Through Dinwiddie's friendship with General Edward Braddock, commander in chief of British forces in America, he secured the appointment of Dalrymple on 17 Mar. 1755 as commander of Fort Johnston at the mouth of the Cape Fear River in North Carolina, a post Dalrymple seems to have held before his service in Virginia. After some years, Dalrymple obtained leave from the commander to visit England; while in London he secured a new commission from the king, dated 27 Oct. 1760, naming him commander of Fort Johnston. Upon returning to his post he discovered that Governor Arthur Dobbs was displeased with him for having left the province without first obtaining the governor's permission. Dalrymple informed Dobbs that he was not under the governor's authority, only under that of the commander in chief of the forces in America. In what must have been an unpleasant confrontation, the governor confined Captain Dalrymple to barracks under guard. The Board of Trade refused to consider Dalrymple's plea as it concerned military matters, so he broke arrest and left the province in 1762.

During his absence from Fort Johnston Dalrymple seems to have been aboard the Diligence, generally stationed in the mouth of the Cape Fear River (her home port was Plymouth, England). Admiralty orders sent to Dalrymple during this period instructed him to make observations of forests, roads, sands, sea marks, and tides wherever he was. He also was among those to whom copies of His Majesty's orders in council were sent concerning a cruise against smugglers. Occasionally Dalrymple reported to the Admiralty on defense.

Dobbs died in March 1765 and was succeeded by William Tryon who promptly sought permission to name a local man, Robert Howe, to be commander of Fort Johnston. This did not sit well in London as Howe might not always be suitably objective in matters concerning both his native province and England. By early summer 1765 Dalrymple was back in the province and, having been commissioned by the king, he was again commander of Fort Johnston. Tryon seems to have accommodated himself to the situation and, with increasing local resistance to the Stamp Act centered in the Lower Cape Fear, Tryon and Dalrymple got along together. Tryon was aware that Sir Jeffrey Amherst, then governor general of British North America, was acquainted with Dalrymple's "Military Genius" and was said to consider him to be "the best Adjutant in the Army." Surely Tryon was in no position to question Amherst's judgment. Dalrymple obeyed Tryon's orders and cooperated with the commanding officers of ships in the river off the fort during the Stamp Act troubles.

When Tryon called at Fort Johnston in February 1766, he found Captain Dalrymple sick in bed. A few weeks later, however, the captain was able to carry out certain orders of the governor. Nevertheless, Dalrymple died in the fort on 13 July.

John Dalrymple does not appear in the printed genealogies of the family, yet in his will dated 25 Feb. 1743 (exactly three months before his father's death) he describes himself as the second lawful son to Sir John Dalrymple of Cowsland, Baronet of the Kingdom of Scotland. A manuscript family tree in Scotland indicates that the baronet's eldest son died young; his second son and heir, William, was born in 1704. The next child recorded, a daughter, was not born until 1709. Between the two names on the chart there is an X where the name of another child might have appeared. John would have been the second surviving son. It is interesting that John Dalrymple made his will in North Carolina in the same year that his father died in Scotland (did word of his father's illness prompt him to do this?) although he lived for twenty-three more years. One of Dalrymple's enslaved people in North Carolina was named Cowesland. Did the family intentionally drop him from its records?

At some time prior to February 1743 Dalrymple married Martha Watters of New Hanover County, but there is nothing to suggest that they had any children. She survived him and inherited his considerable property, which she bequeathed to her nieces and nephews in her own will of June 1768. The inventory of Captain Dalrymple's estate includes thirteen enslaved people, extensive livestock, a large quantity of furniture, silver, linen, jewelry, books, and musical instruments. The listing of coopers' and turpentine tools suggests that he was engaged in the naval stores industry. In the settlement of his estate, accounts were submitted for nails, hinges, locks, glass, lumber, and other materials clearly intended for a new house; his death, therefore, must have been unexpected.