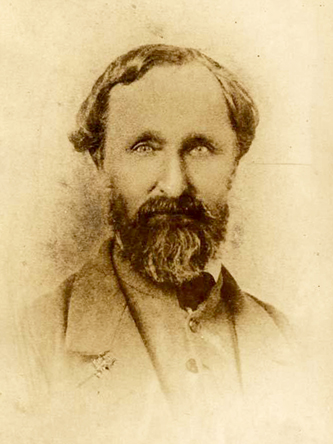

13 Aug. 1812–21 June 1869

James Wallace Cooke, Confederate naval officer and commander of the ironclad C.S.S. Albemarle, was born in Beaufort to Thomas and Esther Cooke. He was orphaned at the age of four years, and he and his sister, Harriet, were reared by their uncle, Henry M. Cooke, collector of customs at the Port of Beaufort. At the age of sixteen, James Cooke was appointed a midshipman in the U.S. Navy; he reported to his first station, the training ship Guerriere, on 1 Apr. 1828. Over the next thirty-three years he had extensive sea duty and service in the naval observatory and commanded the U.S.S. Relief. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant on 25 Feb. 1841.

Upon the secession of Virginia, Cooke resigned his commission in the U.S. Navy on 2 May 1861; two days later he was appointed to the same rank in the state navy of Virginia. His first assignment was with the construction of batteries on the James River. On 11 June 1861 he was appointed a lieutenant in the Confederate Navy and was ordered to duty at the naval batteries on Aquia Creek, which was part of the Potomac River defenses. In the latter part of the summer he was ordered to Norfolk, where he received command of the gunboat C.S.S. Edwards.

The surrender of the forts at Hatteras Inlet on 29 Aug. 1861 curtailed Confederate commerce raiding and threatened the entire eastern portion of the state. As a result of the Confederate military concentration in the area, Cooke was ordered to the command of the gunboat C.S.S. Ellis, which was a unit in Captain William F. Lynch's "mosquito fleet." Cooke took command of the former canal tugboat on 3 Oct. 1861.

When the Union forces attacked Roanoke Island on 7 Feb. 1862, the Confederate gunboats were engaged all day. The Ellis expended all its ammunition as well as that of the disabled Curlew. The Confederate fleet retired the next morning to Elizabeth City for repair and supply. The powerful Union flotilla, commanded by Commander Stephen Rowan, followed closely, and on 10 Feb., after a brief and devastating action at Cobb's Point near Elizabeth City, the Confederate fleet ceased to exist. Although beset by two superior Union vessels, Cooke refused to surrender and with his cutlass met the swarming boarders. After suffering two wounds he was finally overpowered. He received his parole at Roanoke Island on 12 Feb. 1862 and returned to his home in Portsmouth, Va., for recuperation.

Cooke was promoted to the rank of commander on 25 Aug. 1862, to date from 17 May, and following his exchange he was assigned to duty in North Carolina. He was ordered to proceed to Halifax to oversee the construction of an ironclad ram under contract by Gilbert Elliott. Under the resourceful leadership of the two men, the ram was built in a cornfield near Edward's Ferry on the Roanoke River. Constructed of yellow pine and armored with four inches of iron, the vessel was 152 feet in length, 45 feet wide, and drew 8 feet of water. The armament consisted of two 100-pound Brooke rifled cannon mounted in pivot. Christened the C.S.S. Albemarle, the new ship was destined to become one of the most famous and successful of the Confederate ironclads.

By April 1864 the Albemarle was so near completion that the Confederate command proposed a combined army-navy operation against Union-occupied Plymouth, a small port near the mouth of the Roanoke River. Cooke agreed to have the ironclad ready for action, and on the evening of 17 Apr. the vessel began its maiden voyage with portable forges and workmen aboard to fit the final layer of armor. With the aid of high water the Albemarle passed the Union river obstructions above Plymouth, and at 3:30 A.M. On 19 Apr. two Union ships, U.S.S. Miami and U.S.S. Southfield, steamed into view. In minutes the Albemarle rammed and sank the Southfield and drove the battered Miami past Plymouth. All day, shells from the ironclad rained on the Union fortifications, forcing their surrender on 20 Apr. to General Robert F. Hoke. In recognition of the crucial role of the Albemarle in the victory at Plymouth, the Confederate Congress presented a resolution of thanks to Cooke and his crew. Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory wrote, "The signal success of this brilliant naval engagement is due to the admirable skill and courage displayed by Commander Cooke, his officers and men, in handling and fighting his ship against a greatly superior force of men and guns."

The fall of Plymouth threatened the Union position in Eastern North Carolina, and a formidable fleet was gathered in Albemarle Sound to prevent further operations by the Albemarle. In an effort to cooperate with a Confederate move on New Bern, on 5 May 1864 the Albemarle, with two consorts, steamed down to Albemarle Sound to challenge the heavily armed Union fleet commanded by Captain Melancton Smith. For several hours seven of the Union ships engaged the Albemarle in a sustained and fierce battle in which the U.S.S. Sassacus unsuccessfully rammed the ironclad. That evening the lightly damaged Albemarle withdrew, leaving several disabled Union ships. The Albemarle did not attempt another sortie, and the balance of naval power remained stable in the area until 27 Oct. 1864, when Lieutenant William B. Cushing succeeded in sinking the ram Albemarle with a torpedo in one of the most daring acts of the war.

Cooke was promoted to captain on 10 June 1864 for "gallant and meritorious conduct." A week later he was detached from the Albemarle and given command of the inland waters of North Carolina, a post he held until his parole at Raleigh on 12 May 1865. His record in the Confederate Navy established him as one of America's great naval officers. Following the war, Cooke returned to Portsmouth, Va., where he lived in retirement.

In Norfolk, on 5 July 1848, Cooke married Mary E. A. Watts of Portsmouth. The Cookes made their home in Portsmouth and had a family of three sons.