ca. 1700-1780

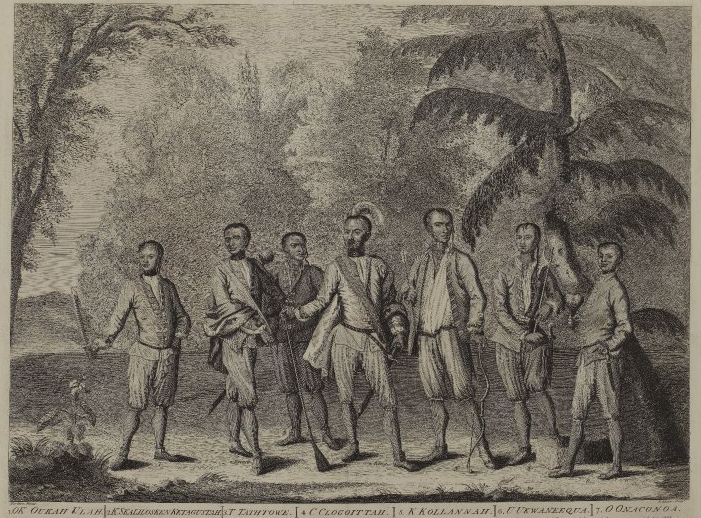

Attakullakulla, a Cherokee diplomat, warrior, and statesman—known to the English as The Little Carpenter, because his name meant "wood leaning up" and therefore suggested house-building—became one of the most prominent Cherokee people of the late eighteenth century. Attakullakulla was born into a high place within Cherokee society. He was destined to high position from youth and on maturity was chosen to the office of second or right-hand man, the executive arm to the first man or priestly Ulustuli of the Overhill Cherokees and hence of the Cherokee nation. His home was at Tuskeegee on the Little Tennessee, a few miles from Chota, the Cherokee capital, in present Monroe County, Tenn. (North Carolina at that time). Attakullakulla first appears in the records at about age thirty, when he was one of six Cherokee ambassadors chosen in 1730 to go to England to make a treaty of trade and alliance. In 1739, he was captured by the Caughnawagas (Canadian Iroquois) and carried to Canada, where he was adopted into the family of the principal Caughnawaga chief. In Canada, he became acquainted with French officers, traders, and priests and met the French governor. Here, he learned and adopted the Iroquois strategy of placing the interests of French against those of the English in order to obtain security and trade concessions. Cherokee security and a plentiful trade were his goals after he returned to the Cherokee country as a result of the 1742 Cherokee peace with the Iroquois.

After 1745, when the Cherokees were at war with the Creek Indians, Attakullakulla was instrumental in bringing Iroquois into the Cherokee country to aid against the Creeks. When, in 1751, because of disturbances attendant upon the Iroquois presence in the Cherokee country, South Carolina embargoed the Cherokee trade, Attakullakulla went to Williamsburg to seek a Virginia trade. Unsuccessful, he went to the Ohio to contact Pennsylvania traders. Governor James Glen of South Carolina then sought to have him apprehended as an enemy. When finally Glen decided to mediate a peace between the Creeks and the Cherokees and to lift the embargo, Attakullakulla, to cement Carolina-Cherokee friendship, led a war party against French convoys on the Mississippi.

In 1753, after Glen had opened official correspondence with the Overhill leadership at Chota, Attakullakulla went as emissary to Charleston and there, with threats of competition from Virginia, Pennsylvania, or even the French, forced Glen to provide better terms in the trade. Nevertheless, mindful of the disastrous embargo of 1751, Attakullakulla determined to undermine the South Carolina trade monopoly. For favoring an effort to open trade with the French, however, his life was threatened by the pro-English headmen of the nation; they forcibly reminded him that, as the only living signer of the Treaty of 1730 with the English, he must hold to the sanctity of his word. Thenceforward, he opposed overtures of any sort to the French but pushed strongly for a Virginia trade.

Fear of Attakullakulla's interest in Virginia led Governor Glen in 1753 to build Fort Prince George at Keowee among the Lower Cherokees. In 1755, the interest of the Virginians in the Cherokees, from whom they desired assistance against the French in the Ohio Valley, brought Glen to Saluda, S.C., in May, where Attakullakulla and Old Hop, the Cherokee first man, obtained trade concessions and the promise of a fort for the Overhill Cherokees, in return for ceding to the British overlordship of the lands all the way to the mouth of the Tennessee River.

Continuing Virginia efforts to obtain Cherokee help and the slowness of South Carolina in implementing Glen's Saluda promises brought Attakullakulla and other Cherokees to Broad River, N.C., to make a treaty for Virginia trade and a Virginia fort among the Overhills. In return, Cherokee warriors would operate against the French on the Virginia frontier. At this time, Attakullakulla and others consented to the building of Fort Dobbs, twenty miles west of Salisbury. Delays in implementing the Broad River treaty led the Overhills to disillusionment with the English and with Attakullakulla's diplomacy. When finally, in late 1756, South Carolina did build Fort Loudoun near Chota, Attakullakulla led Cherokees against the French on the Mississippi. Relatively few Overhills went to Virginia, that frontier being left to the Lower Cherokees to defend.

When in 1758 friction between Cherokee horse stealers and Virginia frontiersmen and scalp hunters caused the death of a score of Cherokees in Virginia, the Cherokees demanded war on the English. Attakullakulla stood for peace and, stalling a declaration of war, went to Virginia to seek Virginia reparation and a Virginia trade. In the latter effort he was successful, but before he could return, Cherokee vengeance seekers had murdered a score of frontiersmen in North Carolina. He still strove for peace. In October 1759 a delegation of Cherokee peacemakers, including Oconostota, the Great Warrior, went to Charlestown, but there they were seized by Governor William Lyttelton as hostages for the surrender of those Cherokees who had murdered North Carolinians. Lyttelton marched a South Carolina army to Fort Prince George to enforce his demands. Attakullakulla conducted negotiations for the Cherokees and managed to free Oconostota and three others by promising to surrender four of the murderers, but the Cherokees refused to honor the promise and went to war against South Carolina. Attakullakulla refused to participate in the war or in the councils of the Cherokee nation and withdrew with his family into the woods. In 1760, when the Overhills captured Fort Loudoun and massacred the officers, Attakullakulla rescued Captain John Stuart, who had befriended him in Charlestown, and sent him off to Virginia. After British armies had twice devastated the Cherokee country, Oconostota called on Attakullakulla to enter into peace negotiations with South Carolina. Attakullakulla effected the peace in December 1761.

Early in 1763 he opposed Creek efforts to involve the Cherokees in war with the English, and he led war parties against the Iroquois, who in 1761 had warred against the Cherokees as allies of the English. He was probably instrumental in the murder of Iroquois deputies who came to broach a peace to avert an all-Indian uprising against the English.

In November 1763, as the agent of Oconostota, he attended the great conference of southern governors with the southern Indians at Augusta, called by John Stuart, then his majesty's superintendent for the southern Indians, to settle trade and boundary problems. Attakullakulla spoke strongly for trade and peace and against white encroachments in the valley of the Kanawha and urged the fixing of boundaries to protect the Indian country from trespass.

In June 1765 he went to Virginia to demand reparation for recent Virginia murders of Cherokee people and to ask for a Virginia trade. The Virginians agreed but were so slow in implementing their promises that Attakullakulla had great difficulty in frustrating Cherokee demands for war. Finally he proposed that war be delayed while he and Oconostota went to England for redress. Stuart rejected this plan but agreed to help the Cherokees obtain peace with the Iroquois and promised a quick survey of the boundary. He sent Attakullakulla and Oconostota to New York to make peace with the Iroquois. From November 1767 until the following April, they were at Johnson Hall in the Mohawk country making the peace.

With the Iroquois war settled, Attakullakulla attempted to make peace with the Wabash River American Indian tribe north of the Ohio, who had been inveterate enemies. After failing to do so, he led a war party against Wabash River tribe to avenge the deaths of relatives.

After 1769, Attakullakulla was associated with land deals that brought white colonists ever nearer the Cherokee country. These were efforts to legitimize the inevitable and thus avoid war. Goods shortages occasioned by repeated colonial nonimportation agreements in the struggle of the colonists with the Crown made the quantities of goods and ammunition received in these deals attractive. The 1769 treaty with James Robertson leased the Watauga lands to North Carolina settlers for eight years.

In October 1770, Attakullakulla attended the conference at Lochaber, S.C., at which the Cherokees ceded the land east of a line from six miles east of the Long Island of the Holston to the mouth of the Kanawha in the Ohio. During the survey he altered the line to extend westward along the east bank of the Kentucky River. The new line violated the treaty of Lochabar, and its generosity has been attributed to the gifts he received. In the autumn of 1774, despite Lord Dartmouth's prohibition on sales west of the Lochabar line, Attakullakulla was engaged in negotiation with Richard Henderson of North Carolina for the sale of all lands between the mountains and the Cumberland River. He went to North Carolina with Henderson to determine the quantity and types of goods to be given the Cherokees for the sale. The Cherokees received $10,000 in goods at the ratification of the sale at the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, 14–17 Mar. 1775. Though the quantity of goods seemed large, when they were distributed among the Cherokees, each man received much less than he could make in a year hunting the same territory. Many Cherokees were dissatisfied, and soon there were clashes with white colonists settled on the Watauga lands and elsewhere. Attakullakulla's influence began to wane. In May and June of 1776, Attakullakulla supported Stuart's efforts to keep the Cherokees from going to war before the British were ready to attack the South, but neither he nor the other elder headmen could prevent the young Cherokee warriors from going to war. Attakullakulla then went to Pensacola to demand that the British supply the Cherokees with a trade.

Retaliation from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia resulted in destruction of most of the Cherokee towns. The rebellious opposition fled to the Chickamauga region of northwest Georgia, where they could maintain contact with the British. Attakullakulla and Oconostota then made peace overtures to the Americans, which resulted in the Treaty of Fort Patrick Henry in April 1777, wherein the chiefs agreed to neutrality in the war between the British and the Americans. This treaty, however, did not prevent the Chickamauga dissidents from continuing the war. Few American traders went to the Cherokee country, and the neutral towns were denied a British trade. In February 1778, Attakullakulla visited Pensacola, where he sought a friendship with the English and applied to Stuart for renewal of trade. Unsuccessful, in September he visited Fort Rutledge in South Carolina on a similar mission and sought friendship for the Americans. The effort failed, and he died shortly afterward.

After 1753, Attakullakulla consistently opposed war with the colonists and the English and sought by every means to increase the flow of trade goods to the Cherokee country. Although he is accused of having taken "bribes" while promoting these policies, to Attakullakulla they were not perceived as bribes. The cultural custom of nearly all eastern American Indian diplomats was to expect presents from opposing negotiators on successful completion of a treaty. The "bribes" that Attakullakulla was described to have accepted were understood by him to be these gifts of negotiation.

Attakullakulla had an English-style frame house at Tuskeegee, and he once asked Governor Glen to give him enslaved people to help his wife. His demand went unfulfilled because of a South Carolina law forbidding ownership of enslaved people by American Indian people. While racially and culturally indigenous, Attakullakulla enjoyed the lifestyle and amenities of white colonists, and sought peace and economic prosperity for his people.