Steamboating in Eastern North Carolina

by Emory W. and Lynn Veach Sadler, 2011.

See also: History of Transportation for K-8 Students

History

The general history of steamboating in North Carolina is rich. When President Monroe visited Wilmington, he was taken to Smithville on a steamboat named Prometheus. Another steamboat, the SS Arapahoe, was the first ship in North America to send an SOS distress message. Not surprising, this event occurred in 1909 off Cape Hatteras, where many ships met trouble.

The general history of steamboating in North Carolina is rich. When President Monroe visited Wilmington, he was taken to Smithville on a steamboat named Prometheus. Another steamboat, the SS Arapahoe, was the first ship in North America to send an SOS distress message. Not surprising, this event occurred in 1909 off Cape Hatteras, where many ships met trouble.

Except for prominent rivers such as the Cape Fear, Black, Northeast, Neuse, and Roanoke, North Carolina’s eastern waterways were shallow, winding creeks and streams frequently impeded and not receptive to the masted ships with deeper drafts common in the early 1800s. Navigable waters often ended at the Fall Line. The town of Cross Creek (now a part of Fayetteville) developed at the point where rapids halted early settlers going up the Cape Fear. Because of such natural impediments, steamboats became important vessels. With their shallow drafts, they were able to travel further inland than masted ships.

Traveling by steamboat was not without its challenges. Even in larger rivers, crewmen might have to attach lines to trees and pull their vessels around sharp bends. Steamers traveling the Cape Fear River met several barriers: Smileys Falls near Dunn in Harnett County and Buckhorn Falls near the junction of Chatham, Harnett and Lee Counties. In optimum conditions, those able to travel past both falls could get as far upstream as Mermaid’s Point, where the Haw and Deep Rivers joined to form the Cape Fear, but few were small enough to travel further. Goods transported on waterways to or from areas further inland where steamboats could not travel had to use smaller boats, such as the dugout canoe, log boat, periauger (larger than a canoe and typically of cypress), flat/pole boat (important on the South River), or raft/bateau trains. Wilmington was a large trading center and getting naval stores, which included lumber, tar and resin, to it was important to early commerce. Salt, commodities, and imports from, for example, New York and the West Indies, had to travel upstream to the state’s interior. Nineteenth-century plantations had their own landings, where steamers were flagged from the shore by day with white handkerchiefs and by night with torches, lanterns, or fires on the bank.

Johnson’s Riverboating in Lower Carolina described over one hundred steamboats. Since its publication (1977), additions have been made to the list. North Carolina Business History names the Sea Horse the earliest (1812) constructed of passenger and freight steamboats working North Carolina waterways. Among the first, too, were the Norfolk, Henrietta and Prometheus. These came eleven years after the first American commercial steamboat, Robert Fulton’s North River, which was mistakenly called the Clermont after the estate of Fulton’s backer. It operated on the Hudson River. A Norfolk merchant brought the Sea Horse down the Roanoke River to North Carolina from Perth Amboy, New Jersey, in 1818 to transport cargo. The New Bern Steamship Co. purchased the Norfolk for the Neuse River. Though built out of state, it saw service before the others. James Seawell was responsible for the first steamboat constructed in-state, the Henrietta, named for his daughter. It traversed the Cape Fear between Fayetteville, his home, and Wilmington and would be the first to go up the Cape Fear to Averasboro. Captain Otway Burns built the Prometheus at Swansboro to travel between Wilmington and Smithville (now Southport). John Stevens, of Hoboken, New Jersey, blocked by a Fulton monopoly in New York, had petitioned the North Carolina State Legislature in 1812 for a twenty-year monopoly to provide steamboat service but failed to meet his commitment. Joseph Seawell held a seven-year monopoly for steam navigation of the Cape Fear between Wilmington and Fayetteville. The Cape Fear Navigation Company, 1816-1838, worked to improve its titular river by removing some 1,159 impediments.

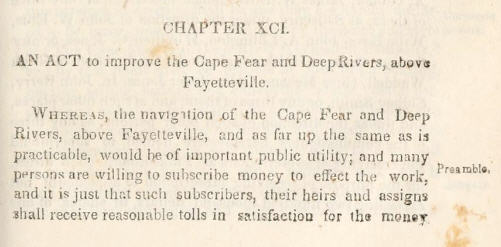

In 1849, the Legislature passed the Cape Fear and Deep River Navigation Acts (Chapters XCI and XCII) to build a series of dams with locks and canals enabling barges and small steamships, limited to twenty feet in width, to run from Lee County to Wilmington. The first trip was made in 1855; in 1859, a flood virtually destroyed the system. With the coming of the Civil War, repairs were halted. Nonetheless, in 1860, the steamboat Enterprise managed to tow a barge to a coal mine in Gulf (Chatham County) via locks on the Cape Fear. On its return, with coal, Captain Amos Perry had a two-gun salute fired at Fayetteville.

In 1849, the Legislature passed the Cape Fear and Deep River Navigation Acts (Chapters XCI and XCII) to build a series of dams with locks and canals enabling barges and small steamships, limited to twenty feet in width, to run from Lee County to Wilmington. The first trip was made in 1855; in 1859, a flood virtually destroyed the system. With the coming of the Civil War, repairs were halted. Nonetheless, in 1860, the steamboat Enterprise managed to tow a barge to a coal mine in Gulf (Chatham County) via locks on the Cape Fear. On its return, with coal, Captain Amos Perry had a two-gun salute fired at Fayetteville.

Steamboat technology advanced, from single- to twin-boilered, side- to stern-wheeler, and wood to iron hull, with flat-bottoms designed for the Cape Fear in low water. The gasoline engine arrived around 1900. Improvement of the waterways began soon after the Revolution, and politicians and businessmen continued to press for the next phase of transportation. Eventually, waterway yielded to railway (though, for a time, railroad cross ties were shipped by water).

Regular steamer service dates from 1856. Construction centered in Fayetteville, Wilmington, and Washington. Companies, shipyards, and some five steamboat lines were established. Among notable steamers prior to the Civil War, the Evergreen had the lightest draft on the Cape Fear. The Rowan, however, drawing fifteen inches, was among the early flat-bottom steamers designed for that river during low water. While freight and mail (later) were primary, passenger service developed more slowly. The Southerner berthed thirty. People enjoyed “excursions” (e.g., on the 4th of July) between Smithville (renamed Southport in 1889) and Wilmington until 1932, and the Henrietta III conducts cruises in Wilmington today. The Flora McDonald, the second iron-clad steamer on the Cape Fear, catered to first-class passengers. After Wilmington fell to Union Forces in February of 1865, towards the end of the Civil War, most of the remaining steamboats headed upriver and were captured when Union forces occupied Fayetteville, but the Flora McDonald went to Elizabethtown. Captain Wynder marched his Confederate company there to prevent enemy gunboats from coming up until General Johnston’s army had cleared Fayetteville and burned the steamboat not only to prevent her capture but to obstruct the waters.

Development along the Black River and other Cape Fear tributaries lagged some fifty years behind those along the Cape Fear because steamboats were too large to navigate them easily and the amount of freight available in Bladen, Brunswick, Duplin, Pender, and Sampson Counties could not support the crews, which numbered up to twenty-five individuals. R. P. Paddison, from Harrells (Sampson County), had served in the Civil War and afterwards opened up the Black and Lower Cape Fear tributaries with the steamer North East. After that war, too, smaller steamers could be built as a result of improved steam power plants.

Development along the Black River and other Cape Fear tributaries lagged some fifty years behind those along the Cape Fear because steamboats were too large to navigate them easily and the amount of freight available in Bladen, Brunswick, Duplin, Pender, and Sampson Counties could not support the crews, which numbered up to twenty-five individuals. R. P. Paddison, from Harrells (Sampson County), had served in the Civil War and afterwards opened up the Black and Lower Cape Fear tributaries with the steamer North East. After that war, too, smaller steamers could be built as a result of improved steam power plants.

The War Between the States took its toll on steamboating but offered some opportunities. In May 1861, North Carolina forbade exporting food and grain beyond its borders, and the blockade affected exports of naval stores and cotton. Transport of troops and war supplies offset the loss of traffic to some extent. The A. P. Hurt took Federal troops from the arsenal in Fayetteville to Wilmington after it surrendered to the Confederacy in 1861. The Reindeer hauled coal from the Deep River mining field to Fayetteville and Wilmington under contract to the Confederacy. The State commandeered the James R. Grist to take workers and supplies to the salt works near Wilmington; they were drafted by the Confederacy in 1863. At the end of the war, few usable steamboats were left on the Cape Fear. New ones had to be built to meet returning demands for cotton and naval stores. R. M. Orrell ran a fleet of steamboats from Fayetteville. Wartime obstructions, including “Yankee catchers” (stone-filled cribs with sharpened iron heads on timbers to impale boats) were removed.

Steamboats had a role in the history of African Americans in North Carolina as well. Dan Buxton and P. D. Robbins were two prominent African Americans in the industry. When Union troops captured the A. P. Hurt at Fayetteville (1865), they named Dan Buxton its pilot and sent it to Chinquapin. Buxton went to the businessmen who had originally owned the A. P. Hurt, told them he still considered her their property, and promised to return her if he were retained as pilot for life. When she sank in 1923, he was still on the job after sixty years and was deemed a master pilot. After moving to Hallsville around 1879, P. D. Robbins sawed timber at his own mill to build the steamboat St. Peter. Robbins was a descendant of a Chowan Indian chief and a sergeant in a Black cavalry unit. He had fought for the North, then returned to Bertie County and represented it at the State Constitutional Convention. Later in the State Legislature, he also served as postmaster of Harrellsville and invented two pieces of farm machinery.

After World War I, steamboating on the Cape Fear largely ended, but the A. P. Hurt, the third built with an iron hull, survived from 1860 to its sinking in 1923. Twice burned, it was rebuilt from that hull and called the C. W. Lyon before reclaiming its original name. Contrastingly, the Thelma was so neglected that it sank where moored in Elizabethtown. North Carolina Historical Marker I-69, in Clear Run on the Black River, mentions the A. J. Johnson, which sank in 1914. Fragments of the hull remain visible at low water.

Steamboating lore

The lore of steamboating, on the other hand, has continued to thrive. It includes stories, mnemonic devices for distinguishing different numbers of “toots,” and real events made more wonderful with each telling. Most were gathered from various sources by F. Roy Johnson.

A favorite tale was the “Stubborn Steer,” who not only could not be removed from his steamer, but lay down on its deck. An African-American drayman made 50¢ (more than a deck hand earned in a day) by turning his cart bottom-up over the animal, lashing him to it, turning it over, and trundling it to the Wilmington slaughter pens.

The steamboat Lisbon came to be known as “Noah’s Ark” when it was seen rescuing humans and animals during an 1891 freshet.

Another tale involved an elderly, well-built African-American man who made his living catfishing and carrying passengers up the steep, muddy bank at Elizabethtown. A beautiful young woman accepted his offer and climbed on his back rather than continue by steamboat the forty miles to Fayetteville and return in a hack. He answered her query of how much she owed with, “There ain’t no charge, Miss. It was wuth it!”

Darkness and foreboding abound in the lore and include the dangers of falling asleep or sleepwalking aboard. The tragedies reverberated, especially scalding deaths of crew members from bursting boilers and drownings when rafts and flat boats overturned in the wakes of steamers. Even holy men could not escape the darker lore; hence the misadventures of Reverend Pearsall. This lay preacher of Duplin County solicited funds to have Luther Sherman build (1938-1939) the last ship of importance on the Black River. Pearsall intended to preach on board and installed play equipment on the deck to keep children amused. At the launching of The Gospel Ship, the chocks refused to be removed and, even when they yielded, the boat would not slide into the water without great effort. When it at length “took the tide” and reached Wilmington, it was not properly tied up, and a rogue wave crashed it into the pilings; one pierced the hull and sent it to the bottom. Another truth-born tale became known as the “Mystery of the Lost Bridegroom Solved.” He disappeared from deck, and, when his skeleton was finally found, it was identified by a marble pyramid he was known to have carried.

Also included in the culture are songs, “hollers and hoots,” whistle tunes and such accoutrements as wooden cracker boxes packed with food for boatmen and quilts to wrap around crew members' heads as they slept fireside. On the most crooked and narrow waters, pilots were said to need “gumberry licenses”—they knew to pull away from the bank when they could hear the gumberries drop. City water was avoided in favor of springs and artesian wells. Deckhands passed large buckets of these preferred waters from bank to boat. In the late nineteenth century, some steamboat wells were drilled at landings along the Cape Fear and Black Rivers. When the steamers blew at night, boys used “literd” (lightwood) torches to light the way for passengers to disembark and freight to be unloaded. Wood choppers stacked cords of wood near landings and left notes on trees with the price. The boatmen wrote down how much they had taken, and steamboat owners were billed accordingly. When wood was taken on board, even the passengers joined the line of crewmen passing it to the boat. Especially fetching are the names of the many river landings and flag stops (e.g., “Pull and Be Damned” on the Black River). The history of steamboating, with all of the attendant trappings, is indeed rich.

Educator Resources:

Grades K-8: https://www.ncpedia.org/transportation-north-carolina-k-8

Image credits:

"Steamboats." Slideshow images from the NC State Archives Flickr account. Online at https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/sets/72157625903639036/.

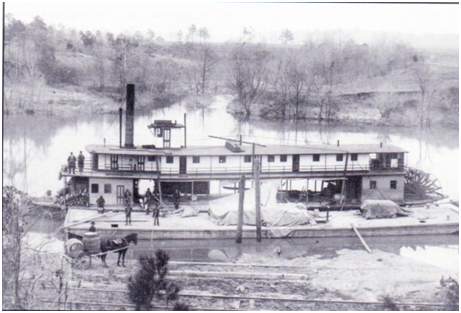

“The river steamer Cape Fear docked at Fayetteville, ca. 1875” in Robert Preston Harriss Papers, Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University.

"Cape Fear River Steamboat." 1905. New Hanover Public Library. Online at http://cdm15169.contentdm.oclc.org/u?/p15169coll4,118.

References and additional resources:

Bridgers, Captain Henry Clark, Jr. Steamboats of the Tar (River) Papers. Manteo, N.C.: Outer Banks History Center. 33MSS99.

Brown, Bonita. Private collection of materials and slides about steamboating in eastern North Carolina. Currie, NC.

Johnson, F. Roy. 1977. Riverboating in Lower Carolina. Murfreesboro, NC: Johnson Publishing Co.

Henderson, Archibald. 1917. Chronicles of the Cape Fear River, 1660-1916. Accessed 01/2011. Online at the Hathi Trust Digital Library at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015062319218.

“Lee County North Carolina Historical Documentation.” No date. Jamestown, NC: The Custom House. Based on the work of Marvin E. Gaster.

North Carolina Digital Collections (Government & Heritage Library and NC State Archives) results on steamboats.

Olson, Christopher. 2006. "The Curlew: The Life and Death of a North Carolina Steamboat." North Carolina Historical Review. April 1, 2006. Accessible online via NC LIVE.

Resources on steamboats and North Carolina in libraries [via WorldCat]

Sprunt, James, 1846-1924. 1895. Tales and traditions of the lower Cape Fear, 1661-1896. Accessed 01/2011. Online at Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/talestraditionso00spr.

"Steamboats in North Carolina. 2006 North Carolina Business History. Accessed 01/2011. Online at https://www.historync.org/steamboats.htm.

"Steamers Digital Exhibit." Joyner Digital Library. East Carolina University. Online at http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/exhibits/steamers/index.html.

15 January 2011 | Sadler, Emory W.; Sadler, Lynn Veach