Four regiments of white North Carolinians served the Union during the Civil War: the 1st and 2nd North Carolina Union Volunteer Infantry in the Coastal Plain and the 2nd and 3rd North Carolina Union Mounted Infantry in the Mountains. The Union also recruited a black brigade in North Carolina, the African Brigade, which consisted of formerly enslaved people.

The 1st North Carolina Union Volunteer Infantry was authorized in May 1862 by Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, whose army had just completed the conquest of the state's Coastal Plain from the Virginia border south to New Bern. The unit's history, however, dates to the original invasion of the Outer Banks in August 1861 by Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler. Small groups of North Carolina Unionists requested protection from Federal army and navy commanders and proclaimed a willingness to serve in the U.S. Army. The primary function of the 1st North Carolina was defensive duty in and around the occupied towns. Its troops acted as pickets, guards, and gun crews in block houses and were especially useful to Union forces as scouts. Their offensive operations were confined to small-scale expeditions into the countryside, generally in the company of northern units. One exception was Company L, designated as cavalry under Capt. George W. Graham, who had transferred from a New York regiment. This unit gained the respect of Federal commanders as well as widespread publicity in the northern press.

The 2nd North Carolina was formed in the last months of 1863 under Capt. Charles H. Foster, a Maine native who had edited a newspaper in Murfreesboro before the war. This unit suffered from poor organization and bad luck, and its misfortunes resulted in a general lack of respect for North Carolina regiments by Federal commanders. The recruits in the second regiment differed markedly from those in the first. Rather than enlisting only patriotic Unionists, this unit also attracted war-weary Confederate deserters and poor men who were tempted by the $300 bonus and care for their families. Within two months, in February 1864, Confederates commanded by Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett captured an entire company during an attack on New Bern.

The western units, the 2nd and 3rd North Carolina Union Mounted Infantry, were organized in October 1863 and June 1864, respectively, and headquartered in Knoxville, Tenn. Enlisting soldiers for these regiments was not difficult. Unionism was strong in the Mountains, where many residents resented the enslaving aristocracy of the eastern planters. This was especially evident in Henderson, Transylvania, Yancey, Madison, Mitchell, and Wilkes Counties. Pro-Union sentiment was so strong in Wilkes that Confederates referred to the county as the "Old United States." A Union company organized in Henderson County in 1863 later became Company F, 2nd North Carolina Mounted Union Volunteer Regiment. Early in the war "underground railroads" secretly guided southern Unionists to northern recruiting stations in Tennessee and elsewhere. These men were joined by numerous North Carolinians who had deserted the southern armies following the devastating Confederate defeats at Vicksburg and Gettysburg.

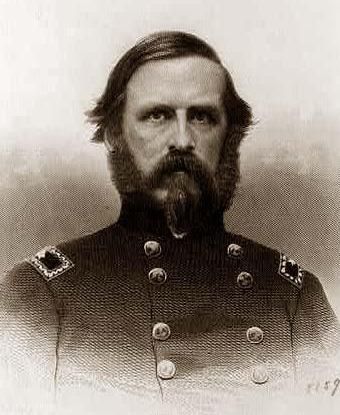

North Carolina's Mountain regiments originated in February 1864 with an order authorizing Maj. George W. Kirk to raise a regiment in eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina. Recruits were enlisted for three years and designated as mounted infantry, using privately owned or captured horses. The first regiment was organized in October 1863 with headquarters at Knoxville, Tenn., and Kirk as regimental commander. The 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry Regiment was formed in Knoxville in June 1864.

The Confederate population of western North Carolina, which feared incursions into the state, considered Kirk's Volunteers, as the regiments were sometimes called, to be outlaws. Two Federal reports lend credence to this view. In March 1864, five months after the first regiment's formation, the Union division commander, Brig. Gen. T. T. Garrard, viewed it as undisciplined and of little value to his organization. Civilized warfare was certainly violated in a January 1865 order issued to the regiment to take no prisoners and shoot guerrillas, Confederate Home Guards, and partisan rangers whenever and wherever found. There were no actual military campaigns in the Mountains until 1865. But the mountain passes were of strategic importance. The 2nd and 3rd North Carolina Union Mounted Infantry thus did not engage in major battles but fought many small skirmishes.

The African Brigade was formed at a time when few Union army or Federal government officials favored black soldiers, although the groundwork had been laid in Massachusetts by the black 54th and 55th Massachusetts Volunteers. Despite official reticence, the Union army employed blacks as spies, scouts, and guides. Many others worked in civilian support roles in army camps in eastern North Carolina. A March 1863 census of the freed black population in New Bern enumerated 8,500 adult males.

Union authorities planned to raise four black infantry regiments from North Carolina, aided by Governor John A. Andrew of Massachusetts and Col. Edward A. Wild of the 35th Massachusetts Volunteers. They looked for white officers committed to abolition and temperance to mix with black officers. Wild chose James Chaplain Beecher, half brother of abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe, to lead the 1st North Carolina Colored Volunteers (NCCV). On 18 May 1863 Wild began recruiting from among the freedmen gathered in New Bern. The first recruits came from more than 30 North Carolina counties. Equipment was often substandard, but by 25 June Wild pronounced the first regiment complete. On 3 July the unit embarked on its first mission, conducting a raid on the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad that considerably alarmed Confederate North Carolina-raising the specter of massed, armed black men. On 30 July Wild and more than 2,000 soldiers of the African Brigade embarked for Charleston, S.C.

After Wild left North Carolina, recruitment for the 2nd NCCV slowed and formation of the 3rd NCCV was delayed. Although the 3rd was eventually formed, a fourth regiment never materialized. An additional heavy artillery regiment was gradually mustered in from freedmen in occupied North Carolina throughout 1864, but early that year the African Brigade had ceased to exist and its soldiers entered the ranks of the U.S. Colored Troops.

Concerns about formerly enslaved people serving voluntarily and white people accepting these men proved to be unfounded. Beyond their legacy of a demonstrated commitment to the Union, members of the African Brigade were, through their handpicked officers, exposed to a core set of abolitionist values that aided their transition to emancipation.