See also: Greensboro Sit-Ins (UNC Press); Sit-Ins During the Civil Rights Movement (NCpedia Student Collection); Greensboro Four

The Greensboro Four

Sit-ins were a peaceful way to fight segregation in businesses and other public places during the civil rights movement. One of the most well-known sit-ins was the February 1960 sit-in in Greensboro. There, a small number of young people altered the course of history by taking a stand, or in this case a seat, to make a big impact. It was not the first sit-in protest in the state, but it caught national attention.

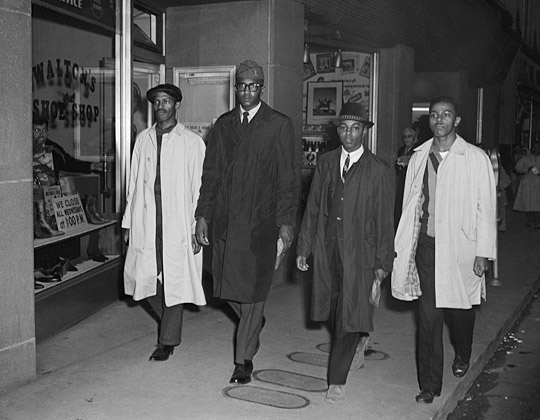

Four Black students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College (NCA&T) organized the Greensboro sit-in. Their names were Ezell A. Blair Jr. (now Jibreel Khazan), David L. Richmond, Franklin E. McCain, and Joseph A. McNeil. They were all freshmen at NC A&T and became known as the “Greensboro Four.”

The Greensboro Four’s sit-in started on February 1, 1960, at the F.W. Woolworth’s Store in downtown Greensboro. The Greensboro Four sat down at Woolworth’s whites-only lunch counter and the staff refused to serve them. Despite being denied service, the protesters remained in their seats.

The Woolworth’s store manager, Clarence Lee “Curly” Harris, went to the police station to ask them to get involved. The police said they could only arrest the protesters if Harris pressed trespassing charges. Harris said he would only press charges if the protesters became violent. Since the protesters remained non-violent, Harris did not press charges and the police did not get involved on this day. Even though there were no police or arrests, the sit-in was big news. Reporters arrived to broadcast the protest on television and take photos for newspapers.

The Greensboro Four stayed in their seats until fifteen minutes after the store closed on February 1.

After February 1

When the Greensboro Four returned to the Woolworth’s counter on February 2, they were joined by more than 25 other students from NCA&T. The sit-ins excited students and attracted more protesters each day. Soon, there were more protesters than seats!

When the protesters returned on February 3, 63 students showed up to protest, including students from nearby Bennett College and Greensboro College. The Woolworth's lunch counter had 65 seats, and almost every seat had a protester sitting in it.

On February 4, the protest outgrew Woolworth’s and students started a second sit-in at the nearby S. H. Kress and Co. store's lunch counter. Like Woolworth’s, it refused service to Black guests in certain parts of the store. The protesters wanted to integrate their store as well. The manager of Woolworth’s offered to integrate, or desegregate, if other stores like Kress did the same, but the others refused.

On February 5, nearly 300 students joined the sit-in at the Woolworth’s counter. This included Black students from Dudley High School and white students from the Woman's College of the University of North Carolina (now UNC Greensboro) and Guilford College.

Even though the protesters remained peaceful, the stores were not. The Woolworth's store could not operate normally because it was so crowded with people. The protesters weren't the only people inside, there were also many counter-protesters who did not want Black people to have equal rights. They insulted, spat on, and yelled at the sit-in protesters. One counter-protester even lit a sit-in protester’s coat on fire. One observer noted that the sit-in protesters tolerated consistent abuse. “They would take things nobody would take.”

On February 6, 1960, someone called in a bomb threat to Woolworth’s. Woolworth’s and nearby stores, including Kress, closed, and the day became known as “Black Saturday.” No bomb was found, but it scared a lot of people. Protesters offered to pause their sit-ins to give everyone time to come together to find a solution. During this pause in protests, Kress and Woolworth’s closed their lunch counters “in the interest of public safety.”

By February 8, there were sit-ins in other North Carolina cities including Winston-Salem and Durham. By February 11, sit-ins were taking place outside of North Carolina. The movement was quickly spreading across the United States.

Negotiations

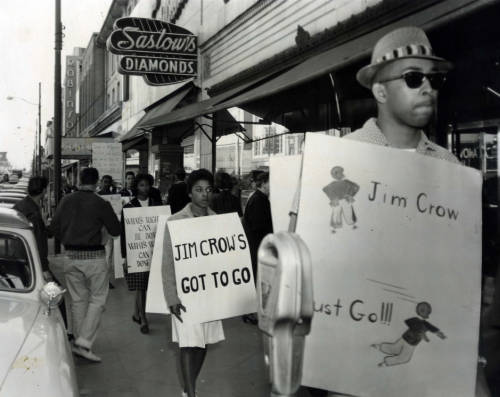

On February 21, the student protesters announced that they wanted to negotiate with the store managers to end lunch counter segregation. Greensboro Mayor George Roach formed the Committee on Community Relations on February 27 to help with the negotiations between the protesters and businesses. Despite the committee's efforts, local businesses would not agree to desegregate the lunch counters. Because business leaders refused to integrate their lunch counters, the sit-ins resumed on April 1 after seven weeks of negotiation. Students began protesting in other ways, including by picketing outside the stores after the stores closed their lunch counters on April 2.

By April 1960, there were student-led sit-ins in more than 70 cities across the South.

In May, the college semester ended, and many of the college protesters returned to their homes away from Greensboro. However, high school students and Greensboro residents continued the sit-ins, pickets, and boycotts, and their protesting led to results. Woolworth’s store sales dropped by fifty percent, and they said they lost $200,000 in sales in 1960 due to boycotts and protests.

By June, the manager of Woolworths was desperate for a solution and feared losing his job. The Woolworth’s office in Atlanta approved lunch counter integration if other stores also began integrating. Kress and another downtown store agreed to desegregate their lunch counters. After more negotiation, an agreement was finally reached on July 20 between protesters and business leaders.

Integration

On July 25, 1960, the lunch counter at the Greensboro Woolworth’s was integrated. The first Black people to be served at the Woolworth's lunch counter were four employees who were invited by the store managers to sit and dine at the counter. Kress integrated their lunch counter the same day. There was no incident or protest. No one called the police, and there were no arrests. The event did not receive much attention from the press. While quiet compared to the protests, the lunch counter integration was a big step for Civil Rights in North Carolina. Protesters had finally achieved what they wanted after six months.

The Woolworth’s store was later converted into the International Civil Rights Center and Museum in 1993, where the original lunch counter is on display. It stands to honor the contributions of Civil Rights activists in the United States, like those who participated in the Greensboro Sit-In.

Glossary:

Sit-in: A peaceful form of protest where people sit in a specific location, such as a restaurant or store, to challenge unfair practices.

Segregation: The legal separation of people based on their identities, such as race or religion, which often leads to unfair treatment.

Civil Rights Movement: A social movement in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s aimed at ending segregation and discrimination against Black Americans and ensuring equal rights for all.

Protest: A way of expressing strong disagreement with something, often to bring about change or raise awareness.

Discrimination: Unfair treatment of a person or group based on characteristics like race, age, or gender.

Integrate/Integration: The process of bringing people of different races or backgrounds together to ensure equal access and rights. Integration and desegregation are synonyms.

Picket: A type of protest where people gather outside of a business or organization and walk in a line, often carrying signs.

Boycott: A type of protest where people stop buying things from a company or as a way to protest the company’s actions or policies.

Read and Reflect Questions:

- Who were the Greensboro Four?

- How did the increasing number of protestors impact the sit-in protests? Provide specific details from the text.

- According to the text, what challenges did the sit-in protesters face?

- What was the impact of the Greensboro sit-ins?

- Were the Greensboro sit-ins successful? Support your answer with details from the text.