Published with permission. For personal educational use and not for further distribution.

7 Jan 1892 - 29 Mar 1972

J.H. Rose was born on January 7, 1892, in Fremont, North Carolina. He married Lenna Elizabeth Arant of Alabama, and they had four children. Rose’s father was a Methodist minister who traveled extensively throughout the state, but J.H. Rose called Warrenton, North Carolina, home. In 1913, J. H. Rose earned his undergraduate degree from Duke University. He obtained a master’s degree from Columbia University in 1926 and also met his wife, Lenna Elizabeth Arant there. He served for two years in the United States Army, Field Artillery, during World War One.

Junius Harris Rose was the Superintendent of Greenville, North Carolina, City Schools from 1920 to 1967. Greenville’s white high school, Greenville High School, was renamed Junius H. Rose High School during his lifetime and first opened for use in 1957.

Rose nearly missed his educational career because he instead considered being a 'railroad man' or an insurance salesman, but in conversation with Dr. E.C. Brooks, who later became State Superintendent of North Carolina Public Schools, a career in education was suggested. This recommendation resulted in “June” Rose taking a job in Kinston, North Carolina, as principal of their high school. Following Kinston High School, Rose went to Bethel High School. Then he volunteered for service in the U.S. Army during World War One. After his stint in the service, Rose returned to Pitt County and was assigned principal of Greenville High School in 1919, where he was principal and also taught algebra and geometry. The next year Rose became Superintendent of Greenville City Schools, a post he held for forty-seven years.

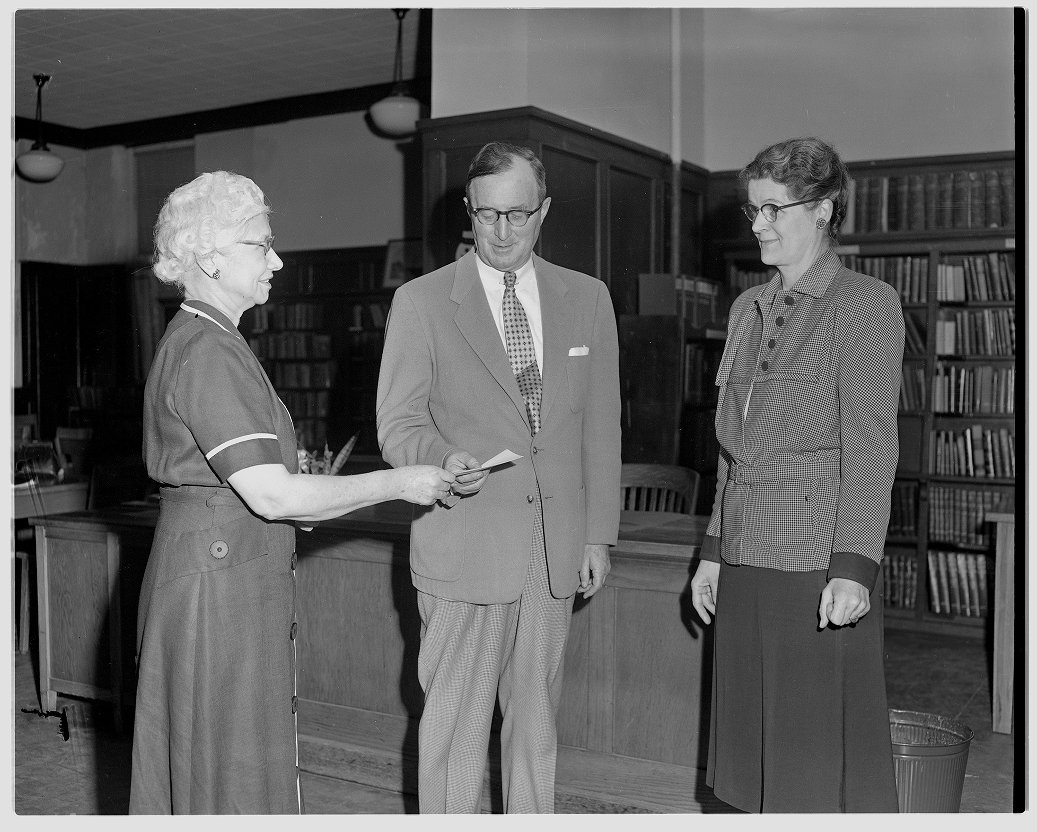

Junius Rose boasted a long story of dedication and service to local, state, and national efforts. He was a prominent member of the education community, serving as the chairman of the legislative committee of the North Carolina Congress of Parents and Teachers as well as the vice chairman of the North Carolina Conference Board of Education. Throughout his career he served on numerous state commissions to study professional school personnel, merit pay for teachers, the needs of public schools, and the feasibility of adding a 12th grade to the North Carolina public school system. He also received the Trustee Award for distinguished service to public libraries for his work with the Sheppard Memorial Library.

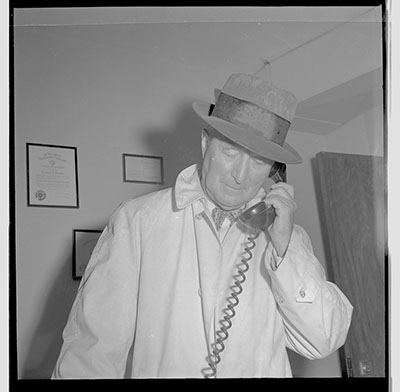

Rose was also passionate about his service to veterans and civil defense. He served as the Assistant State Director of Civil Defense for Eastern North Carolina, the president of the Greenville Housing Commission for veterans, the leader of the Pitt county Confederate Memorial Day ceremonies, and the founder of the first named State Commander of the American Legion. He was especially concerned for the welfare of those with disabilities, serving on the Pitt County chapter of the National Infantile Paralysis Foundation and the NC Commission on Employing the Physically Handicapped. And Rose was among the first to start scouting programs in Greenville and helped lead troops beginning in 1917. He was a rotary club member and participant at Jarvis Memorial Church. In honor of his lifetime of achievements, Rose was given the Golden Deeds Award for distinguished community service.

Rose’s life reflected broader realities in the state and country. His biography chronicled smaller and larger stories that add clarity to the historical record. During World War One, he was mistakenly reported to have been killed in action. When Rose surprised everyone with his miraculous recovery, he appreciated the kind words written about him after his “death.” In the years immediately preceding World War Two, Rose assisted the U.S. Army with implementation of an aircraft warning system for all of Eastern North Carolina, in case of enemy attack.

During World War Two, as the Assistant State Director of Civilian Defense for Eastern North Carolina, Rose evaluated and observed a planned wartime blackout of Wilmington, North Carolina. Rose congratulated students when they volunteered to sell their lone school bus for scrap metal to support the war effort. Afternoon dances at the high school were discontinued because of a wartime shortage of wax and oil needed to keep the floor in good condition. Rose believed that the defense of the nation depended on how hard students worked in school. Everyone should do their part, including female students, Rose maintained. who were needed to run things at home while the men were in the military. He believed that studies in science and home economics would prepare female students for any emergency. Not being assured of an Allied victory in 1943, Rose asked students to register with the U.S. Employment service to volunteer to work on local farms. Superintendent Rose vigorously urged students and the community in Greenville to grow Victory Gardens, purchase War Bonds, and to collect Scrap metal for the war. At the conclusion of World War Two, Rose proudly boasted that Greenville High School graduates were not among draft dodgers through the war years. And during the Cold War, he ensured that supplies for local fallout shelters were organized in case of nuclear attack.

Being prominent in the civic, educational, religious, and social life of the state in the first half of the twentieth century, Rose’s interactions with African Americans in Greenville mirrored many statewide Jim Crow trends. Nevertheless, Superintendent Rose was appreciated, if not loved, by the African American community and was lauded as 'the great white father' who was most responsible for the harmonious and “well-adjusted racial situation in Greenville.” Mrs. Ella Harris, a longtime African American educator in Greenville, knew Mr. Rose as a student and later as a colleague. She recalled that Mr. Rose was a stately man who was kind and who believed that all kids deserved to be educated. Mr. Rose had a history of finding money to get students into college, if they so desired, regardless of race.

Racial harmony was perceived, but a racially divided power structure was present. J.H. Rose’s schedule between May 10, 1933, and May 13, 1933 denoted that reality. On May 10, J.H. Rose was the Master of Ceremonies for the annual Confederate Memorial Day ceremonies, as he had done since 1920. The holiday honored Confederate soldiers and included participation of the white students and use of the white high school’s facilities. Three days later, Superintendent Rose presided over the closing ceremonies of the city’s Colored Schools. J.H. Rose was the nexus between the colored and white communities. Rose had a friend in maintaining racial harmony in Charles Montgomery Eppes, the Supervisor and Principal of Greenville’s Colored Schools. They had worked together to maintain the racial status quo in the city for decades. The dynamic of the relationship was publicly manifested during the Great Depression: In October of 1933, Rose attended “The Good Will Commencement of the high school for Negroes in the city” where tributes were paid to white leaders, including the Mayor, several prominent citizens, and J.H. Rose who were dispensers of relief aid for the Federal Government. Eppes had conceived of the idea in order for “Greenville Negroes to make public expression of their appreciation of the white citizens for acts of kindness to the Negro citizens by these representatives.” And similar to Eppes, Rose was criticized by members of his own race. Rose’s son recalled in an interview that in the early 1940s the Ku Klux Klan left a cross in the Rose family's yard.

During J.H. Rose’s tenure as Superintendent, the 1954 landmark case Brown v. Board of Education had deemed racially segregated public schools illegal. Under Rose, Greenville City Schools, though, did not fully desegregate until after he retired. There were half steps that occurred towards desegregation under Rose, however. In the 1964-1965 school year, two African American students transferred from the Colored C.M. Eppes High School to the white J.H. Rose High School. One of these students, Michael Garrett, characterized his entry into the white school as “token integration.”

When J.H. Rose retired in 1967, two separate and unequal school systems remained: one black and one white. Examples of disparities based on race in Greenville’s Jim Crow Era schools were many, but teacher pay records for the Greenville Schools showed how inequality diminished over Rose’s time as Superintendent. In 1920-1921, the monthly pay for Colored Greenville City Schools’ teachers was 60% of what white Greenville teachers had earned; but by 1942, Greenville Colored teachers earned 79% of what white teachers earned. And Eppes himself, as a principal and teacher, with forty-two years’ experience, was paid less than a first year white teacher in 1920. When Eppes died in 1942, he earned 188% of what a first year white teacher was paid. There was inequality, but there was also measurable improvement that continued until Rose’s final year as Superintendent.

Michael Garrett’s entry into the all-white world of J.H. Rose High School in 1964 was a half-step start that later resulted in the larger strides towards full-integration that happened in 1969-1970, two years after Rose’s retirement. Garret maintained that “Mr. Rose and the rest knew about inequalities between the two schools; how couldn’t he? Rose was in and out of all the schools.” Garrett mused that Mr. Rose was “not a monster or anything. He was operating in a culture that required and expected things to be done in a certain way.” From Michael Garrett’s estimation, many whites and blacks understood, accepted, and lived according to the Jim Crow system.

Junius Harris Rose died March 29, 1972, at age 80.