See also: The Regulator Movement on NCPedia, The Regulators Chapter on ANCHOR

Introduction

The Revolutionary War was not the first time that colonists in the Americas fought against Great Britain. Colonists tried to change the government in the colonies we now know as the United States before the War for Independence. One of these rebellions even took place in North Carolina! The Regulator Movement in North Carolina was an important event that illustrated there were problems between colonists and the government that led to revolution.

When the land of North Carolina was colonized by Great Britain, many of the towns and settlements were founded along the coast. Cities like New Bern sprang up where people arrived. Colonists wanted more land to live on and farm as the population in the Carolina colony grew. They expanded westward and founded new counties (like Orange County) in the western and central parts of the state. Colonists that settled in these western counties, also called backcountry counties, paid taxes and reported to New Bern when they had fees to pay or other legal business.

Backcountry colonists paid taxes but had very little say in colonial government. Their local government officials were chosen by Royal Governor William Tryon in New Bern. Local officers like Edmund Fanning were often dishonest and charged the colonists high legal fees and fines. These fines were often made up and existed simply to make the officers and the governor rich. Royal Governor Tryon also ignored colonists’ requests and tried to enforce unpopular laws in the colony, like the Navigation Acts.

Tryon's Palace and Rebellion

In 1766, the North Carolina colonial legislature gave permission and money for a “Government House” or capital to be built in New Bern. The building would be Tryon’s home as well as a government building where the colonial assembly could meet. Tryon was not satisfied with the amount of money that the colonial legislature had approved, and he convinced the legislature to increase taxes to raise money for the building. This upset many colonists because it was another example of the colonial government taking money from them to pay for government officials to live a life of wealth. Tryon Palace was completed in 1770 and cost about $3.3 million by today's standards.

Backcountry colonists organized to try to convince Tryon to ease the taxes, fees, and unpopular laws. A Quaker farmer named Herman Husband became a popular speaker for what became known as the Regulator Movement. He encouraged nonviolent protest and asked Tryon to stop charging colonists with high fees and taxes. Husband published pamphlets to let others know that what Tryon was doing was wrong and harmful to backcountry farmers. Tryon ignored the farmers’ requests.

Supporters of the Regulator Movement refused to pay taxes or excessive legal fees until Tryon and the royal government changed. These supporters, also called “Regulators,” hoped to “regulate” Tryon and the government’s behavior. They protested by disrupting local courts and harassing local government officials. By September 1768, the backcountry was in rebellion from the royal government.

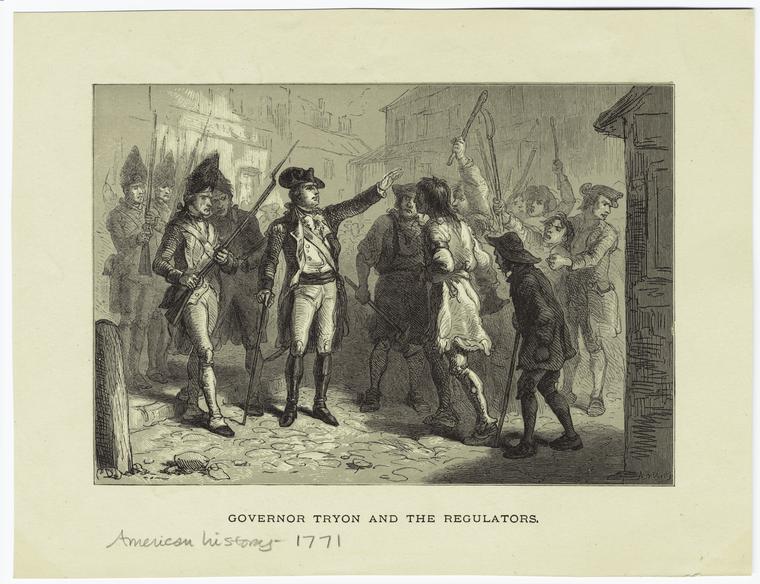

Tryon wanted to stop the rebellion, so he assembled the colonial militia. They helped Tryon keep the Regulator Movement quiet. Husband and another prominent Regulator, John Pryor, were even elected to the colonial assembly in 1769 to try to help solve backcountry problems. Husband tried to present petitions from the backcountry to the other legislators while he was part of the assembly. They explained how backcountry officials were dishonest and asked that collection of public money like taxes be properly recorded. Husband was kicked out of the assembly for “libel,” or writing lies about someone else, even though he was telling the truth. Tryon continued to ignore concerns and issues from the Regulator Movement until September 1770.

The Battle of Alamance and Aftermath

In 1770, in Hillsborough, Crown Attorney Edmund Fanning was beaten and pushed out of town. His house was destroyed by the Regulators. To the Regulators, Edmund Fanning represented many of the problems experienced by people in the backcountry, like high legal fees and government dishonesty. This attack made Tryon take the Regulator Movement much more seriously.

On May 16, 1771, Tryon sent his force of 1,000 militia men led by General Hugh Waddell to Alamance, an area near modern-day Burlington. When they met with the volunteer Regulator force of about 2,000 colonists, the Regulators were ordered to give up their guns, go home, give up their leaders, and follow the crown's rules. They refused. The colonial militia fired on them and started the Battle of Alamance.

At the Battle of Alamance, the Regulators were no match for the colonial militia. They did not have the leadership, proper weapons, or organization that the militia had. For example, Regulator volunteers captured an abandoned militia cannon during the battle. They had no ammo for the cannon, did not know how to use it, and were forced to abandon it. This disorder was common for the Regulators during the battle. Both the regulators and militia had soldiers killed and wounded during the Battle of Alamance. Fifteen of the Regulators were taken prisoner from the battle. After the battle, seven of these fifteen prisoners were hanged for participating in the rebellion.

The Regulators were no more. Tryon offered pardons to those from the Regulator Movement who swore an oath of loyalty to the royal government to help restore order. The Regulator Movement was important even though there was only one battle. It showed that backcountry farmers could challenge the royal government. It also showed that their needs and demands were serious and should not be ignored. These ideas would be an important part of the American Revolution that would come only a few years later.