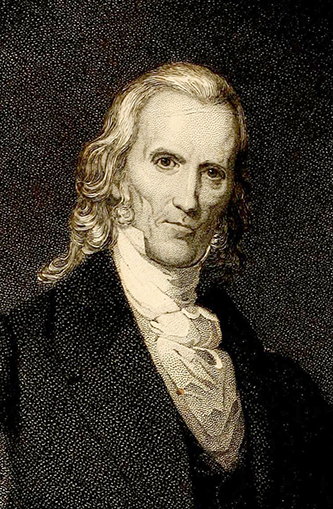

White, Hugh Lawson

30 Oct. 1773–10 Apr. 1840

Hugh Lawson White, lawyer, banker, judge, legislator, claims commissioner, U.S. senator, and presidential candidate, was born to James and Mary Lawson White in that part of Rowan County that is now Iredell County. About 1785 James White moved his family to the Holston River and led in founding Knoxville, Tenn. His service to the state of Franklin—in the territorial legislature, Tennessee Constitutional Convention, and state legislature—and his friendship with the Blounts, John Sevier, and Andrew Jackson connected the family closely to the fortunes of the young state and its pioneer leaders.

Hugh Lawson White, lawyer, banker, judge, legislator, claims commissioner, U.S. senator, and presidential candidate, was born to James and Mary Lawson White in that part of Rowan County that is now Iredell County. About 1785 James White moved his family to the Holston River and led in founding Knoxville, Tenn. His service to the state of Franklin—in the territorial legislature, Tennessee Constitutional Convention, and state legislature—and his friendship with the Blounts, John Sevier, and Andrew Jackson connected the family closely to the fortunes of the young state and its pioneer leaders.

Hugh studied with the Reverend Samuel Carrick, the Presbyterian minister in Knoxville, and read law with Archibald Roane, who was later governor. For a time he served as secretary to William Blount, the territorial governor, and as clerk of the Knox County Court. In 1793 he participated in a campaign against the Cherokee. He spent about eighteen months in Pennsylvania, studying mathematics in Philadelphia and reading law in Lancaster. In 1796 White returned to Knoxville and began to practice law just as Tennessee became a state.

In 1798 he married Elizabeth Moore Carrick, the daughter of his teacher. They had twelve children; two died in infancy, and the mother and eight of the children died of tuberculosis within six years (1826–31). Only two children were living when he succumbed to the disease in 1840. He had married Mrs. Ann E. Peyton of Washington, D.C., on 30 Nov. 1832.

In a period of flamboyant orators, White made his reputation as a careful, scholarly lawyer dealing with the complexities of land law on the expanding frontier. At age twenty-eight he was elected to Tennessee's highest court, the Superior Court of Law and Equity. He resigned in 1807 to enter the state senate, where he supported revision of the land law and creation of a supreme court. He served as a judge on the Tennessee Supreme Court from 1809 until 1815. To most Tennesseans, he continued to be "Judge White," no matter what office he held.

White had become president of a state bank in Knoxville in 1811 and operated it until 1827. He declined to accept any salary from the bank while holding public office—an unusual attitude at that time. After Congress chartered the second Bank of the United States in 1816, White returned to the state senate and worked to secure both an expansion of state banks and heavy taxation on branches of nonstate banks. He also supported legislation to prevent duelers from holding public office.

President James Monroe appointed White to a commission to determine the validity and amounts of claims against Spain that the United States had assumed in the treaty acquiring East Florida. This service revealed White's judicial talents to numerous national leaders. It also allowed him to judge national leaders, and he resented the intervention of Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to secure reversal of a commission policy.

Not only did White disagree with the positions of Adams, but he also agreed with those of Andrew Jackson and supported him on principle as well as from friendship. When Jackson was a candidate for the U.S. Senate in 1823, White supported him, and when Jackson resigned the seat in October 1825, the legislature chose White unanimously. Senator White promptly joined the attack on the Adams administration. He opposed the Clay-Adams plan for U.S. participation in the Pan-American congress in Panama, federal funds for internal improvements in the states, and the protective tariff. White's experience led him to support additional federal judges for the West even though Adams could appoint the judges. Although perfectly consistent with his principles, White's senatorial service supported Jackson's presidential campaigns effectively.

When Jackson became president in 1829, Senator White endorsed every major measure despite his possible disappointment at Jackson's failure to name him secretary of war and despite his growing skepticism of the "Kitchen Cabinet." White was elected president pro tem of the Senate on 3 Dec. 1832, and Vice-President John C. Calhoun's resignation put White in a vital position during the Nullification crisis.

White chaired the committee on Indian affairs in the Senate from 1829 to 1840 and appeared to be the principal architect of the plans for moving the Indians west of the line of white settlement. When the bill to recharter the bank was before the Senate in 1832, White opposed it in a speech that made many of the points later incorporated in Jackson's veto, especially the issue of constitutionality. Jackson sought White's advice on removing the government's deposits but removed them against his advice. Nevertheless, White opposed the resolution that passed censuring Jackson for the action. White was a strict constructionist, but he supported the force bill to collect the tariff in South Carolina and the compromise tariff to ease the dispute.

The long and genuine friendship between Jackson and White broke over Jackson's determination to make Martin Van Buren his successor. When a movement to nominate White began in late 1833, the senator discouraged it. Continued urging, his skepticism of Van Buren, and reports of Jackson's threats to humiliate him led White to make the race. In December 1834 a majority of the Tennessee delegation in Congress asked if White would run if nominated. Tennessee was not officially represented when the Democratic convention nominated Martin Van Buren early in 1835, and many declined to consider the nomination legitimate. When the 1835 elections were held, supporters of White won the governor's seat and legislative majorities. Then the legislature reelected White and nominated him for the presidency.

Because White, Daniel Webster, William Henry Harrison, and Willie P. Mangum shared the opposition vote, White only carried Tennessee and Georgia for 26 electoral votes. In Tennessee White received 36,000 votes to Van Buren's 26,000.

When the election was over, he returned to the U.S. Senate and served until 1840. His most vigorous fight was a futile one to prevent the Senate from "expunging" the resolution censuring Jackson for removing the bank deposits. When the Democrats regained control of the state in 1839, they made plans to get rid of White. The legislature passed six resolutions "instructing" the Tennessee senators how to vote. When the Sub-Treasury bill came to a vote on 13 Jan. 1840, White resigned rather than follow the instructions and vote for it.

He returned home as something of a martyr and died soon afterwards. He was buried in the cemetery of the Knoxville Presbyterian Church, but his influence survived. His treatment by the Democratic party probably had something to do with its failure to carry Tennessee in a presidential campaign again until 1856—even when Tennessee's own James K. Polk was elected in 1844.

In an era of aggressive, colorful leaders, Judge White was a quiet, thoughtful public servant. Surely he had faults, but a man who stood by his principles so honestly and served so disinterestedly deserved more gratitude and remembrance than was the lot of Hugh Lawson White.

References:

DAB, vol. 10 (1936).

L. Paul Gresham, "The Public Career of Hugh Lawson White" (diss., Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., 1943), "The Public Career of Hugh Lawson White," Tennessee Historical Quarterly 3 (1944), "Hugh Lawson White as a Tennessee Politician and Banker, 1807–1827," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications 18 (1946), and "Hugh Lawson White: Frontiersman, Lawyer, and Judge," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications 19 (1947).

Ernest Hooper, "The Presidential Election of 1836 in Tennessee" (thesis, University of North Carolina, 1949).

Robert M. McBride and Dan M. Robinson, Biographical Directory of the Tennessee General Assembly, vol. 1 (1975).

Powell Moore, "The Revolt against Jackson in Tennessee, 1835–1836," Journal of Southern History 2 (1936).

Nancy N. Scott, ed., A Memoir of Hugh Lawson White (1856).

Hugh Lawson White Papers (McClung Collection, Lawson McGhee Library [Knoxville Public Library], Knoxville, Tenn.).

Additional Resources:

Atkins, Jonathan M. "Hugh Lawson White." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=1497 (accessed June 13, 2013).

"White, Hugh Lawson, (1773 - 1840)." Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Washington, D.C.: The Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=W000376 (accessed June 13, 2013).

Atkins, Jonathan M. "The Presidential Candidacy of Hugh Lawson White in Tennessee, 1832-1836." The Journal of Southern History 58, no. 1 (February 1992). 27-56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2210474 (accessed June 13, 2013).

Hunter, C. L. "Hugh Lawson White." Sketches of western North Carolina, historical and biographical: illustrating principally the Revolutionary period of Mecklenburg, Rowan, Lincoln, and adjoining counties, accompanied with miscellaneous information, much of it never before published. Raleigh, N.C.: The Raleigh News Steam Job Print. 1877. 202-204. https://archive.org/stream/sketchesofwester00hunt#page/202/mode/2up (accessed June 13, 2013).

Image Credits:

Welch, T.B. "Hugh Lawson White." North Carolina University Magazine 10, no. 8 (April 1861). Frontispiece. https://archive.org/stream/northcarolinauni18601861#page/n495/mode/2up (accessed June 13, 2013).

1 January 1996 | Hooper, Ernest