Swann, Samuel

31 Oct. 1704–February or March 1774

Samuel Swann, speaker of the Assembly, was the son of Samuel Swann (11 May 1653–14 Sept. 1707) and his second wife, Elizabeth Lillington Fendall (b. 17 June 1679). He was born at his father's plantation in Perquimans Precinct. Swann's father, one of the wealthiest men in the colony, had long served on the Council and held other high offices; he was the son of Thomas Swann, of Virginia, who had served for many years on the Virginia Council. The young Swann's mother, Elizabeth, was the widow of John Fendall and the daughter of Alexander Lillington and his second wife, Elizabeth Cook. Lillington, an early North Carolina settler, was an influential leader and an Assembly member.

Samuel Swann, speaker of the Assembly, was the son of Samuel Swann (11 May 1653–14 Sept. 1707) and his second wife, Elizabeth Lillington Fendall (b. 17 June 1679). He was born at his father's plantation in Perquimans Precinct. Swann's father, one of the wealthiest men in the colony, had long served on the Council and held other high offices; he was the son of Thomas Swann, of Virginia, who had served for many years on the Virginia Council. The young Swann's mother, Elizabeth, was the widow of John Fendall and the daughter of Alexander Lillington and his second wife, Elizabeth Cook. Lillington, an early North Carolina settler, was an influential leader and an Assembly member.

Samuel was one of four children born of his father's second marriage. He had two sisters, Elizabeth and Sarah, and a brother, John. He also had four half brothers, born of his father's first marriage: William, Sampson, Henry, and Thomas. A fifth half brother, Samuel, Jr., had died in 1702. The young Samuel, therefore, was the namesake of his deceased brother as well as his father.

When Samuel was about three years old, his father died. His mother married Alexander Goodlatt but was soon widowed again, for Goodlatt died about 1713. She later married Maurice Moore, who had recently come to the colony from South Carolina. In the early 1720s Moore and Elizabeth moved to the Cape Fear region, which Moore was greatly interested in developing. Samuel remained in Perquimans for some years, probably living at the family plantation, which under his father's will was to go to him at his mother's death.

Samuel's childhood and youth are said to have been spent under the guidance of the closely knit Lillington family, which included several leading politicians. In addition to his stepfather, Maurice Moore, who rapidly gained political influence in the colony, Swann was associated with John Lillington, his uncle; Edward Moseley and John Porter, his uncles-in-law; and John Baptista Ashe, his sister Elizabeth's husband. Moreover, his half brothers were men of wealth and prominence. Both William and Thomas Swann became members of the Assembly, and each served as speaker. From his relatives and members of their social circle Samuel no doubt absorbed an understanding of practical politics that helped direct him to a political career and contributed to his success in that career. His more formal studies gave him an excellent education in law. He also received training in practical surveying.

Swann entered public life in 1725, when he became a member of the lower house of the Assembly. He seems to have served in that body with little or no interruption for the next thirty-seven years. In the early portion of that period he represented Perquimans Precinct, but in 1739 and thereafter he represented the recently formed Onslow County. In March 1742/43 he was elected speaker of the Assembly. With the exception of the years 1754–1756, he continued in that post until 1762, when he declined to accept reelection because of his health.

In 1728 Swann put his training as a surveyor to good use, for that year he was employed as surveyor by the commission that located the boundary line between North Carolina and Virginia. He was on the surveying party that ran the line through the Dismal Swamp, which, it is said, had not previously been crossed by white men.

In February or March 1738/39 the Assembly appointed Swann to a commission charged with revising the laws of the colony, which had last been codified in 1715. Swann's brother John and his uncle-in-law Edward Moseley also were on the commission. Samuel, who was chairman, is said to have been the moving force in preparing the revision, which became generally known as Swann's Revisal. Published in 1752, it was the first book printed in North Carolina.

As speaker, Swann led the lower house of the Assembly during a period of nearly constant struggle against the governor and at times against London officials as well. At issue, in the colonists' view, were what the colonists considered their ancient rights and privileges, the constitution of the colony, and the principles of representative government. In the view of the respective governors, however, the point at issue was the establishment and preservation of the royal prerogative. Although the struggle was marked at times by compromise or even defeat for the colonists, the long-run advantage was with the Assembly, which secured control over fiscal affairs and other crucial matters. Swann's skillful leadership as speaker greatly enhanced the office, raising it to a stature that some considered equal to that of governor.

About 1727 Swann married  Jane Jones, the eldest daughter of Frederick Jones, a former chief justice of the colony (1718–22), and his wife Jane. About 1731 he moved his family to the Cape Fear region, to which a number of his relatives had moved. He settled on a plantation called The Oaks, not far from his brother John's plantation, which was called Swann's Point. Also nearby was Maurice Moore's plantation, located at Rocky Point. Later, when Anglican parishes were organized in the area, Swann became a communicant of St. James Parish in Wilmington.

Jane Jones, the eldest daughter of Frederick Jones, a former chief justice of the colony (1718–22), and his wife Jane. About 1731 he moved his family to the Cape Fear region, to which a number of his relatives had moved. He settled on a plantation called The Oaks, not far from his brother John's plantation, which was called Swann's Point. Also nearby was Maurice Moore's plantation, located at Rocky Point. Later, when Anglican parishes were organized in the area, Swann became a communicant of St. James Parish in Wilmington.

Swann no doubt cultivated the plantation on which he lived and perhaps other land that he owned. He also practiced law and, like his stepfather and other relatives, speculated in land on a large scale. He became very wealthy. His home, The Oaks, was said to be the finest in the Cape Fear area. After his retirement from the Assembly, he devoted himself chiefly to his law practice. He died in 1774 between the last day of January, when he made a codicil to his will, and the seventh of April, when the will and codicil were proved. He was survived by his wife Jane, a daughter, Jane, and a son, Samuel.

Swann's daughter Jane (15 Oct. 1740–1801) married her cousin, Frederick Jones of Virginia, who was the son of Thomas Jones of that colony and the nephew of Chief Justice Frederick Jones of North Carolina. She and her husband had one son, John Swann, and five daughters: Elizabeth, Jane, Rebecca, Lucy, and Ann. When he reached maturity, John Swann Jones took Swann as his surname, becoming John Jones Swann, in deference to the wishes of his grandfather's brother, John Swann, who died childless.

Swann's son Samuel (19 June 1747–11 July 1787) married Mildred Lyon, the daughter of John Lyon, a merchant of Wilmington. He was a major in the minute men organized in the New Hanover district in 1775. Killed in a duel, he was survived by his wife, Mildred, and by three children: Elizabeth, Samuel, and Jane.

References:

John L. Cheney, Jr., ed., North Carolina Government, 1585–1974 (1975).

R. D. W. Connor, History of North Carolina: The Colonial and Revolutionary Periods, 1584–1783 (1919).

Thomas Frederick Davis, comp., A Genealogical Record of the Davis, Swann, and Cabell Families of North Carolina and Virginia (1934).

Lewis Hampton Jones, comp., Captain Roger Jones of London and Virginia . . . (1891).

E. Lawrence Lee, The Lower Cape Fear in Colonial Days (1965).

New Hanover County Wills (microfilm, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh).

William L. Saunders, ed., Colonial Records of North Carolina, vols. 1–6, 9 (1886–90).

James Sprunt, Chronicles of the Cape Fear River, 1660–1916 (1916).

Alexander M. Walker, ed., Abstracts of New Hanover County Court Minutes, 1738–1769 (1958).

Additional Resources:

"Samuel Swann." N.C. Highway Historical Marker D-52, N.C. Office of Archives & History. https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=D-52 (accessed August 5, 2013).

"CSR Documents by Swann, Samuel, 1704-1774." Colonial and State Records of North Carolina. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/creators/csr10230 (accessed August 5, 2013).

"Samuel Swann's Marriage to Elizabeth Fendall." Tyler's Quarterly Historical and Genealogical Magazine 3, no.1 (July 1921). 68. http://books.google.com/books?id=HDMyAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA68#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed August 5, 2013).

Image Credits:

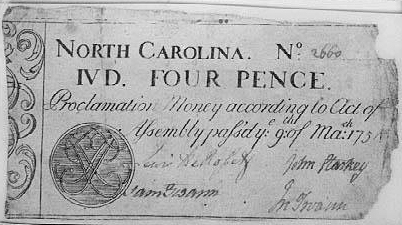

"Money, Paper, Accession #: H.19XX.332.34, E." 1754-1756. North Carolina Museum of History.

"Portrait Miniature, Accession #: H.1979.7.2." 1750. North Carolina Museum of History.

1 January 1994 | Parker, Mattie E. E.