The USS Monitor, lying in 230 feet of water off Cape Hatteras, is probably the most famous victim of the infamous "Graveyard of the Atlantic" off the North Carolina coast. The Monitor was the third Union ironclad approved for construction during the Civil War and the first to be completed for the Union navy. The two previously contracted ironclads were comparable to the growing number of European ironclads. Swedish designer John Ericsson's Monitor, however, was unlike any previous warship. The Monitor was a 776-ton vessel measuring 172 feet long and 41 feet in beam. The freeboard of the ship was just over 1 foot, so even in a light sea its deck was awash. The ship was well protected, with the entire upper portion of its hull encased in iron armor. Amidships, a short cylindrical tower 20 feet in diameter housed the Monitor's two guns. Steam power enabled the turret to rotate 360°, allowing the guns to be trained in any direction without maneuvering the ship. The wall of the turret was 8 inches thick, composed of 8 layers of 1-inch-thick iron plate. Designed by Rear Adm. John Dahlgren, the guns were 11-inch smoothbores.

On 6 Mar. 1862 the Monitor left New York Harbor for Hampton Roads, Va., towed by the tug Seth Low and accompanied by two escort ships. There, the new Rebel ironclad Virginia (converted from the old USS Merrimack) was expected to make its first appearance in a strike at Union blockaders. The trip to Hampton Roads became dangerous for the Monitor when, on 7 March, it encountered a squall that sent waves crashing through air vents on the deck and over the smokestack, nearly drowning the boiler fires. Only fair weather the next day saved the ship from foundering. That night the Monitor steamed into Hampton Roads, only to find a Union naval disaster.

The CSS Virginia had left Norfolk on 8 March to meet the Federal fleet. The wooden Union ships were thoroughly outmatched. The armored Virginia had rammed and sunk the USS Cumberland and destroyed the USS Congress with gunfire. The USS Minnesota, only lightly damaged, had run hard aground during the battle and would be helpless if the Virginia returned. Capt. John Worden anchored his Monitor near the Minnesota to protect it and awaited the reappearance of the Confederate ironclad.

Early on 9 Mar. 1862 the 270-foot, well-armed Virginia approached the still-stranded Minnesota and the strange-looking ship guarding it. At first the Virginia ignored the new Union vessel, concentrating fire on the Minnesota, but then the Monitor opened fire with its two big guns. For several hours the two ironclads pounded each other. The more maneuverable and lighter draft Monitor circled its opponent, constantly rotating the turret to protect the guns except when ready to fire-thus managing to withstand intense enemy shelling. Conversely, the Monitor failed to damage the Virginia. Eventually the two ships broke off the fight, each believing the other had withdrawn first.

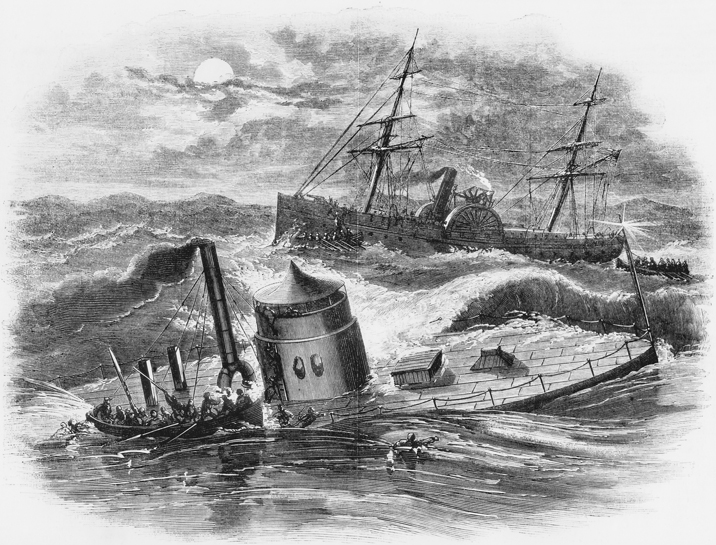

Two months later, Confederate forces abandoned Norfolk and scuttled the Virginia, which enabled the Union fleet to operate up the York and James Rivers. In mid-May the Monitor participated in its final engagement, battling southern shore defenses at Drewry's Bluff. In the fall of 1862 it was overhauled in Washington and at the end of December headed south to participate in an attack on the defenses of Charleston, S.C. Under tow by the USS Rhode Island, the two vessels ran into foul weather off Cape Hatteras. The stormy seas proved too much for the ironclad, as rushing water eventually drowned the boiler fires and cut off power to the engines and pumps. The Rhode Island was able to rescue many of the sailors, but on 31 Dec. 1862 the Monitor sank, taking 16 of its crew to the bottom of the sea.

In August 1973 an expedition sponsored by the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society located the remains of the Monitor, whose identification was confirmed in May 1974. On 30 Jan. 1975 the site became the nation's first National Marine Sanctuary, to be administered by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Monitor was in an advanced state of deterioration, and NOAA instituted a stabilization and recovery program for the wreck. In August 2002 the Monitor's 235-ton gun turret was recovered and installed at the Mariners' Museum in a conservation tank on full public display. It joined hundreds of other Monitor artifacts, including the steam engine, propeller, condenser, propeller shaft, and engine room floor. But the hull of the vessel remains upside down 16 miles southeast of Cape Hatteras.