See also: Live-at-Home Program (Encyclopedia of North Carolina)

The Live-at-Home program was a state-wide agricultural initiative that North Carolina Governor O. Max Gardner inaugurated upon taking office in 1929. Striving to combat rural poverty during a major agricultural recession and the largest economic crisis in the nation’s history, Gardner called on North Carolina farmers to help themselves.

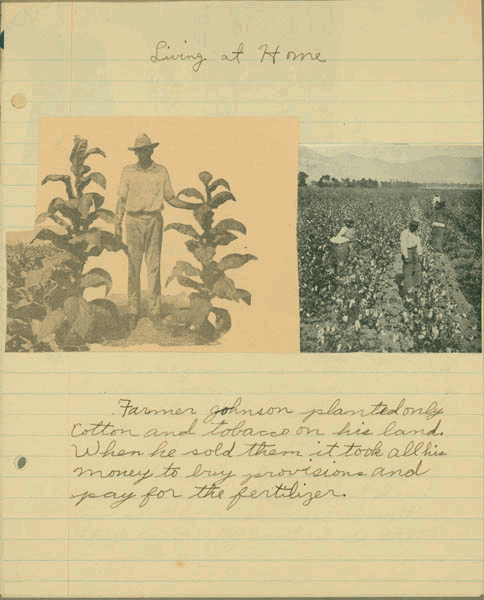

Following World War I, cotton and tobacco prices plummeted as demand decreased and overproduction glutted the market. Small farmers who relied solely on cash-crop cultivation suffered immeasurably while bills mounted and income declined. Tobacco prices, as high as eighty-six cents per pound in 1919, had fallen to nine cents per pound by the early 1930s (Daniel 1985; Abrams 1992). Cotton brought even less. Fertilizer bills alone often outweighed an entire year’s income, and farm families sank deep into debt. With all their acreage devoted to cotton and tobacco, more and more farmers resorted to purchasing their food on credit from merchants. As one of Gardner’s correspondents noted (Jones 1930), farmers had “neglected the raising of foodstuffs which ha[d] not only depleted their pocket books, but [was] the cause of so much ill health in families.” Diseases like pellagra—caused by a niacin deficiency—were on the rise, and thousands were hungry or malnourished.

Working with Gardner to analyze these problems, the State Board of Health reported that “a quarter of a billion dollars . . . goes out of North Carolina each year for foodstuffs . . . every single item of which could be raised in the state” (1929). Gardner and his supporters foresaw two interrelated solutions to the plight of farmers. By growing more of their own food, farm families would have sufficient sustenance without exhausting their meager cash supply. Devoting acreage to food crops would decrease the acreage going to cotton and tobacco, thereby reducing production and causing cash-crop prices to rise.

Early in his administration, Gardner set about defining and promoting this scheme, which he named the “Live-at-Home” program. He partnered with experts from the North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering (now North Carolina State University), the Department of Agriculture, and the Agricultural Extension Service to fine-tune the plan. On December 17, 1929, he held a luncheon at the Executive Mansion for more than two hundred newspaper reporters from around the state. At this first Live-at-Home Banquet, guests partook of a smorgasbord of food and drink produced in the Tar Heel State. (Greensboro News, December 17, 1929) These journalists became, in effect, partners with Gardner, promoting his program to hometown audiences.

Gardner believed that schoolchildren were crucial to the success of the program. As A. T. Allen, state superintendent of public instruction, wrote in a memo to the state’s educators (1930), “If the schools have a real place in the life of the State . . . they should be found in the forefront of this fight against ignorance and poverty.” All public schools—white and African American—implemented an obligatory Live-at-Home curriculum, where students learned the value of cultivating food, raising livestock, rotating crops, planting vegetable gardens, preserving food for winter, and selling excess. During Live-at-Home Week, February 10–14, 1930, children made scrapbooks, wrote letters to the governor, planted vegetable gardens, and encouraged their parents to participate in the program. Gardner publicly awarded grand-prize trophies in a statewide essay contest to high school students Leroy Sossamon and Ophelia Holley, despite warnings from his staff that being photographed with Holley, who was African American, might be politically imprudent (Morrison 1971).

Carrying on the governor’s initiative, local groups began hosting their own Live-at-Home events. Onslow County women planned an evening lecture and banquet complete with locally grown peaches, oysters, homemade pickles, baked ham, and yaupon tea. Johnston County businesses sponsored an elaborate homegrown feast accompanied by speakers from local and state extension agencies. In Cleveland County, the winner of an essay contest on “The Advantages of Diversified Farming” received a bull valued at five hundred dollars (Anon. n.d.-a; Anon. n.d.-b; Anon 1930).

Though a few critics chimed in, like a Charlotte wholesaler who complained that subsistence farming “isn’t the thing to do, we have got to have a market to sell and we have got to buy back from the market” (Williams 1930), public reaction to the program was overwhelmingly positive. Time magazine ran a story (July 7, 1930) on Live-at-Home, and even a South African newspaper reported on it, calling it “one of the best campaigns of which we have heard” (Umteteli wa Bantu, August 30, 1930). Local citizens also voiced their feelings about the program. James A. Starnes, of Harrisburg, wrote the governor that he was “living in a cotton growing section of N.C. where our fathers have been bred and born on such crop, [but] I am very much interested in hog and cattle raising” (1931). Jacob Sasser, of Goldsboro, suggested that farmers sign pledges not to plant “over 20 acres of land they cultivate in cotton” (1931).

For a short while, North Carolina’s Live-at-Home program captured widespread attention. Those farmers who increased their food-crop acreage surely felt the benefits of a varied diet and lower grocery bills, and citizens throughout the state learned about the advantages of diversified farming. However, the program fizzled out at the end of Gardner’s term in 1933, and since participation was voluntary, it ultimately did little to reduce cotton and tobacco acreage in the state. Many of the problems that Gardner attempted to tackle with the Live-at-Home strategy would again take center stage when President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs arrived in North Carolina.