See also: Disabled Veterans of the Civil War on ANCHOR

Listen to this entry

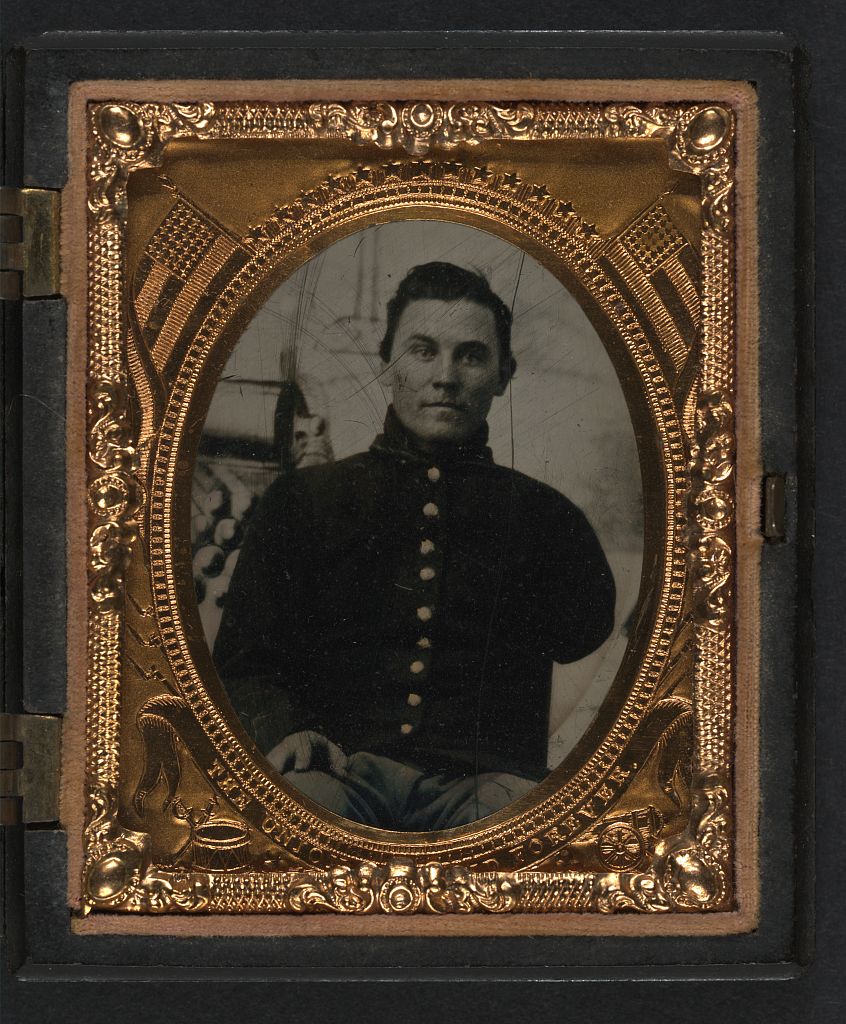

Many wounded soldiers during the Civil War (1861–1865), including those from North Carolina, had an operation called an amputation. In an amputation, a person has an arm or leg (or sometimes just a hand or foot) removed from their body because of a terrible injury or infection. Military advances before and during the Civil War meant more powerful, destructive weapons, and more devastating injuries, including shattered bones. Most American doctors, however, were unprepared to treat such terrible wounds. Their experience mostly included pulling teeth and lancing boils. They did not recognize the need for cleanliness and sanitation. Little was known about bacteria and germs. For example, bandages were used over and over, and on different people, without being cleaned.

With so many patients, doctors did not have time to do tedious surgical repairs, and many wounds that could be treated easily today became very infected. So the army medics amputated lots of arms and legs, or limbs. About three-fourths of the operations performed during the war were amputations.

These amputations were done by cutting off the limb quickly—in a circular-cut sawing motion—to keep the patient from dying of shock and pain. Remarkably, the resulting blood loss rarely caused death. Surgeons often left amputations to heal by granulation. This is a natural process by which new capillaries and thick tissue form—much like a scab—to protect the wound. When they had more time, surgeons might use the "fish-mouth" method. They would cut skin flaps (which looked like a fish’s mouth) and sew them to form a rounded stump.

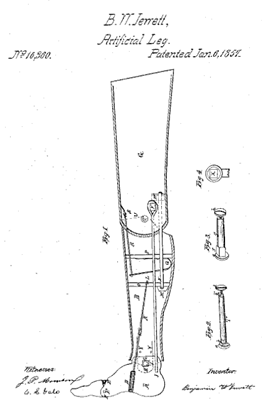

For soldiers who survived amputation and infection, it was natural to want an artificial, or fake, limb—both for looks and for function. An artificial arm will not provide a firm handshake, and an artificial leg will not get rid of a limp. But a prosthetic (another word used for an artificial limb) helps an amputee be less noticeable in public and offers the chance of a more regular daily life. Artificial limbs, especially legs, helped Civil War amputees get back to work to support themselves and their families. Agriculture had declined with so many soldiers away from home. After the war ended, it was important for men to return to their farms and increase production of food and money-making crops. Amputees were no different—they needed to be able to work on their farms, too.

North Carolina responded quickly to the needs of its citizens. It became the first of the former Confederate states to offer artificial limbs to amputees. The General Assembly passed a resolution in February 1866 to provide artificial legs, or an equivalent sum of money (seventy dollars) to amputees who could not use them. Because artificial arms were not considered very functional, the state did not offer them, or equivalent money (fifty dollars), until 1867. While North Carolina operated its artificial limbs program, 1,550 Confederate veterans contacted the government for help.

One Tar Heel veteran, Robert Alexander Hanna, had enlisted in the Confederate army on July 1, 1861. Two years later at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Hanna suffered wounds in the head and the left leg, just above the ankle joint. He suffered for about a month, with the wound oozing pus, before an amputation was done. After the war, Hanna received a wooden Jewett’s Patent Leg from the state in January 1867. According to family members, he saved that leg for special occasions, having made other artificial limbs to help him do his farmwork. (One homemade leg had a bull’s hoof for a foot!) The special care helped the Jewett’s Patent Leg last. When Hanna died in 1917 at about eighty-five years old, he had had the artificial leg for fifty years. It is a remarkable artifact—the only state-issued artificial leg on display today in North Carolina. Hanna’s wooden leg, as well as Civil War surgical equipment, may be seen at Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site in Four Oaks.