North Carolina's Role in Early National Government

During the Revolution, the states had approved the Articles of Confederation establishing a weak central government. Under the Articles, there was no chief executive and no national court system. What power the Confederation government had was consolidated in a one-house Congress, but Congress lacked the power to tax or to regulate commerce. Each state, regardless of population, had one vote in Congress. Important pieces of legislation required a supermajority, and amendments to the Articles required the unanimous consent of the states. By the mid 1780s, nationally minded politicians like James Madison of Virginia had concluded the Articles needed to be strengthened or replaced, but North Carolina’s Thomas Burke, who had argued as a member of Congress that the Confederation government wielded too much power, better reflected public opinion in the Tar Heel state.

Conservatives, however, supported constitutional reform and when Congress invited the states to send delegates to Philadelphia for a constitutional convention to meet in May 1787, the General Assembly complied. The North Carolina delegation played a relatively minor role in Philadelphia, although William Davie cast a crucial committee vote in favor the Great Compromise allocating seats in the House of Representatives based on population while giving each state an equal vote in the Senate. To North Carolina’s radicals, the new Constitution meant higher taxes and the collection of British debts, and when delegates were elected to a Hillsborough convention to consider ratification of the Constitution, Anti-Federalists, as opponents of the Constitution were known, won a lopsided victory over its conservative, Federalist supporters.

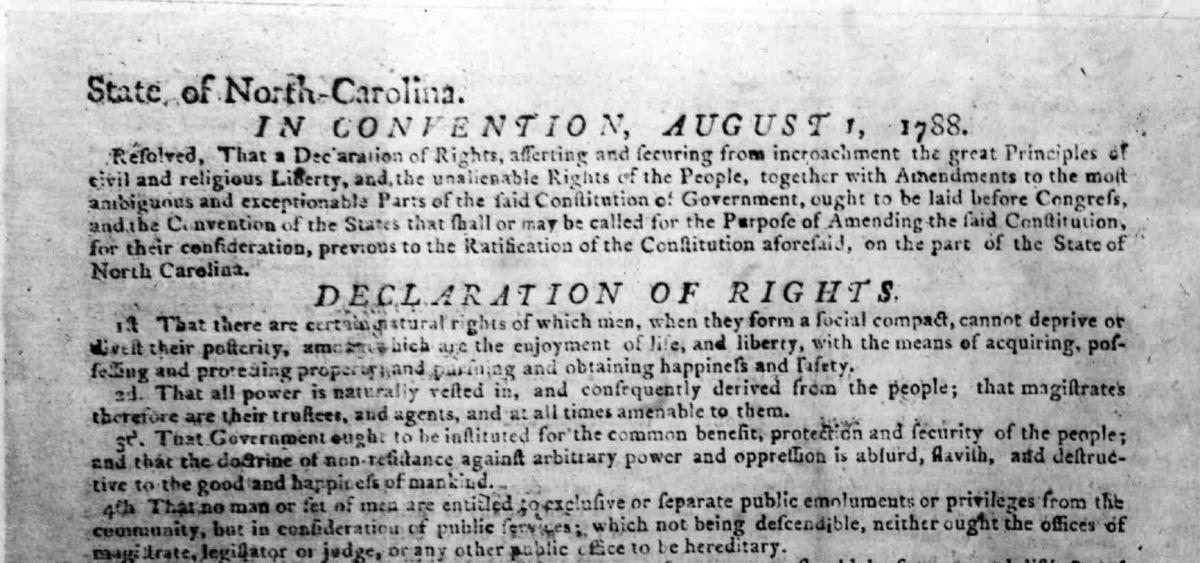

Anti-Federalists had also complained that the Constitution lacked a bill of rights to protect individual liberties. At the Hillsborough convention, Anti-Federalists led by Willie Jones of Halifax voted to take no action on the new Constitution, but recommended a series of amendments. By the time the Hillsborough convention met, ten states had already ratified the document, and New York approved it while the convention was setting. Knowing ratification was inevitable, Anti-Federalists hoped to win some desired amendments by withholding the state’s approval.

As the new government went into operation without North Carolina, Federalists like James Iredell continued to campaign for ratification. North Carolina attempted to maintain cordial relations with the federal government. The state, for example, collected customs duties on behalf of the new government and in exchange received an exemption for its own exports to the United States. The situation nevertheless could not be sustained; the exemption from custom duties was only temporary. After Congress approved a Bill of Rights--but before the amendments had received the approval of three-fourths of the states--a second convention met at Fayetteville and ratified the Constitution, without great enthusiasm.

With the approval of the Constitution, conservatives enjoyed a brief ascendancy in North Carolina politics, but many of the state’s Federalists were Federalists only in the sense that they had supported ratification. They could not embrace the more aggressive agenda of the New York Federalist Alexander Hamilton, who served as the first Secretary of the Treasury. Hamilton’s proposal to refinance the national debt at face value and to assume the states’ Revolutionary War debts provoked outrage in North Carolina, where people believed it would benefit Northern speculators and lead to higher taxes. Most Anti-Federalists and many Federalists began to drift into a new Democratic-Republican, or Republican, Party. In 1793, a prominent radical, Alexander Martin, replaced the veteran conservative Samuel Johnston in the United States Senate. There Martin joined the Federalist-turned Democratic-Republican Benjamin Hawkins, and in the House of Representatives, eight of the state’s ten members were leaning toward the Democratic-Republicans. The unpopular Jay Treaty with Great Britain only further undermined North Carolina’s Federalists, as did a claim by Congress that the state owed it money for costs incurred during the Revolution.

The threat of war with France briefly revived the Federalists as voters rallied around Washington’s Federalist successor, John Adams, in a moment of crisis. The Federalist William Davie won the governorship in 1798. But the Federalist revival proved short lived. North Carolinians could support Adams’s measured response, combining diplomacy and a limited naval war, to French attacks on American shipping; they could not support Federalist efforts to stifle dissent with the Alien and Sedition Acts. In the 1800 presidential race, North Carolina gave the Republican Thomas Jefferson eight electoral votes to four for Adams.

A common theme, the widespread fear of government, persisted through the period from 1776 to 1800. In part that fear flowed naturally from memories of British rule, but more fundamentally it reflected popular assumptions about the nature of government. To many, government activism meant policies designed to promote a nation’s commerce. Commercial development required sound money, and a limited money supply made it difficult for cash-strapped farmers to pay their bills. Worse yet, a robust judiciary meant the expeditious collection of debts. Government also meant standing armies, large navies, and sound public credit, all of which meant burdensome taxes. Small farmers, isolated by a poor transportation system from global markets, saw no benefit from the creation of a powerful nation-state linked to an international economy. Revolutionary-era conservatives and later Federalists could win occasional victories, but those who mistrusted centralized political power probably better represented the views of most white citizens, and their successes, for better or for worse, would be more enduring.