Quaker Abolitionists

by Mark Andrew Huddle

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 1996.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

The antebellum years were dangerous times for anyone with the temerity to preach an abolitionist gospel in the South. But in the last months of 1847, a young Wesleyan Methodist missionary, the Reverend Adam Crooks, came to North Carolina to minister to a small circuit of antislavery churches. Needless to say, Crooks felt anxious as he entered the Old North State to take up his mission assignment.

The antebellum years were dangerous times for anyone with the temerity to preach an abolitionist gospel in the South. But in the last months of 1847, a young Wesleyan Methodist missionary, the Reverend Adam Crooks, came to North Carolina to minister to a small circuit of antislavery churches. Needless to say, Crooks felt anxious as he entered the Old North State to take up his mission assignment.

After settling in Jamestown in Guilford County, Crooks was shocked to find a surprising number of people who held similar feelings about the "peculiar institution." In one of his first reports to the True Wesleyan, his denomination's newspaper, Crooks offered this interesting insight:

There is much more antislavery sentiment in this part of North Carolina than I had supposed. This is owing in great measure, to the Society of Friends [more commonly known as Quakers]. It is said the treatment of slaves is much modified by their presence; and as they are numerous in this community, slavery is seen in its modest form. It is some what amusing too, that I am taken for a Quaker, go wherever I will. I attended their meeting . . . and even the Friends themselves, thought I was one. . . . This I suppose is owing some to the doctrine I inculcate, and partly to my plain coat.

At the time of Crooks's mission, North Carolina Quakerism was in decline. Quakers, also called Friends since they were members of the Society of Friends, had spent decades leading an antislavery witness in North Carolina. By the late 1840s, this long struggle had taken a severe toll on the denomination. Many Quakers migrated from their North Carolina farms to free-soil territories in the far North and the new West. Others converted to other denominations. Still, the Friends of North Carolina had an important impact on the slavery debate during the antebellum period, and their exploits are an important chapter in the history of this period.

Quakers and the Issue of Slavery

Interestingly, in the early days, slavery was not an issue of conflict among North Carolina's Quakers. In fact, Quaker antislavery sentiment evolved slowly over many years. Although questions of conscience did occasionally arise, slaveholding was not prohibited in Quaker doctrine. In the 1750s, though, a New Jersey Quaker named John Woolman took up the antislavery cause and traveled widely to denounce the evils of slavery.

Woolman reached North Carolina in 1757 and addressed meetings in the Albemarle counties of Perquimans and Pasquotank. Woolman feared that slavery bred callousness toward humanity that was degrading to the slaveholder as well as the enslaved, and he counseled slaveholders to end their association with slavery immediately.

In the meantime, the center of Quakerism in North Carolina was shifting westward to the Piedmont, where Friends were traveling down the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road from northern colonies. Many of these Quakers brought with them a profound dislike of slavery. As a result, the Western Quarterly Meeting of the Society of Friends, the group that encompassed local meetings in the Piedmont, became a hotbed of abolitionist sentiment.

Conflict over the buying and selling of humans grew in local meetings. Again and again, throughout the 1760s and 1770s, the Western Quarterly Meeting questioned the North Carolina Yearly Meeting about how to deal with the slavery issue. Surprisingly, the most pressing problem facing North Carolina Friends concerned the manumission, or freeing, of their own slaves.

Quaker Dilemma: Manumission in North Carolina

In 1741 a colonial law [chapter XXIV, section LVI] had been enacted that forbade the manumission of slaves except as a reward for outstanding, or meritorious, service to the state. County courts had the authority to decide the merits of service for each individual case and then, if freedom was granted, gave freed slaves six months to leave the state. Many enslaved persons were freed for serving in the American Revolution.

As the slavery issue grew more troublesome, many Quaker slaveholders were caught in a dilemma. To continue owning slaves was becoming increasingly frowned upon in their society. However, to free their slaves just because they wanted to or because they felt they should was illegal. In April 1774 Thomas Newby of the Perquimans Monthly Meeting expressed his desire to free his slaves and requested guidance on the delicate question.

Newby's petition sparked a heated debate that resurfaced in meetings for nearly two years. Finally, in 1776, the Yearly Meeting created a committee for the express purpose of working with Friends who wished to free their slaves. Newby and ten other Quaker slaveholders then freed forty slaves—a direct violation of the 1741 law.

Even though North Carolina was helping its new nation fight the American Revolution in 1776, the legislature took notice of the Quaker action. Officials were enraged and accused the Quakers of attempting to start a slave rebellion. In response, the legislature moved to strengthen the 1741 law by empowering county courts to seize illegally freed slaves for immediate resale.

This step marked the beginning of a long series of legal battles between the state and North Carolina Quakers. These struggles continued well into the 1800s and caused great hardships among the Friends.

Quaker Efforts at Freeing Slaves

The North Carolina Yearly Meeting in 1808 acted to relieve the burdens of its slaveholding members. Taking advantage of a 1796 statute that allowed societies to buy and sell property, the Yearly Meeting authorized its members to transfer title of their slaves to the Yearly Meeting itself. By 1814, the group was the legal owner of nearly eight hundred slaves—the Society of Friends was one of the largest slaveholders in the state!

The North Carolina Yearly Meeting in 1808 acted to relieve the burdens of its slaveholding members. Taking advantage of a 1796 statute that allowed societies to buy and sell property, the Yearly Meeting authorized its members to transfer title of their slaves to the Yearly Meeting itself. By 1814, the group was the legal owner of nearly eight hundred slaves—the Society of Friends was one of the largest slaveholders in the state!

The Yearly Meeting created a special committee to oversee these slaves. For the most part, these slaves were allowed to have more freedom than they had experienced as plantation slaves. They usually worked with less direct supervision and were often "hired out" as individual laborers. The committee saw that proceeds from their labors went toward a fund for their care and eventual resettlement to free territories in the North and West. This short-term solution was accompanied by strenuous lobbying efforts to convince the state to reform its manumission laws.

One lobbying group was the North Carolina Manumission Society, which was formed in 1816. The Manumission Society was made up of Quakers and other antislavery supporters. Called Manumissionists, members advocated the gradual emancipation of slaves. They appealed to Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Moravian organizations for support in petitioning state and national governments for action, sent delegates to national antislavery conventions, and promoted black education. By 1824, many of the North Carolina Manumission Society's members were involved in a number of colonization schemes aimed at relocating former slaves to Africa.

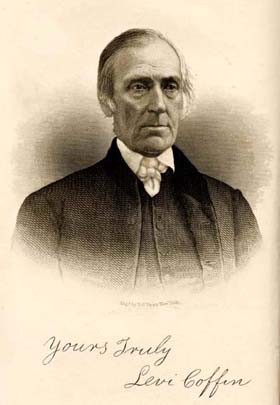

Probably the most legendary of the Quaker antislavery efforts was the Underground Railroad. The "conductor" of the so-called railroad was Greensboro's Levi Coffin. One "terminus," or end, of a route in North Carolina was rumored to be the New Garden Meetinghouse in Guilford County, where escaped slaves allegedly hid in the woods until they could resume travel at night to avoid detection.

Although its membership diminished during the antebellum years, the Society of Friends continued to exert a powerful influence in the state. No doubt because of that Quaker influence, other antislavery groups found the central Piedmont to be fertile ground for planting their beliefs.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: American Abolitionists. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/AmericanAbolitionists.pdf

References and Additional Resources:

Books by and about John Woolman, from the Internet Archive.

Coffin, Levi. 1880. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, the reputed president of the Underground Railroad... Cincinnati: Robert Clark & Co. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/coffin/menu.html

Crooks, E. W. 1875. Life of Rev. A. Crooks, A.M. Syracuse: D.S. Kinney. https://archive.org/details/lifeofreverendac00croouoft

Dannheisser, Ralph. 2008. "Quakers played major role in ending slavery in United States" U.S. Dept. of State

Resources on slavery and Quakers in libraries [via WorldCat]

Image credits:

Adam Crooks, from Crooks, E. W. 1875. Life of Rev. A. Crooks, A.M. Syracuse: D.S. Kinney. https://archive.org/details/lifeofreverendac00croouoft

Levi Coffin, from Coffin, Levi. 1880. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, the reputed president of the Underground Railroad... Cincinnati: Robert Clark & Co. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/coffin/frontis1.html

1 January 1996 | Huddle, Mark Andrew