Excerpted from More Than The ‘Physical Remains of Yesterday’s Industry:’ A Case Study of The Clayton Cotton Mill, by Abigail McCoy.

The state of North Carolina has a rich history of textile production dating back to colonial times. Cotton was abundant throughout North Carolina and the cost of establishing textile mills was relatively low, encouraging the establishment of the textile industry in the state. During the late nineteenth century, individual men began to gain more economically from the textile industry but remained diversified in their interests. Ashley Horne was one such individual, and in 1900, he established the Clayton Cotton Mill in the town of Clayton, North Carolina. Agriculture had always been important to the area, but with the establishment of textile mills, Clayton’s economy grew drastically and so did its population. The history of the Clayton Cotton Mill closely mirrors the patterns of North Carolina’s textile industry, especially in relation to paternalism, child labor, and race relations.

The Clayton Cotton Mill was the first of three cotton mills established in the town. The initial funding for this venture came from the Bank of Clayton where Horne was president, and the mill was established near the rail line which ran through Clayton. Its location next to the rail track made for easy movement of the almost 500-pound bales of cotton.

Excitement ran high at the introduction of this new industry in Clayton. The opening of the mill is described in a local newspaper from 1901:

The machinery of the new Clayton Cotton Mill began whirring. It was started when Little Ms. Swannanoa Horne, the daughter of President Ashley Horne, of the mill, pressed the electric button which set the machinery throbbing through the building…the mill has 5,000 spindles and the machinery is of the best and latest manufacture, the structure being handsomely and perfectly made.

A mill village was constructed for the laborers who worked at the cotton mill. The layout of the mill, including its associated village, was based off Daniel Tompkins’s 1899 textbook Cotton Mill, Commercial Features: A Text-book for the Use of Textile Schools and Investors. Tompkins’s influence can be seen not only in the physical layout of the complex, but also in the attitudes, standards, and norms adopted by those who owned the mill and those who worked there.

Daniel Tompkins’s Cotton Mill, Commercial Features was the handbook for paternalism at that time. It detailed many ways mill owners could exercise control over mill laborers to create an “ideal” workforce. Some of Tompkins’s suggestions included keeping the mill just outside of city limits to avoid its jurisdiction, having a company store to control what laborers were purchasing, providing just enough land with each house for a garden, and providing amenities to keep the laborers happy.

Tompkins stated in his work that although so many family members would be employed at the mill that they wouldn’t have much time for gardening, “it is well to encourage the planting of vegetables and flower gardens, as being conducive to general contentment among the operatives themselves, and as being an advantage to the mill company in making a cleanly and attractive property.” His belief that textile laborers could be exploited through long hours and low wages as long as they were balanced with space for gardening and flowers reflected the general approaches to laborers at the time. Ashley Horne followed many pieces of Tompkins’s advice at the Clayton Cotton Mill, such as including a garden plot at every mill house. There was also a designated area away from the houses for raising and slaughtering pigs.

Horne also followed Tompkins’s advice by allowing a store to be placed adjacent to the housing in the mill village. Most laborers flocked to the store after the bell rang releasing them from work, purchasing Capudine, soda, and other necessities. The company store was also a gathering place for men and young boys to play marbles or to throw coins, as well as to plan out the schedule for butchering their pigs. A baseball field and sponsored team, a playground, and a boxing ring were all provided by the mill as part of the paternalistic effort to maintain control of the workforce.

Tompkins’s Cotton Mill, Commercial Features also discussed labor and race, providing insight into widespread views of those in the North Carolina textile industry at the turn of the century. On the topic of the South’s ability to be competitive in manufacturing, he discussed the “chaotic disorder” instigated by the abolition of slavery and the struggles it brought regarding the balancing of social status for White people and Black people.

Tompkins reported that Black laborers were “sometimes used for draymen, firemen and other such purposes where there is little or no contact with the white organization” and that Black women “work[ed] very well” in laundries. After a discussion of attempted and failed efforts to employ Black laborers in mills, he reported “the best judgement would seem to be that they will never be available as cotton mill operatives except in more menial occupations.”

Ashley Horne also heeded Tompkins’s advice regarding race at the Clayton Cotton Mill by not employing any Black laborers. Federal Census data from 1910 through 1940 and informant data corroborate this, indicating that all people who lived in the mill village were White. The J.A. Vinson Planing Mill, which was directly adjacent to the cotton mill, only employed Black laborers for working with draft horses or in other positions that required heavy manual labor. These laborers were transient workers and lived in shanties away from the mill village. While these Black laborers weren’t employed by the cotton mill, the proximity of the two mills meant that the textile mill laborers would have seen and probably interacted with these workers.

The only other Black individuals who entered the mill village were those who were hired by mill hands to help with washing or other domestic chores. One man who grew up at the Clayton Mill from the early 1930s until 1951 remembered that his mother hired a Black woman to help with the washing. She had to walk in the middle of the street, carrying a stick to keep the dogs away from her. It is interesting to note that these mill laborers, who were often looked down upon by the rest of the town for their economic status, were still able to hire and have authority over their Black neighbors in a way that reinforced racial inequity.

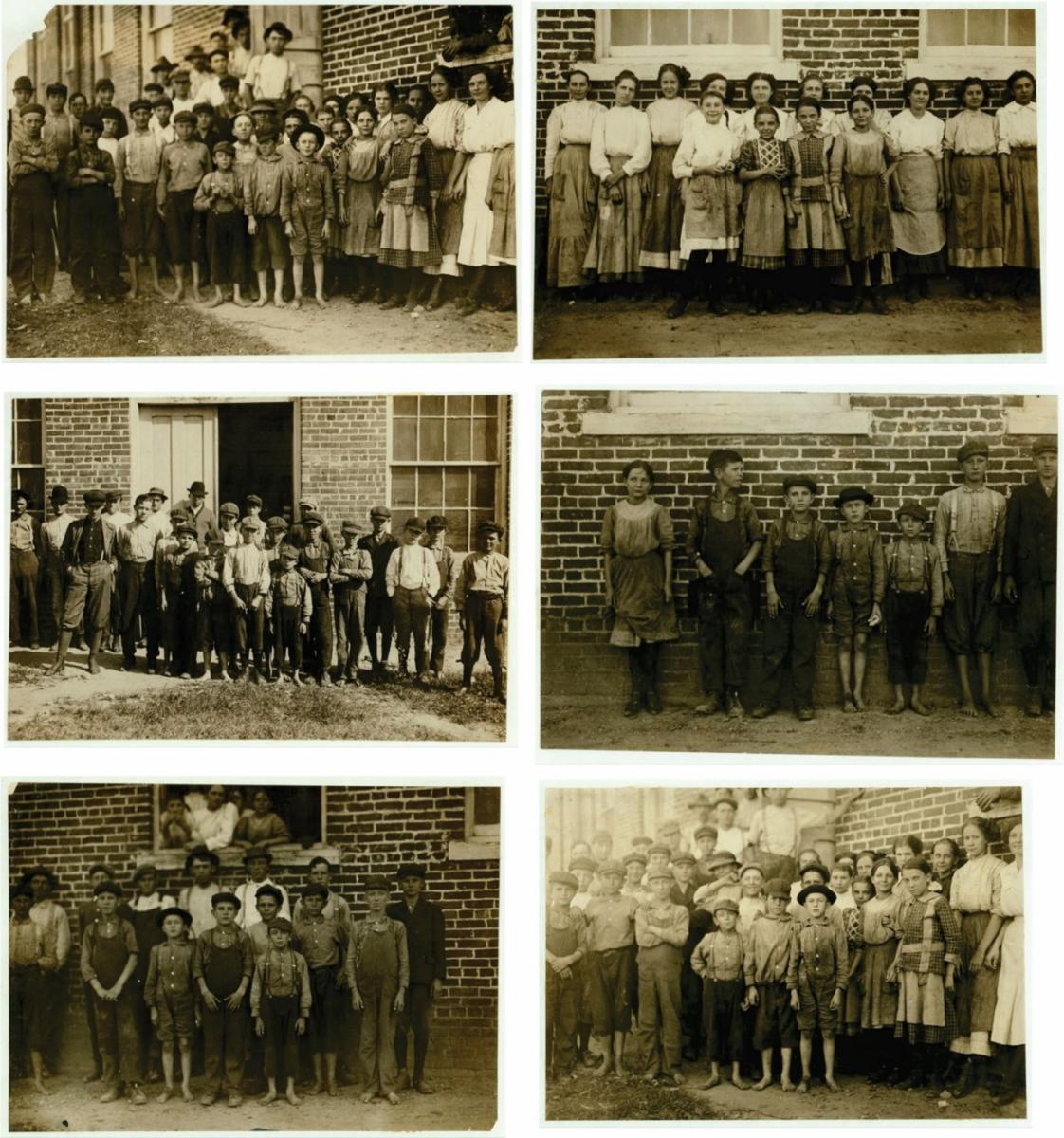

In 1912, Lewis Hine, an investigative photographer, documented child labor within the textile industry for the National Child Labor Committee. He arrived in Clayton in October of 1912 and took photographs of child laborers at the Clayton Cotton Mill.5 These photographs were all taken outside of the mill, as managers did not allow Hine to document the working conditions inside. Since he was often denied access to industrial buildings he primarily only “photographed children as they entered and exited the workplace.” Hine witnessed children exiting locations that housed warping machines and looms, two areas children were generally not thought to work. He stated that he “talked with a boy recently who said he was ten years old and works in the Clayton Cotton Mill [and] also that others the same age worked. (The Superintendent watched the photographing without comment.).” He also notes that he was unable to document any of the youngest girls in the photographs.

Census data provides numbers concerning child labor and the trends from 1910 to 1940, though it is possible that these numbers are not necessarily accurate. At the Clayton Cotton Mill, children younger than 14 were no longer listed as employed by the mill beginning with the 1920 census. This was likely to avoid an official record of illegal labor practices, although most textile mills ignored labor laws as there was little enforcement and even fewer inspections. It is likely that young children continued working at the Clayton Cotton Mill until 1938, when a federal law regulating child labor was implemented.

While the official records of the Clayton Cotton Mill list no children younger than 14 employed at the mill after 1920, people were drawn to the mill at this time largely due to the promise of employment for their children. One man remembers that when his grandfather first arrived at the mill in the 1920s, there were children around the ages of twelve to fourteen being paid to work at the cotton mill.

The Clayton Cotton Mill underwent several ownership transitions during its operation. After 1927 it was leased to Rockfish Mills and renamed the Claytex Mill but was soon closed in 1930 due to the Great Depression. The Clayton Cotton Mill was purchased in 1935 at auction by R.B. Whitley, a business associate of Ashley Horne, and renamed The Whitely Cotton Mills. Whitley sold the mill in 1946 to LaFar Industries Group of Gastonia, who renamed the mill to the Clayton Spinning Company.

A study conducted in 1965 noted that the town of Clayton was home to six industrial factories, creating an annual payroll of $2 million. The Clayton Spinning Company (previously the Clayton Cotton Mill) and the Bartex Spinning Company were recorded as employing around 700 skilled and semi-skilled workers. The wages of textile mill workers were noted as between $1.25 and $2.25 per hour, and the report claimed that there were no labor unions present in any of Clayton’s industries, noting “an outstanding spirit of cooperation” between the industries and the town.

The Clayton Spinning Company ceased operation in 1976, 76 years after the mill first opened. The rising price of cotton was cited as the reason for the closure, which left 100 laborers unemployed, including among them some who had worked at the mill for 45 years. Cotton prices and the increasing relocation of the textile industry to other developing countries led to many operations closing in the United States at this time and thereafter. Derelict industrial buildings soon became a common sight throughout North Carolina, testaments to the state’s once thriving textile industry.