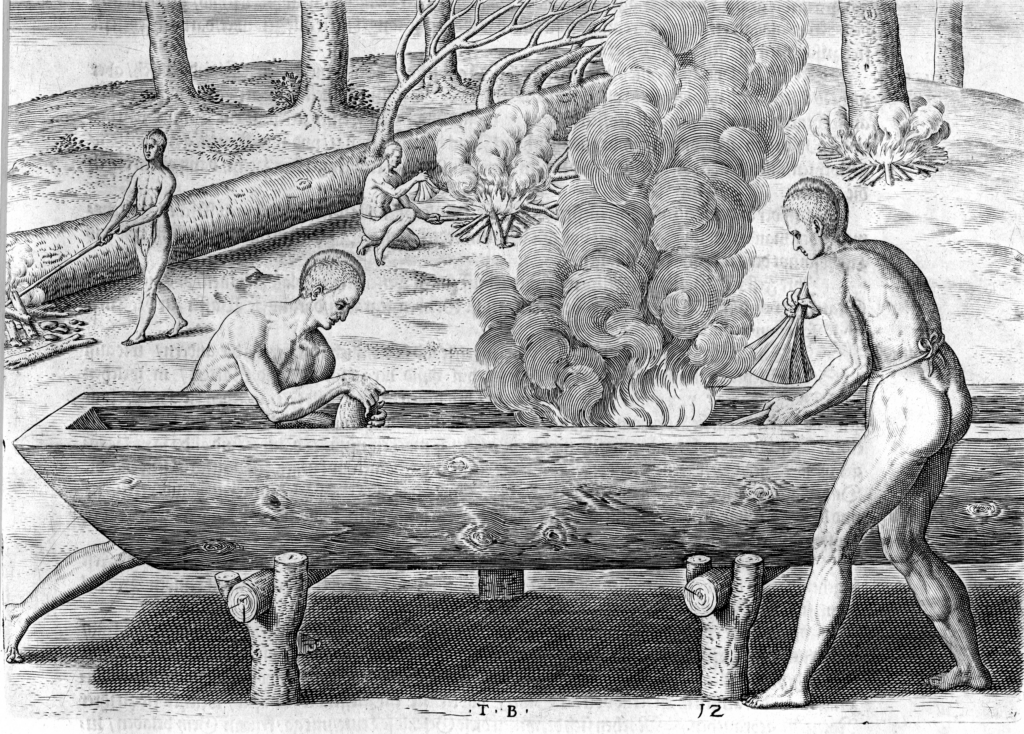

Canoes have provided a primary form of transportation on the sounds, rivers, and bays of coastal North Carolina for centuries. In the 1580s the explorers and colonists sent to Roanoke Island by Sir Walter Raleigh found Indians traveling throughout the labyrinth of estuarine waters in long, narrow log canoes, some large enough to carry 20 men and their gear. Lacking iron tools, the Native Americans used fire and sharp shells to build their canoes in a time-consuming process that began by maintaining a small, controlled fire near the base of a selected tree until the tree fell down. They repeated the process, burning through the fallen trunk at the chosen spot. They elevated the log on a frame and, using gum and rosin to stoke the fire, burned deep enough to form coals that were scraped away with the shells. This process was repeated until the desired depth was reached.

One of the preferred woods used for canoes appears to have been juniper (white cedar), which grew in great profusion throughout swampy areas of coastal North Carolina. Juniper is still valued by local boatbuilders because it is soft, lightweight, and extremely resistant to rot. So impressed were the Europeans with the finished products that one of Raleigh's men said the natives "knowe how to make them as handsomelye . . . as ours."

When permanent settlers arrived, it was logical for them to use locally available juniper wood for their own small craft. With sharp axes and other tools, it was no doubt easier to make a canoe out of a single log than to have the log cut into boards in order to construct a more traditional small boat from scratch. Following the lead of earlier settlers in the Chesapeake Bay area, North Carolina settlers began to adapt the dugout canoe technique used for small boats to larger ones that could carry more cargo. Early efforts resulted in a process in which a log was split down the middle and another piece was added between the two original canoe halves, more than doubling the capacity of the little craft. Concurrent with this innovation was the development and use of what was called a "tobacco canoe." This simple form of catamaran consisted of two log canoes lashed together side by side, across which as many as eight or nine hogsheads of tobacco could be placed. A more sophisticated form of the two-log dugout canoe evolved with the selection of matching logs (often cypress as juniper became more difficult to find) and the fitting of the two together in the construction process. The smaller of these were called kunners; the larger ones became known as periaugers.

In time, canoe builders began producing three-log canoes, not just because they were larger than the earlier dugouts but also because it was sometimes considered easier to work with several small logs than with a single large one. In time, even more logs-as many as five and possibly more-were utilized, until dugouts were being used in the North Carolina sounds and rivers and, in some cases, in trade with other East Coast ports and even with the Caribbean. The widespread use of dugout canoes continued through the nineteenth century, and dugouts used as workboats, as well as more sleek models designed for canoe racing, remained popular well into the twentieth century.

Flat-bottomed skiffs and stick-built canoes gradually replaced smaller dugout canoes, including those known as punts. In recent years, the popularity of one-man canoes has faded. The craft has been replaced on the sounds and rivers by a first cousin, the one-man kayak. In the modern era, there are probably more kayaks on North Carolina's coastal waters than there were Indian dugout canoes when the Europeans first discovered the area.