Caledonia, located just south of the Roanoke River in Halifax County, North Carolina, has undergone many changes in its 300 year history. Starting in the early 18th century, Caledonia was settled by early immigrants to North Carolina. It later became part of the large system of plantations owned by the Johnston family, where various crops were grown through the efforts of hundreds of enslaved people. That tradition of agricultural cultivation continued into the 20th century when Caledonia became North Carolina's largest prison farm, a title that it still holds today.

The name Caledonia predated the plantation itself. Starting in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, a small stream of settlers began acquiring plots of land south of the Roanoke River in what later became Halifax County. Many of these settlers were Scottish, arriving either directly from their home country or, more commonly, from Virginia. One of those early settlers named the area Caledonia after the Latin word for Scotland. The first recorded mention of Caledonia came in 1712 when William Maule was granted "six hundred and forty acres on the South side of Moratock (now Roanoke) River" at a place called "Calladonia [sic]."Over the next few years William Maule, William Cathcart, and others acquired thousands of acres in a small region on the southern banks of the Roanoke River they continued to call Caledonia. The first step in turning this loose assortment of lands into a plantation came when William Cathcart married his neighbor Penelope, the daughter of William Maule. He thus acquired much of the land belonging to his new father-in-law. This sort of advantageous marriage was repeated a generation later when William and Penelope's daughter, Frances Cathcart, married Samuel Johnston, a politician and lawyer from one of North Carolina's most prominent families. Upon their marriage in 1770, Samuel and Frances Johnston were given "one half or moiety of all that tract or parcel of land known and distinguished by the name of Caladonia [sic] lying on the South side of Roanoke river in Halifax County containing by estimation three thousand acres." This formed the nucleus of Caledonia Plantation which the Johnston family would own and expand for almost a century afterward.

An immensely wealthy and successful planter, Samuel Johnston successfully managed Caledonia and his other plantations, but they were always secondary to his prominent political career. Still, when Samuel Johnston died in 1816, he had increased the size of Caledonia significantly. His son, James Cathcart Johnston, inherited thousands of acres and hundreds of slaves when his father died. James Cathcart Johnston dedicated himself to managing the plantations he inherited, and by 1860 had increased the size of Caledonia to 7834 acres of land, worked by 271 slaves. A life-long bachelor, J.C. Johnston had no children and often disagreed significantly with members of his extended family. Yet upon his death in 1865, it came as a surprise when he left all of his holdings not to family, but to friends and employees. Caledonia, the largest of his plantations, was willed to its overseer, Henry Futrell. But more momentous were the massive changes brought by the Civil War. Slavery was ended, leaving to Henry Futrell a plantation changed entirely. The former slaves of the plantation now held the fate of the land squarely in their hands.

In the year of combined ownership and management before his death late in 1866, Futrell and the newly freed slaves struggled to work out a compromise to keep the productive fields from lying fallow, balancing their desires for freedom with economic and political reality. The two sides eventually came together in an agreement brokered by the newly-established Freedmen's Bureau. The former slaves of Caledonia agreed "to do and perform all sorts of labor, such as is usual and necessary to be performed" in exchange for rudimentary shelter, rations, and nominal pay. This document was meant to serve as a contract for the year 1866. The eighty four men who signed this document, along with their families, worked the land for at least that year and probably for many more afterward. After Henry Futrell's death his family continued to own the land and cultivated part of it with the aid of sharecroppers who had previously worked the land in bondage. By the late nineteenth century, the four surviving children of Henry Futrell were frustrated with the high price of producing a crop in a South without enslaved labor. But, even without the labor that had made the plantation such a profitable venture, the land still held the potential for profit. By 1891, 7290 acres of the almost 8,000 amassed at Caledonia remained. The next phase in Caledonia's existence marked a transformation profound as that from slavery to sharecropping and proved its continued agricultural viability.

During the waning months of 1891, North Carolina authorized the signing of four separate leases that represented the entirety of Caledonia. The original lease was to run for ten years with the option to purchase the land at any point. Caledonia thus became immediately the largest prison, by area, in North Carolina. The leasing and later purchase of Caledonia was part of a national trend; within the last ten years of the nineteenth century, many former plantations, including Parchman in Mississippi and Angola in Louisiana, were turned into prisons. In 1894, 8,600 acres were planted between four prison farms in North Carolina, 4,500 of those acres being at Caledonia. The prisoners were also steadily clearing more land to be planted, even as they dramatically increased the quantity of crops being produced. By 1900, the state recognized the increase in production and the value of Caledonia and purchased it outright for just over $60,000.

The next few years were successful ones at Caledonia, measured in agricultural productivity. The inmates of the prison continued to plant and harvest huge amounts of grains, vegetables, and cotton and to continually clear more land during each offseason. Caledonia was so successful that the North Carolina legislature introduced a bill in 1919 that proposed moving the entirety of the state's prison operations to Caledonia. After a delegation of politicians visited Caledonia, they realized its value and instead proposed to sell the land. After dividing Caledonia's almost 7,000 acres into 53 individual plots, the state auctioned off all but 1,200 acres to private individuals. This sale yielded just under $500,000, a remarkable return on the state's investment. It looked as if Caledonia was destined to be broken up into multiple plots with multiple owners, the way it had been two hundred years before when it was first settled.

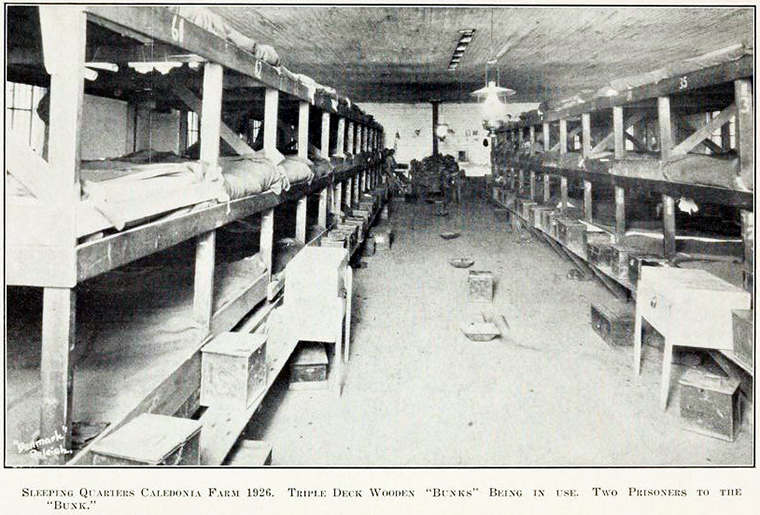

However, by 1921, a large part of the acreage sold by the state was in foreclosure. Whether these foreclosures were due to the flooding that had plagued the land for years, or the high prices that the State had demanded for its valuable land, they resulted in ownership of Caledonia reverting back to the state. By 1923, North Carolina had repossessed around 5,000 acres and was again farming it, as well as the 1,200 acres never sold. This renewed ownership was not without some changes. For the first time, the prison that year was referred to specifically as "Caledonia Farm in Halifax County for white prisoners," and was segregated by race. The land was divided into three camps, with the third being designated for African American inmates. The racism inherent in the system is further evidenced when a report from the 1927 refers to Caledonia as a place "manned by white prisoners… [that] requires more men to man the farm than if it were manned by actual farmers or Negroes."

In the 1920's, the prisons of North Carolina were increasingly and "extensively engaged in farming." Caledonia took an increasingly prominent role in the system as the largest prison farm in the state. At one point, the 6,500 acres of Caledonia were home to a third of North Carolina's prisoners. But as wages for prisoners increased and agriculture became less profitable, Caledonia quickly lost its place as the most valuable institution in the prison system. Starting in the early 1930's, Caledonia shifted its agricultural output "from cotton and other crop production, to food and feed, grain and livestock farming." Many buildings were turned over to other purposes;, the former prisoners' barracks became home to some of the 10,000 hens that provided eggs for much of the North Carolina prison system. By the mid-1950's, Caledonia was simply one of many prison farms in the state, all tasked with "produc[ing] the major portion of the food requirements" for North Carolina's prisoners. It was this model of reduced size and increased food production that Caledonia followed in the ensuing decades. Caledonia still operates as a prison farm today, though it holds only around 300 prisoners, a huge reduction from the multitudes that once lived and worked here.