13 Nov. 1900–8 Jan. 1975

David Marshall (Carbine) Williams, firearms inventor, was born in Cumberland County, the first of seven children of James Claud and Laura Kornegay Williams (his father had four other children by a previous marriage). The youngster worked on the extensive family farm, dropped out of school after eight grades, worked in a blacksmith shop, served a short time in the navy (he was discharged for being underage), and then spent one semester at Blackstone Military Academy before being expelled. In 1918 he married Margaret Isobel Cook, who bore him one child, David Marshall, Jr.

Following his marriage, Williams worked for a short time for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, but, unbeknownst to his wife, he built and operated several illicit distilleries near Godwin. During a raid on one of the stills in 1921, Deputy Sheriff Al Pate was shot to death and Williams was charged with first-degree murder. The trial ended in a hung jury, but, rather than face a second trial and a possible death sentence, Williams pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of second-degree murder and was given a twenty- to thirty-year sentence. At Central Prison in Raleigh and at a camp near Robbinsville, he proved to be something less than a compliant prisoner, but when the chained man was transferred to Caledonia State Prison in Halifax County, the superintendent, H. T. Peoples, began to observe in him a certain genius.

Even as a child "Marsh" Williams had shown a talent for fashioning objects with his hands, and as an adolescent he took a special interest in guns. When he was only ten he had made a workable pistol from a hollow reed and pieces of juniper wood, and in prison—for self-defense—he shaped daggers from scrap iron. He also squirreled away paper and pencils and stayed up late at night drawing designs for firearms. Increasingly impressed by the talents of his ward, Peoples assigned Williams to the prison machine shop, where the prisoner repaired the weapons carried by the guards. His remarkable skill permitted him to keep ahead of his work, leaving a great deal of spare time to apply to his own hobby. With scrap metal, hand files, and hacksaws, he began building lathes and other tools, then parts for guns. Tractor and automobile axles became receivers, bolts, and movable chambers; drive shafts became gun barrels and operating handles; magnets became cocking cams and extractors; walnut fence posts became stocks. Peoples, marveling over Williams's ingenuity and precision, risked his own safety and job security by allowing the convict to build complete weapons, some of which were hidden in the walls of the shop. The prisoner was aided by his mother who, in response to his letters, obtained technical data on various models of guns for him and provided his contacts with patent attorneys.

While in prison Williams invented the short-stroke piston and the floating chamber principles that eventually revolutionized small arms manufacture. Inevitably news of these experiments reached the outside, and on 28 Apr. 1928 the Charlotte News reported: "An invention that may revolutionize the firearms world, involving radical departures in rapid fire mechanisms as applied to the automatic rifle, has apparently been perfected by Marshall Williams." Within a few days the Colt Patent Firearms Company wrote to George Ross Pou, superintendent of prisons, who forwarded the letter directly to Williams. Later the company sent representatives to interview the prisoner.

Meanwhile, the respected Williams family and their friends in Cumberland County started a campaign to obtain a commutation of Marsh Williams's sentence. They were joined by the sheriff to whom Williams had surrendered and the widow of the man he was accused of killing. Governor Angus W. McLean reduced the sentence, and in September 1929 David Marshall Williams left prison.

Back on the farm in Cumberland County, Williams concentrated on perfecting his inventions; after two years he went to Washington and showed them to the War Department. His first contract was to modify .30 caliber Browning watercooled machine guns to fire .22 caliber long rifle smokeless ammunition. He accomplished the task with his floating chamber principle, the only known way of obtaining great operating energy from small cartridges. Patenting firearms improvements by the dozens, Williams launched a career that was to bring him fame and fortune. For instance, his floating chamber was used in a semiautomatic pistol by Colt, in a rifle by Remington, and in a machine gun by the U.S. Army. But it was the use of his short-stroke piston in the M1 carbine, manufactured by Winchester and other companies, that brought him his greatest fame and his nickname, Carbine (which, he insisted, was pronounced to rhyme with "grapevine"). More than eight million of these guns were made, and General Douglas MacArthur called the light, rapid-fire carbine "one of the strongest contributing factors in our victory in the Pacific."

Williams worked at various times as a consultant for the army and for firearms manufacturers, particularly Winchester. He bought a large house in New Haven, Conn., and spent liberally on classical music, diamonds, and whatever captured his fancy. But his wealth lasted only a short time.

Marsh Williams became a legend when in 1952 James Stewart portrayed him in the MGM motion picture Carbine Williams. As technical director of the movie, Williams spent time in Hollywood, then returned to Fayetteville to be honored on "David Marshall Williams Day," 24 Apr. 1952. In the Reader's Digest he was hailed by his former prison superintendent, H. T. Peoples, as "The Most Unforgettable Character I Ever Met." Other favorable magazine articles facilitated his return to Godwin, where in his machine shop he continued to perfect other improvements on firearms. In all, he eventually held more than five dozen patents. His reputation was largely rehabilitated (he always denied having fired the shot that killed the deputy sheriff, though he had taken the blame because he was the head of the crew), and he became something of an idol of law enforcement officials: he held honorary membership in the National Sheriffs Association and was appointed honorary deputy U.S. marshal and a second deputy sheriff of Cumberland County.

The General Assembly of 1971 adopted a joint resolution paying tribute to Williams for the "exemplary citizenship" that he had practiced since his release from prison. At the urging of Governor Robert W. Scott, Williams gave his machine shop—building, tools, models, and all—to the State Department of Archives and History. The structure and its contents were moved to Raleigh and reinstalled in the department's Museum of History.

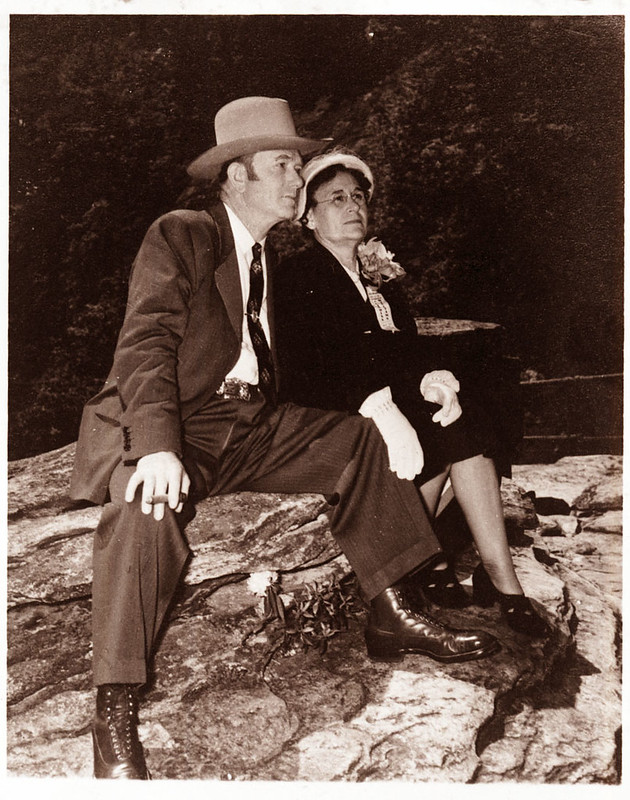

In his prime, Williams was 5 feet 9 inches tall, 180 pounds, with a ruddy complexion, reddish-brown hair, piercing blue eyes, and incredibly strong hands. He wore flaring sideburns down to the level of his mouth, and his dress was characterized by a wide-brimmed hat, a tooled leather belt with ornate buckle, and a revolver in a fancy holster. He was a man of unpredictable moods whose deep wounds of the past exhibited themselves in his suspicion of strangers. Yet, once his confidence was won, he could be a warm and generous being. Following his return to Godwin after the war, he and "Miss Maggie," who earned a teacher's certificate and taught school while he was away, lived quietly in a small, exceedingly modest country cottage without television or telephone. His name did not even appear on the mailbox beside the road. He continued to work regularly in his marvelously equipped machine shop until his health began to fail. Then, almost immediately following the ceremony opening the relocated shop in the Museum of History, he was hospitalized. He died at Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh and was buried in the cemetery of the Old Bluff Presbyterian Church near Wade.

A portrait of Williams by Walter Keul is owned by the family.