14 Nov. 1862–6 Mar. 1914

See also: Biltmore House; Biltmore Forest School; Biltmore Industries

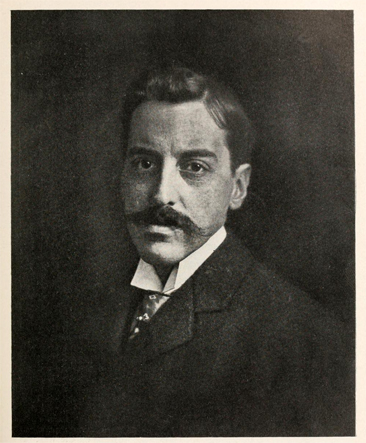

George Washington Vanderbilt, heir of a portion of the family fortune acquired in railroad development, turned his interests to agriculture and forestry and became outstanding in both. Born in New Dorp (now Richmond Borough), Staten Island, N.Y., the youngest son of William Henry and Maria Louisa Kissam Vanderbilt, he was educated by tutors and through world travel. Shy and serious, he cared little for finance but nevertheless increased his inherited fortune during his lifetime.

Fascinated by the mountains of western North Carolina, Vanderbilt began buying land south and southeast of Asheville in 1889. Eventually his holdings amounted to 130,000 acres, including Mount Pisgah (5,721 ft.), from the top of which may be seen points in South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Virginia, as well as in North Carolina. Within this area he sought the ideal spot for what he anticipated would be the most beautiful country home in the nation. Having studied architecture, forestry, and landscape gardening, he devoted himself wholeheartedly to the exciting task ahead. Working closely with architect Richard Morris Hunt, he developed plans that anticipated expansive views from every possible window. Temporary structures were raised to examine the view where windows would be, and in other ways as well Vanderbilt superintended the construction, the final cost of which was reported to have been $3 million. He invested millions more in improving the estate, which he named "Biltmore." Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park in New York City and of the capitol grounds in Washington, D.C., was engaged to develop plans for the estate grounds. Until the death of his widowed mother in 1896, Vanderbilt lived with her in New York. Although he inherited her Fifth Avenue mansion, the thirty-four-year-old Vanderbilt then went to live in his North Carolina château. On 2 June 1898 he married Edith Stuyvesant Dresser, of Newport, R.I., who proved to be a valued aide in the unique work he anticipated.

Vanderbilt became a scientific farmer and stockbreeder, as well as one of the pioneers in scientific forestry in America. His pedigreed hogs, raised for sale in local markets, were a significant improvement over the unimproved stock found in most of the mountain region. The milk production of one of his Jersey cows broke all records, and the milk and ice cream from his dairies were sold across a wide area. The significance of the example he set for improving livestock would be difficult to overestimate.

The Biltmore Nursery, featuring trees and plants of the Appalachian region, became an important part of the output of the Vanderbilt estate. A portion of his woodland was developed for pleasure—with bridle paths following the interesting terrain and picnic shelters conveniently located. Roads were also built to ensure the movement of fire-fighting equipment in case of forest fires.

Gifford Pinchot was the first superintendent of the wooded estate, and in 1898 he went on to become head of the U.S. Division of Forestry. Vanderbilt founded the Biltmore School of Forestry on his estate, where large numbers of young men received training. He planned and built the model village of Biltmore as a center for the employees on his property, as well as All Souls Church. He bought another home in Washington, D.C. but spent most of his time in the North Carolina mountains, overseeing the work of the estate, studying trees, bird, and animals, or doing research in his large library, which held many books on nature. He spoke eight languages and had a reading acquaintance with Hebrew and Sanscrit.

In the early 1900s Vanderbilt sold the timber rights in Pisgah Forest to the Carr Lumber Company for $12 an acre, the contract extending over a twenty-year period. During those years the estate netted about $870,000. Vanderbilt directed that weak and undesirable trees be removed first and that after an area had been selectively cut over, new trees be planted. Forests were to be "managed" and kept in constant production. He maintained that "private ownership of any resource necessary to the general welfare carries with it the moral obligation of faithful stewardship to the public." He stressed that he had "stuck to forestry from the beginning and I shall not forsake it now. For me to impair the future usefulness of Pisgah Forest in order to somewhat increase present revenues, would be bad business policy. But apart from that, it would be bad citizenship, as I see it, no man is a good citizen who destroys for selfish ends a good forest."

Vanderbilt might have received a much higher price for the timber if he had waived restrictions under this sale as to methods of cutting, but he required that the techniques of practical forestry be followed. An observer commented: "Pisgah Forest, its mountainous slopes clothed in an unbroken mantle of protective tree growth is his monument. He transformed it by nearly a quarter of a century's efficient fire protection from a forest characterized by scanty young growth, thin humus covering, and impoverished soil, as the result of injury it had received in former years from excessive grazing and recurrent fires, to one whose silvicultural condition is probably unequaled in the Southern Appalachians."

Among his benefactions, Vanderbilt in 1888 erected and presented to the New York Free Circulating Library (later New York Public Library) its Jackson Square Branch and gave to Columbia University the site on which the Teachers College was built. He also built a private museum in New York City, gave it art objects that he had collected all over the world, and presented it to the American Fine Arts Society. He offered to sell the major portion of his forest land to the United States for a forest preserve, but the offer was not accepted until 1916, after his death, when the government bought an 80,600-tract from Mrs. Vanderbilt to form the nucleus of Pisgah National Forest.

Following an operation for appendicitis about a week previously, Vanderbilt died at his Washington home of "a weak heart." In addition to his wife, he was survived by a daughter, Cornelia Stuyvesant. His body was placed in the family vault at New Dorp, Staten Island.