See also: Historically Black Colleges; North Carolina Central University

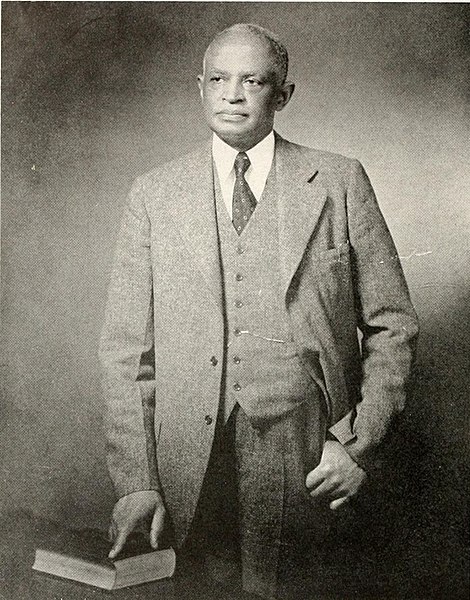

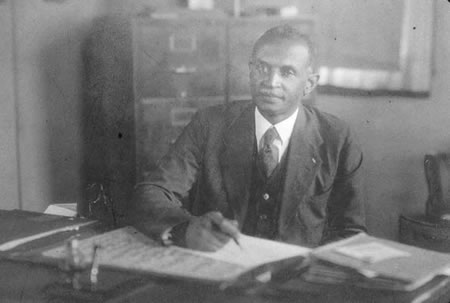

3 Nov. 1875–6 Oct. 1947

James Edward Shepard, college president, was the oldest of twelve children born in Raleigh to the Reverend Augustus and Hattie Whitted Shepard. He attended the public schools of Raleigh before entering Shaw University, where he received a degree in pharmacy in 1894. After working for one year in Danville, Va., Shepard opened a pharmacy in Durham. In 1898 he moved to Washington, D.C., and became comparer of deeds in the recorder's office. He returned to Raleigh to work from 1899 to 1905 as deputy collector of internal revenue for the federal government. From 1905 to 1909 he was a field superintendent of the International Sunday School Board for work among Black people.

In 1910 Shepard founded the National Religious Training School and Chatauqua in Durham. He served as the school's president and devoted most of his energies to its development. Though it had ten buildings and more than one hundred students by 1912, the school faced continual financial difficulties, so Shepard traveled widely soliciting funds. To satisfy its creditors in 1915 the facilities were auctioned off, but a personal donation from Mrs. Russell Sage of New York enabled the school to repurchase its property. The reorganized school became the National Training School and in 1923 the Durham State Normal School when the state assumed control. Under Shepard's continuing leadership the school in 1925 survived a major fire and became the North Carolina College for Negroes, the first state-supported liberal arts college for blacks in the nation. The General Assembly changed the name to the North Carolina College at Durham in 1947 and to North Carolina Central University in 1969.

Often compared to Booker T. Washington, Shepard rejected both confrontation and legislation to better race relations. He favored conciliation at the conference table and argued that "we cannot legislate hate out of the world or love into it." Shepard's approach won praise from the General Assembly in 1948: "this native born North Carolinian labored . . . with wisdom and foresight for the lasting betterment of his race and his state, not through agitation or ill-conceived demands, but through the advocacy of a practical, well considered and constant program of racial progress." More radical blacks, however, found Shepard's approach "disgusting uncletommism." One northern black critic charged that he "speaks not for the New Negro but for his little band of bandana wearers and them alone." Shepard articulated his views on racial affairs in a series of statewide radio broadcasts in the 1930s and 1940s and in speeches and writings for national audiences in which he supported and defended the progress of North Carolina.

A Republican in national politics, Shepard supported Democrats locally. He effectively presented his college's case before the state legislature. One political commentator declared in 1948, "He was regarded by many legislators the best politician ever to come before them. He probably got a larger percentage of his requests than anybody did and he generally aimed high." In 1945 the High Point Enterprise called him one of the state's ten more valuable citizens.

Shepard was a member of the Baptist church, a grand master of the Prince Hall Free and Accepted Masons of North Carolina, a grand patron of the Eastern Star, and a secretary of finances for the Knights of Pythias. He was president of the North Carolina Colored Teachers Association, the International Sunday School Convention, and the State Industrial Association of North Carolina; a trustee of Lincoln Hospital and Oxford Colored Orphanage; a director of Mechanics and Farmers Bank; and a member of the North Carolina Agricultural Society. Shepard received honorary degrees from Muskingham College (1912), Selma University (1913), Howard University (1925), and Shaw University (1945). He was the only black speaker at the World Sunday School Convention held in Rome in 1910.

On 7 Nov. 1895 Shepard married Mrs. Annie Day Robinson. They had two daughters, Annie Day and Marjorie. He died at his home in Durham of a cerebral hemorrhage and was buried in Beechwood Cemetery. The library at North Carolina College was named for Shepard in 1951, and a statue of him stands on the campus. The James E. Shepard Foundation was established to provide scholarships for worthy black students.