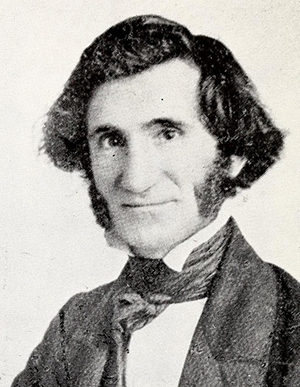

26 Oct. 1821–9 Nov. 1892

Solomon Sampson Satchwell, physician, was born in Beaufort County, the son of James, Sr., and Elizabeth Satchwell. He attended Wake Forest College from 1839 to 1841 and received an M.D. degree from New York University in 1850. Thereafter he practiced medicine in southeastern North Carolina until 1860, residing variously at Wilmington, Washington, and Long Branch. During 1860–61 he studied at the Sorbonne in Paris. Upon his return to North Carolina in 1861, Satchwell was made surgeon of the Twenty-fifth North Carolina Regiment and held the rank of major. In 1862 he became head surgeon of Confederate States Army General Hospital No. 2, at Wilson, where he remained until the end of the Civil War in April 1865. He then returned to private practice in Pender (until 1875, New Hanover) County, residing successively at Rocky Point and Burgaw.

Imbued with "the spirit of original thought and investigation" and the duty of the medical practitioner to communicate through appropriate channels the results of his research and practice, Satchwell early became a clinical investigator of the diseases prevalent in eastern North Carolina and, later, a promoter of a state medical journal. In 1852 he reported to the Medical Society of the State of North Carolina the results of his research on malaria, which he described as the leading cause of death in the South. Whoever should discover a means of combating malaria, he declared, would confer a greater boon on mankind than had Jenner in developing smallpox vaccination. Though he did not suspect the lowly mosquito as the culprit and subscribed to the miasmatic theory of the cause of malaria, Satchwell did recognize a positive correlation between the existence of bodies of stagnant water and the incidence of the disease. He believed therefore that proper sanitation and the practice of good personal hygiene offered possible means of limiting its spread.

Satchwell was, in fact, a pioneer in hygienic therapy—fresh air, sunshine, diet, and a minimum of drugs—and in public health. In commenting on one of the medical fads of the nineteenth century, namely attending springs and watering places as a means of treating disease, he noted that the "real instrumentality of good" in the practice was the "observance on such occasions of hygienic rules and regulations, and not the use of water." He consistently stressed the need for commonsense cleanliness in every aspect of medical practice and urged the development of a public health program in the state. Satchwell was a principal leader at every step in the creation of the State Board of Health, which he helped to organize at Greensboro on 21 May 1879. He was a member of the board from 1879 to 1884 and served as president from 1879 to 1881. In 1892 he was superintendent of public health for Pender County.

As a leading member of the Medical Society of North Carolina (organized in 1849) from 1850 until his death, Satchwell labored diligently to improve the status of the medical profession in North Carolina, serving as the society's secretary from 1854 to 1856 and as its president in 1868. He helped to promote the establishment in 1858 of the Medical Journal of North Carolina, which the society published until 1861, and served as associate editor in 1860 and 1861. Satchwell was a foremost leader in urging upon the legislature the authorization (1859) of the State Board of Medical Examiners, which the medical society was empowered to organize and administer. Satchwell was a member of the board from 1866 to 1872 and secretary in 1872. In 1873 he played a prominent role in the society's creation of the Board of Censors for the purpose of policing the practice of medicine in the state and adjudicating disputes arising out of practice by the society's members. This move did much to improve intraprofessional comity as well as the relationship of the medical profession with the public. As secretary of the Board of Medical Examiners, Satchwell in 1872 presented to the medical society the credentials of Dr. Susan Dimock, the first female native of the state to receive the M.D. degree. As a young girl growing up in Washington, N.C., Dr. Dimock had once lived across the street from Satchwell, her family's doctor, and he had encouraged her interest in medicine. She was graduated from the medical school of the University of Zurich, Switzerland, in 1871 and was engaged in specialized study in Paris in 1872. Following a fierce debate on the propriety of women's entering the medical profession, the Medical Society of North Carolina admitted her to honorary membership as a compromise. Dr. Dimock never practiced medicine in North Carolina, however. She died on 8 May 1875 after a brief but busy practice in Boston, Mass., when the ship on which she was traveling to Europe was wrecked on a reef near the Scilly Isles, twenty-five miles off the coast of Cornwall, England.

Satchwell had considerable reputation as an orator, both among his colleagues and with the public. A man of exceptional cultural, practical, and intellectual attainments, he was called upon to speak before a variety of audiences on a wide range of topics, many of which had little to do with medicine. His published addresses and papers show that he possessed an excellent command of the English language.

Satchwell was married twice. His first wife, whom he wed in 1865 or earlier, died no later than 1875. By this marriage he had three sons—James M., Solomon S., and Paul D.—and one daughter—M. B. (Only her initials are given in the 1880 census.) At some time after 1 June 1880, Satchwell married a daughter of H. F. Bell, of nearby Rocky Point. She died at Burgaw on 17 Jan. 1892, leaving a young son, and was buried according to the rites of the Methodist church, of which she was a member, in the family cemetery on her father's farm. Less than ten months later Satchwell died at Burgaw of typhoid fever and was buried in Oakdale Cemetery, Wilmington.