10 Sept. 1778–23 Jan. 1843

Joshua Lawrence, Baptist minister, farmer, and pamphleteer, was born in Edgecombe County, one of several children of John and Absilla Bell Lawrence. His father died when he was about seventeen, leaving him a plantation on the west side of Fishing Creek about a mile and a half above its confluence with the Tar River. There he lived for the rest of his life; the shell of the house he built around 1810 was still standing in 1970.

Lawrence received little formal schooling and for several years after his father's death seems to have indulged a propensity for profligacy, though not to the extent of wasting his property; industry and frugality characterized his life, even as a tumultuous teenager. The precise nature of his alleged depravity is not known, but it must be remembered that card playing and dancing were in that day considered mortal sins by the fundamentalist sects. Whatever his transgressions, he repented after a few years and joined the Baptist church at Fishing Creek (later Lawrence's Meeting House), where he was baptized by Elder Nathan Gilbert. In 1801 he was ordained to the ministry by Elders Lemuel Burkitt and Jesse Read and succeeded Gilbert as pastor of the Falls of Tar River Church.

His first efforts at preaching were awkward as he could scarcely read, but his natural gifts as an orator, combined with an application to self-education and a retentive memory, soon overcame that handicap. He became, according to contemporary accounts, a forceful and eloquent preacher, possessed of a pleasant voice, a great flow of words, and a commanding appearance. It was said that he could sing, pray, and preach sermons while asleep, without any knowledge of it himself. Within two years, over one hundred persons were baptized by him and added to his church.

In 1803 Lawrence was sent by his church as a delegate to the Kehukee Association, which in that year saw the first step within that association of churches toward the missionary cause. Dissension over that and other sectarian differences grew for the next twenty-four years, resulting finally in total disunion.

In 1817 Lawrence began to hold monthly meetings in Tarboro and in 1819, with the help of Elders Martin Ross, Thomas Billings, and Thomas Meredith, he succeeded in constituting the Tarboro Baptist Church, of which he was the first regular minister. He remained in that post until 1829, when the church was split, thereafter continuing as minister of the Old School or Primitive Baptist church until his death.

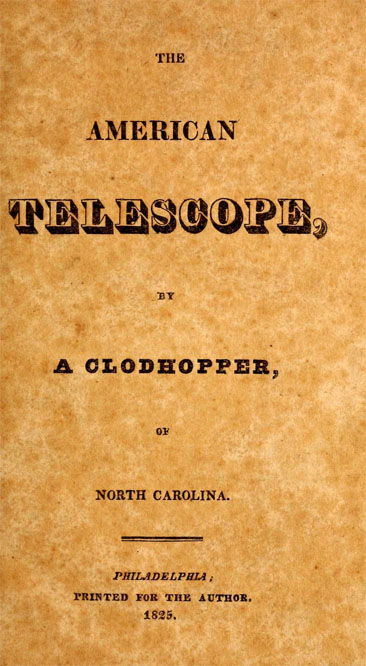

During the intervening years, as the controversy within the Kehukee Association grew more intense, Lawrence assumed the leadership of the opposition to the Missionary Baptists. He inveighed against them from the pulpit with all the considerable power of his oratory and, beginning in 1825, he attacked them in print. The American Telescope by "a Clodhopper of North Carolina," printed in Philadelphia in that year, was the first of the pamphlets that he produced intermittently throughout his career expressing forthrightly his religious and political opinions. He opposed the Missionary Baptists and, for that matter, all other churches, for what he called "craft," concluding in one of his sermons: "We shall next notice the established Christian religion, turned from its simplicity and virgin beauty into a craft." He believed that the ministry was God's calling and therefore not to be used for material gain. As a successful farmer Lawrence could afford to offer his ministry free of charge, but strict adherence to this principle worked a real hardship on less affluent ministers. A strong believer in religious and civil liberty, he also denounced all meddling in politics by any church. Among other pamphlets, he was the author of The North Carolina Whig's Apology (1830), A Basket of Fragments for the Children (1833), and The Mouse Trying to Gnaw out of the Catholic Trap (n.d.).

It was Lawrence who wrote the "Declaration of Principles" that the Kehukee Association submitted to the churches of the association in 1826 and considered during its session the next year. By this declaration, the association agreed to "Discard all Missionary Societies, Bible Societies and Theological Seminaries." It objected to seminaries not because it disapproved of the dissemination of knowledge but because "preaching would thereby become a lucrative employment like the law, physic, etc."

The vehemence with which Lawrence expressed his views evoked responses in kind, culminating in threats against his life. Whether there was real substance to these warnings is not known, but the fact that they were made indicates the depth of feeling engendered by the controversy. In 1829, on account of the threats, he withdrew from the pulpit for several months, during which time it was filled by Elder P. W. Dowd, who came out so strongly for the missionary cause that the church was divided into two hostile factions. When Lawrence was invited back by his supporters, Dowd seized the keys to the new meetinghouse. Lawrence then took the minute books and, followed by a majority of the congregation, went to the old meetinghouse, where they expelled from membership all who had remained with Dowd.

Lawrence was by far the most forceful and articulate apologist of the Primitive Baptists; without his leadership, they fell into decline and, except for a brief resurgence in the late nineteenth century, remained a minor sect. Despite failing health during the last several years of his life, Lawrence continued to preach at the old meetinghouse at Fishing Creek until a few months before his death. He died after a three months' illness and was buried on his home place. After his wife's death in 1851, identical stones were erected to mark their graves; on his, the year of his death was erroneously given as 1842. Moreover, the tombstone cutter had gratuitously added the title "Rev." before his name on both stones. Knowing how deeply Lawrence felt that such an appellation should be reserved for God and preempted by no man, his family chiseled those three letters from the stones. The controversial character of the man inspired the story that vandals had done it, but the neat, though amateurish, nature of the work belies that tale. These stones, the only ones in the family graveyard, were moved in 1970 to the Primitive Baptist Churchyard in Tarboro.

In about 1800 Lawrence married Mary Knight, daughter of Peter and Ann Bell Knight. They had thirteen children, seven of whom survived him: John, Josiah, M.D., Louisiana, Joshua L., Bennett B., Pherebe, and Thomas David. Of those who predeceased him, the name of only one, Lemuel, is known.