13 Sept. 1902–15 Aug. 1976

John Tate Lanning, historian, was born in Linwood, Davidson County, the son of Baxter Franklin and Carrie Aletha Smith Lanning. After graduation from Trinity College (later Duke University) in 1924, he studied under the eminent Hispanic-American historian Herbert Bolton at the University of California at Berkeley, receiving an M.A. in 1925 and a Ph.D. in 1928. Returning to Duke University as an instructor in 1927, he rose to the rank of professor in 1942 and was named James B. Duke Professor of History in 1961, the highest award given by the university. He retired from teaching in 1972 but continued his research and writing until his death.

In 1932 Lanning married Elizabeth Baxter Williams, the daughter of Judge Wade H. Williams of Charlotte and a graduate of Duke in 1931. Prominent in many civic activities, Elizabeth Lanning became the first woman elected to political office in Durham when she served as a member (1951–57) and then chairman (1957–58) of the Durham County Board of Education. They had three children: John Tate, Jr., Lucy Hampton, and Thomas Pinckney.

Lanning's early work in southeastern colonial history, especially on Spanish influence in the area, was embodied in The Spanish Missions of Georgia (1935) and The Diplomatic History of Georgia (1936) as well as several later publications. This early interest soon grew into a broader concern with the entire field of colonial Hispanic-American cultural and social life, which formed the framework of a distinguished and productive career, including eleven books and numerous articles in major historical periodicals. From extensive research in the archives of Great Britain, Spain, and Latin America, Lanning laid the foundations of a revolution in the historiography of the intellectual history of the Spanish colonies, not only by exploring areas little touched by previous historians, but also by challenging the long-held view that Spanish colonial intellectual life had been hostile to learning during the Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Besides his Academic Culture in the Spanish Colonies (1940), two articles written in the same period remain milestones in Hispanic-American historical studies: "Research Possibilities in the Cultural History of Spain in America" (Hispanic American Historical Review, 1936) and "The Reception of the Enlightenment in America" (A. P. Whitaker, ed., Latin America and the Enlightenment, 1942).

The summit of Lanning's scholarly work came with the publication of The University in the Kingdom of Guatemala (1955) and The Eighteenth-Century Enlightenment in the University of San Carlos de Guatemala (1956), which won, respectively, the Carnegie Revolving Fund Prize and the Herbert Bolton Memorial Prize of the American Historical Association. These two studies of an institution that granted 2,500 degrees between 1625 and 1821 analyzed virtually every facet of its academic and administrative life. More significantly, through a ground-breaking analysis of student theses, Lanning developed a tool for tracing the changes in thought and ideas in an academic institution. He thereby revealed the existence of an intellectual dynamism that kept the University of Guatemala in the forefront of Enlightenment ideas in philosophy, science, and medicine. The books were praised not only for their substantive content but also for their graceful style and lucidity. In 1974, two years after his retirement, he published Pedro de la Torre: Doctor to Conquerors, an offshoot of a large-scale study of the medical profession in the Spanish Empire (completed in draft form shortly before his death). In Pedro de la Torre, Lanning demonstrated once more a complete command of sources as well as interpretative and stylistic subtlety.

Lanning was concerned as much with the advancement of scholarship among his colleagues as with his own. His tenure as managing editor of the Hispanic American Historical Review from 1939 to 1945 (following upon four years as associate managing editor) saw an expansion of both format and scope as well as increased circulation among scholars in Latin America. He was also a member of the advisory editorial boards of Americas and the Latin American Review. A close interest in a broad range of research pursued by his colleagues at Duke is attested by his long membership on the Research Council (secretary, 1949–61; chairman, 1961–66). He was also active in the American Historical Association.

Lanning believed that a research library constituted the "irreplaceable heart," free of the coils of academic partisanship, of an institution of higher education. The fruit of this belief was the Hispanic Collection in the Duke University Library, which he, and like-minded colleagues from both his own and other fields, began to assemble in the 1920s. It later totaled over 225,000 volumes. His personal collection in Hispanic-American history (now at the University of Missouri in St. Louis) was also an important one: among more than 3,500 volumes were over 200 bound volumes of manuscript copies of original documents, mostly from the National Archives of Mexico and the Archives of the Indies in Seville.

The dedication Lanning brought to historical research and writing was reflected in his teaching. He demanded of the five thousand students whom he taught in his long career nothing less than the very best they could produce, and he was not inclined to be patient with those who did not do so. For his graduate students he felt a special sense of responsibility, and those who accepted his rigorous adherence to standards were the beneficiaries of his remarkable gift for combining scholarly training and guidance with patience, understanding, and, when needed, a timely push and admonition.

The list of honors earned by Lanning began in 1930 with one of the first Guggenheim Foundation Fellowships awarded, followed by grants from other distinguished agencies. Besides his election to various Latin American historical societies, he was offered and undertook numerous visiting lectureships in the United States and Latin America. Another mark of the esteem he enjoyed within the profession came in 1958, when he was given the prestigious Serra Award of the Americas by the Academy of American Franciscan History. In his acceptance speech, Lanning summed up his professional credo when he praised the work of the scholar who was able to "add an atom of clarity to the confusion of life or subtract a particle from the antagonism of peoples."

As these remarks indicate, Lanning pursued his discipline with a profound sense of mission, both in its practice and in the ultimate goals he intended his work to serve. Formal yet courteous in bearing, literate in the widest sense of the word, with an uncompromising devotion to high standards of accuracy, balance, and fairness, tempered by a wise (and at times humorously ironical) insight into humankind both past and present, Lanning was, above all, a "scholar's scholar."

One of the final tributes, and one closest to his heart, came in 1973, when his former students established an endowment fund in his name for the Duke University Library. Lanning was also one of three professors honored in similar fashion three years earlier by the P. H. Hanes Foundation.

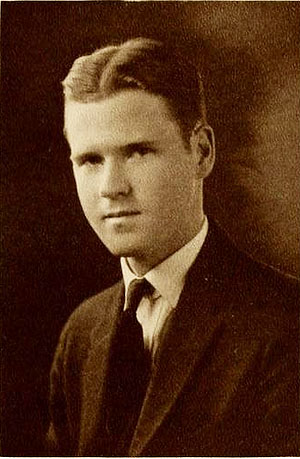

Lanning was buried in Sandy Creek Cemetery in Davidson County. There are two portraits in the possession of his family.