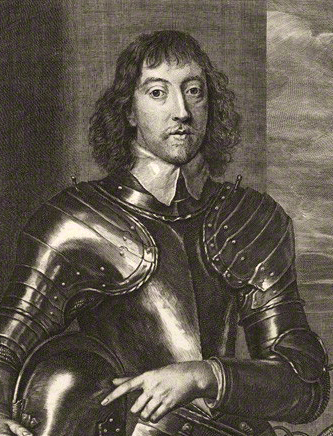

15 Aug. 1608–17 Apr. 1652

Henry Frederick Howard, third Earl of Arundel and Surrey, Earl Marshal of England, and proprietor of Carolana, was the second but oldest surviving son of Thomas, second Earl of Arundel, and his wife, Lady Althea Talbot, daughter and ultimately sole heiress of Gilbert, seventh Earl of Shrewsbury. His great-grandfather was Thomas Howard, fourth Duke of Norfolk, who conspired against Queen Elizabeth with Mary, Queen of Scots, and was beheaded in 1572 for his part in the Ridolfi Plot. With the fourth duke's attainder, the ducal title and properties were lost to the Howard family for three generations. However, the fourth duke's son, Philip (1557–95), inherited—in right of his mother—the title of Earl of Arundel. This title eventually reached Henry Frederick through his father, Thomas (1585–1646), the second Earl of Arundel.

Throughout much of his life, Howard had only the courtesy title of Lord Maltravers. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1628 and continued to serve in Commons until he was summoned to the House of Lords on 21 Mar. 1640 as Baron Mowbray and Maltravers, by which title he was known until the death of his father.

Howard's first notoriety resulted from his youthful marriage in 1626 to Lady Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of Esmé, Duke of Lennox, and ward of King Charles. This marriage infuriated the king who had arranged for Lady Stuart's marriage to Lord Lorne, oldest son of the Earl of Argyle. For a period, Howard's father was confined in the Tower of London and the couple was placed in the custody of the Archbishop of Canterbury. After intervention by the House of Lords, the king relented and all were released.

As son and principal heir of the premier earl of England, Howard enjoyed numerous appointments and honors. From 1633 to 1639 he served as joint lord-lieutenant of Northumberland and Westmoreland. In 1633 he was appointed a commissioner to exercise ecclesiastical jurisdiction in England and Wales, in 1634 he was made a privy councillor of Ireland, and in 1636 he was named joint lord-lieutenant of Sussex and Surrey. In the latter year he was also designated vice-admiral of Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, and Isle of Ely.

These were but a few of the honors bestowed upon Howard in a period in which he was becoming increasingly involved in English colonial and overseas affairs. His interest in these matters probably originated with his father, the second earl, who had been one of the supporters of Sir Walter Raleigh's Guiana voyage of 1617, a member of the Virginia Company and the Council for New England, one of the leading adventurers in a plan to establish a plantation on the Amazon River under Captain Roger North, and in 1634 a member of the Laud Commission.

While still in his twenties, Howard became involved in overseas activities that soon rivaled those of his father. In 1632, he was received in the Council for New England as a councillor and patentee and along with others received grants of territory from that body. Unfortunately these deeds of feoffment were not confirmed by the Crown and were without legal validity. As late as 1638, however, Howard requested of the council "a degree more in latitude and longitude to be added to his portion of lands."

Howard joined with others in a plan to establish a West India Company in 1637. The plan called for an attack on Spain through its West Indian possessions. Some fit port in the West Indies was to be seized as a base of operations against the Spanish islands and as a haven for retreat. The investors in the West India Company planned to divide all spoils from these activities among themselves. In 1638 Howard was given a license for twenty-one years to stamp farthing tokens for distribution in all of the English colonies except Maryland. A colony was to be furnished as many of these farthings as were needed in exchange for commodities vendible in England. Many would have agreed with one seventeenth-century observer that this "Son & heir to the Ld Arundale . . . had a wonderful Inclination & a great Sagacity in promoting the plantation of Northern America and some of the Islands thereunto Adjacent."

Howard's interest in colonial promotion and settlement led him to use his influence sometime before 1637 to obtain a letter from King Charles to the governor and Council of Virginia ordering them to set out a county in the southern part of that colony for him. This letter miscarried in some manner, and on 11 Apr. 1637 another royal letter was sent by Charles to his Virginia government once more instructing that colony's officials to assign Howard "such a competent tract of land in the Southern part of that country as may bear the name of a county and be called the county of Norfolk." The county was to be awarded on conditions that would serve the good of the colony, and Howard was to be granted powers and privileges within the county that befitted "a person of his quality." A yearly rent of twenty shillings was to be reserved for the Crown.

Acting on these instructions from the king, Governor John Harvey and the Virginia Council issued a patent to Howard for the County of Norfolk on 22 Jan. 1637/38. The county was to extend southward from the branches of the Nansemond (now Suffolk) to 35° north latitude or about as far south as the mouth of the Neuse River. It was to extend east and west 1° in longitude on either side of the Nansemond River. The Virginia authorities had rather cleverly drawn Howard's county so that much of it lay within the area of the proprietary province of Carolana, which had been granted Sir Robert Heath in 1629 by King Charles and which extended from 36° to 31° along the coast. The Virginia patent required Howard to people the county within seven years and gave him certain severely circumscribed powers and privileges within the county.

In the end this patent proved of little interest or importance to Howard, for one month before the Virginia government reluctantly issued him a patent to the County of Norfolk, he was able to purchase the princely domain of Carolana from its proprietor, Sir Robert Heath. On 2 Dec. 1637, with the king's entire approbation, Heath, for an unknown sum, conveyed his title to Carolana to Howard. The yet unsettled Carolana extended from 36° to 31° north latitude and from the Atlantic westward to the South Seas. The charter assigned to the proprietor full title to this vast area and the power necessary to govern any settlement that might be made there.

Howard moved rapidly to establish a settlement and government in Carolana. On 2 Aug. 1638 he commissioned Captain Henry Hawley, then deputy governor of Barbados, to settle the southern part of the province, awarding him the title of lieutenant general of Carolana and 10,000 acres of land in that province. At the same time he apparently commissioned a Captain Henry Hartwell to settle the northern part of the province. Whatever his precise arrangements with Howard, Captain Hawley did not personally attempt to lead a colony into Carolana. Instead he appointed his brother, Captain William Hawley, to be deputy governor of Carolana and sent him to Virginia to organize an expedition to establish a colony to the south in Carolana. In April 1640, the Virginia Council under spur of a letter from the Crown granted leave for Carolana to be colonized by an expedition of "one hundred persons from Virginia, 'freemen being single, and disengaged to debt.'"

There is no evidence that Hawley ever led an expedition into Carolana or that Howard or any of his agents ever actually got a colony into that province. Although many decades later there were those who maintained that he had "at great expense planted several parts of the said country," there is no evidence to support such contentions. Certainly no lasting settlement was ever made. Still Howard did not lose interest in the project. In the summer of 1638, when it appeared that the Virginia charter would be restored, he joined with Lord Baltimore in insisting that any new charter contain a clause securing their provinces "from any prejudice or inconvenience that might accrue to them." In all probability the mounting constitutional crisis in England distracted Howard and left him with little time to develop Carolana. As the difficulties increased in England, Howard took a strong and unyielding stand at the side of the king. He was one of the earlier signers of the "Protestation" in May 1641 by which he bound himself to "maintain and defend" the Protestant faith, and he took an active part in all military operations. After the capture of Banbury, he received the honorary degree of master of arts at Oxford in November 1642. Subsequently, he became joint commissioner for the defense of the county, city, and university. The illness of his father at Padua, Italy, took him from the country for months, and his father's death on 4 Oct. 1646 brought him the title of Earl of Arundel and Earl Marshal of England. When he returned home, he found that his property had been seized, but by vote of Parliament he was permitted to redeem his estates for a payment of £6,000.

In 1649, as the Civil War came to an end, notices began to appear in the London newspapers announcing that an expedition was preparing to sail shortly for Carolana and that a governor had been named. In the following year, a pamphlet was published extolling the virtues of Carolana and announcing that settlers were preparing to go out to that province. Meanwhile a map was published to show prospective colonists the precise location of Carolana. Howard's role in developing these plans for a colony is uncertain, but it seems unlikely that they could have been developed without his full knowledge and consent. Whatever may have been his part in this enterprise, it did not succeed. No colony sailed from England for Carolana.

His last years were devoted to efforts to break his father's will. This led to a bitter and prolonged fight with his mother, who opposed him. This role of the ingrate son has colored much of the subsequent writing about him. He died at age forty-four, two years before the death of his mother.

Howard's marriage to Lady Elizabeth Stuart produced nine sons and three daughters. His oldest son and heir, Thomas (1627–77), began to show signs of insanity while living with his grandfather in Italy in the 1640s. His "hopeless insanity" gradually worsened and "though he lingered many years, he was no more than a cipher." Thomas's brother, Henry, managed his affairs and in 1660 was able to secure the restoration of the title and honors of the dukedom of Norfolk to the Howard family after nearly ninety years. On the death of Thomas, Henry became the second son of Henry Frederick to succeed to the dukedom of Norfolk.