24 Mar. 1865–26 Sept. 1930

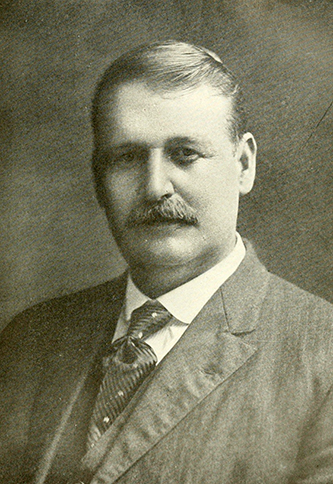

William Cicero Hammer, lawyer, editor, and congressman, was born in Randolph County four miles southwest of Asheboro. His parents were William Clark and Hannah Jane Burrows Hammer. The son and grandson of ministers of the Methodist Protestant church, he became a charter member of the First Methodist Protestant Church of Asheboro, as well as a member of the Asheboro Rotary Club and of the Masonic and Junior Orders. He was educated in the public schools of Randolph County before attending Yadkin Institute, Western Maryland College, and The University of North Carolina. Admitted to the bar in 1891, he practiced law as a partner in the firm of Hammer and Wilson in Asheboro.

Before beginning a political career, Hammer taught in the public schools of Randolph and Davidson counties. His first public position was as a member of the Asheboro City Council; he also served as mayor of Asheboro for one term. In the years 1891–95 and 1899–1901 he was superintendent of public instruction in Randolph County. Early in 1902 Governor Charles B. Aycock appointed Hammer as solicitor in the Superior Court of what was then the Fifteenth Judicial District to fill the vacancy left by the death of Wiley Rush. In the fall of that year Hammer was elected to the office. In 1914, President Woodrow Wilson appointed him U.S. attorney for the Western North Carolina District; he served until September 1920, when he received the Democratic nomination to the House of Representatives from the Seventh North Carolina District.

The record of Hammer's congressional career, which spanned the decade 1920–30, was noteworthy in several respects. Among his priorities was legislation to end adult illiteracy and to expand education throughout the nation. His attitude towards education became evident when he supported the Towner-Sterling Educational Bill, one that would not only create a department of education but also help to eliminate illiteracy, promote physical education, and attempt to equalize educational opportunities. Hammer also consistently strove for farm relief. A supporter of the McNary-Haugen Act, he earnestly believed that this bill "would bring about real orderly marketing of farm products, so that the farmers themselves would get the full benefits therefrom." Hammer was the only member of the North Carolina delegation who voted consistently for the McNary-Haugen farm bill. In addition to educational opportunities and farm relief, he favored the building of better roads even when this position was unpopular. To assure getting the best for his own county, he accompanied the surveyors when the roads were being laid out.

In the 1920s, sentiment was divided on the issue of child labor regulations and restrictions. In a speech before the House, Representative Hammer advocated a child labor law; thus he urged "cooperation with the states for the protection of child life through infancy and in the prohibition of child labor." Nevertheless, no federal child labor law was enacted until 1938.

In Congress, Hammer served on the Judiciary, Patents, Pensions, Expenditures, and Executive committees. His chief work was conducted in the District of Columbia Committee, where he devoted much attention to educational affairs in Washington. Yet he still found the time to familiarize himself with proposals to mitigate the ills of agriculture. In the Judiciary Committee Hammer dealt with impeachment cases and worked out the details of the administrative program for law enforcement as it related to prohibition, including the preparation of a provision for the transfer of enforcement from the Treasury Department to the Department of Justice.

For more than forty years Hammer owned and edited the Asheboro Courier, which was widely read in Randolph County. Before he bought the paper in 1891, the Courier had been known as the Randolph Regulator, which dated back to 1876 and had been operated by M. S. Robins. Prior to entering politics, Hammer had ample time for his newspaper work; even after becoming the Seventh District representative, he maintained close ties with the editors in North Carolina. He served the North Carolina Press Association as president and in other official capacities. But gradually his wife, Minnie Hancock Hammer, took over his business affairs and assumed the management of the newspaper. Mrs. Hammer also helped him in other ways. On 4 July 1930, when the congressman was too ill to fill his speaking engagement at Guilford Battleground, his wife delivered the speech for him. After Hammer's death, she was invited to fill his seat in Congress for the remainder of the term but declined because of home, church, and business obligations. She continued to operate the Asheboro Courier until 1938, when the newspaper was sold. Congressman and Mrs. Hammer were the parents of a daughter, Harriette Lee.