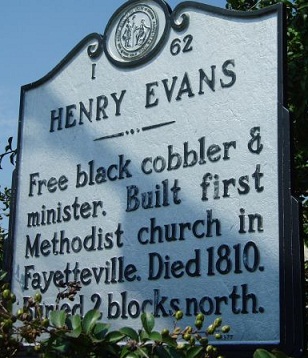

ca. 1760–17 Sept. 1810

Henry Evans, popular Black preacher, was credited with being "the father of the Methodist Church, white and Black, in Fayetteville, and the best preacher of his time in that quarter," according to Bishop William Capers, who, as a youthful probationer in the ministry, was appointed to Fayetteville a few months before Evans's death. Evans was the son of free Black Americans from Virginia, a shoemaker by trade, and a licensed Methodist preacher. En route to Charleston, S.C., about 1780, he stopped in Fayetteville. Hoping to improve the lives of enslaved people in the area, he decided to stay and preach. When town authorities forbade such "agitation," he was obliged to go into the surrounding sandhills to hold services, changing from place to place to escape mob violence. In time, however, white enslavers began to recognize an improvement in the manners and morals of his listeners, and eventually the leaders of the Fayetteville community allowed him to preach in town.

Sometime before 1800, a rough building was put up to house Evans's congregation. Soon white visitors filled the seats reserved for them and began to fill the spaces designed for Black congregants as well, and after a few years sheds had to be built onto the sides to accommodate the crowds. Capers records Evans "was so remarkable, as to have become the greatest curiosity of the town; insomuch that distinguished visitors hardly felt that they might pass a Sunday in Fayetteville without hearing him preach."

Evans's church was visited on several occasions by Bishop Francis Asbury, who, in his Journal (14 Jan. 1805), called it the "African meeting house." It was built on the site of the present-day Evans Metropolitan A.M.E. Zion Church. Evans lived in a room at the back of the chancel and continued to stay there after his health declined and he, around 1806, turned the congregation over to preachers appointed by Asbury. In a unique will, dated 9 Dec. 1809, he bequeathed the part of the building and lot used for church purposes to the Methodist Episcopal church, but provided that his residence and the rest of the lot were to go to the church only at the death of his widow.

Capers, in his brief acquaintance with Evans, noted that he was unusually "conversant with Scripture," that his conversation was "instructive as to the things of God," and that he seemed "deeply impressed with the responsibility of his position." Capers recorded a moving account of Evans's last words to the congregation and his funeral:

"On the Sunday before his death . . . the little door between his humble shed and the chancel where I stood was opened, and the dying man entered for a last farewell to his people. He was almost too feeble to stand at all, but supporting himself by the railing of the chancel, he said, 'I have come to say my last word to you. It is this: None but Christ. Three times I have had my life in jeopardy for preaching the gospel to you. Three times I have broken the ice on the edge of the water and swum across the Cape Fear [River] to preach the gospel to you. And now, if in my last hour I could trust to that, or to any thing else but Christ crucified, for my salvation, all should be lost, and my soul perish for ever.' A noble testimony! Worthy, not of Evans only, but St. Paul. His funeral at the church was attended by a greater concourse of persons than had been seen on any funeral occasion before. The whole community appeared to mourn his death, and the universal feeling seemed to be that in honoring the memory of Henry Evans we were paying a tribute to virtue and religion. He was buried under the chancel of the church of which he had been in so remarkable a manner the founder."