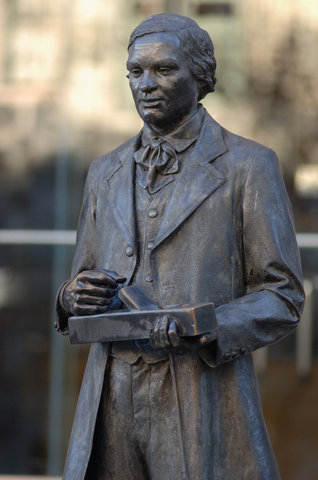

ca. 1801–ca. 1861

Thomas Day, cabinetmaker, was the son of Morning S. Day (b. ca. 1766 in Virginia), but his father is unknown. Thomas Day married Aquilla Wilson (b. ca. 1806) of Halifax County, Va., in Halifax on 7 Jan. 1830. Their children were Mary Ann (b. ca. 1831), Devereaux (b. ca. 1833), Thomas, Jr. (b. ca. 1837), and possibly another daughter A. [Aquilla?] (b. ca. 1835). All children were presumably born in Milton, where Day lived from about 1823 until 1861. A free black person, Day's place of birth is listed in census records as Virginia and, judging from his age as listed in those records, his date of birth was 1801. Much information concerning Day is based on oral history and tradition. According to various reports, he was born on a farm outside Milton, he was born in Virginia, he was Portuguese, he was born in the West Indies, or he was born in Guilford County. Because Milton is on the Virginia border and the census lists Day's and his mother's place of birth as Virginia, it is likely that he was born near Milton, in either Halifax County or Pittsylvania County, Va.

On November 27, 1851, Day wrote his daughter: "I am perfectly satisfied as regards Milton—I came here to stay four years & am here 7 times four I love the place no better nor worse than [the] first day I came into it." It can be inferred from this that Day arrived in Milton about 1823. He was certainly there in 1827 when he appeared in the tax records as a property owner. In the same year he advertised in the March 1, 1827 Milton Gazette & Roanoke Advertiser : "Thomas Day, Cabinet Maker, returns his thanks for the patronage he has received, and wishes to inform his friends and the public that he has on hand, and intends keeping, a handsome supply of mahogany, walnut, and stained furniture, the most fashionable and common bedsteads, &c. which he would be glad to sell very low. All orders in his line, in repairing, varnishing &c., will be thankfully received and punctually attended to."

When Day arrived in Milton he may have already trained as a cabinetmaker, though he would have been only twenty-two. Within four years he had funds sufficient to purchase property and go into business for himself. Among the stories involving his childhood and training as a cabinetmaker, one tradition maintains that he showed marked ability as a child, copying to scale pieces of furniture that he saw in homes he visited with his parents. It is possible that he spent his first few years in Milton in the shop of someone else. There were a number of other Milton cabinetmakers or carpenters with whom he could have been apprenticed, but by January 1827, when he placed the newspaper advertisement, Day already had a shop, customers, and available stock.

In 1830, when Day crossed the border from North Carolina into Virginia, married Aquilla Wilson, also a free black person, and attempted to return with her to Milton, he was prohibited from doing so by North Carolina law, which in 1827 had halted the immigration of free black people into the state. Day ultimately appealed to the General Assembly, and late in 1830 a special act was passed to allow his wife to enter the state. In a petition to the legislature on his behalf, some sixty-one white citizens of the area supported the special act for Day, noting that he was "a free man of colour, an inhabitant of this town, cabinet maker by trade, a first rate workman, a remarkably sober, steady and industrious man, a high-minded, good and valuable citizen, possessing a handsome property in this town." Attached to the petition was a letter from R. M. Saunders, a former speaker of the North Carolina House of Commons and member of Congress, who in 1828 had been elected attorney general of North Carolina. Saunders wrote "I have known Thomas Day . . . for several years and am free to say that I consider him a free man of color, of very fair character—an excellent mechanic, industrious, honest and sober in his habits—and in the event of any disturbance amongst the Blacks, I should rely with confidence upon a disclosure from him—as he is the owner of slaves as well as of real estate."

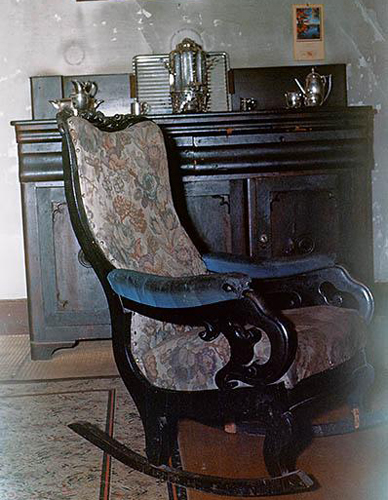

Day was indeed in the unusual position of the pre-Civil War free black person who not only enslaved people, but who also trained white apprentices in his cabinetmaker's shop. He also sat on the main floor of the predominantly white Milton Presbyterian Church in a front bench, one of the pews that he had carved for the church, built about 1837. He and his wife were accepted into full membership in 1841. Over the years Day purchased as his residence and place of business—he added a brick addition to contain his workshops—one of the most important structures in Milton, the Union or Yellow Tavern. He became a major stockholder in the local branch of the North Carolina Bank and purchased additional land outside the town.

The cabinetmaker sent his children to Wilbraham Academy (now Wesleyan University) in Connecticut. At least one daughter studied music in Salem, where she boarded with a Moravian family. She is said to have studied later in England. Day himself was certainly well educated, writing literate letters to his children and clients and sometimes evoking philosophical arguments or quoting from classical writers.

Day suffered financial reverses in 1858, but was able to recover and remain in business with the assistance of his business associate Dabney Terry, a white house-builder and contractor in Milton. Day disappeared from public records in 1861, though his shop was operated by his son, Thomas, Jr., for at least ten more years. Day is believed to have been buried on his farm outside Milton where a grave is marked by a cairn.

What is most unusual about Day, a free black person in the pre-Civil War South, is not that he established himself as a cabinetmaker at a relatively early age, but that for almost forty years he maintained his business, producing furniture and architectural detail for a number of important clients. His work seems never to have been out of favor, nor to have been lost at any period. Over the years articles about Day or his work regularly appeared in newspapers of the Virginia and North Carolina Piedmont, especially in Caswell County where Milton is located. Here both his cabinetwork and architectural interiors have been pointed to with pride. Houses with mantels by Tom Day, as he is known locally, are well known, and Day interiors appear in many area houses built during the county's boom era between 1830 and 1860, when bright leaf tobacco culture brought great wealth to the county. Many of these houses also contain furniture produced by Day.

Among Day's clients were Attorney General Saunders (later minister to Spain) and Governor David Settle Reid (later a senator from Rockingham County). According to tradition, Day carved furniture for the North Carolina governor's mansion but it was rejected because of its cost. He did raffle furniture in Raleigh, possibly the pieces carved for the governor's mansion. During the 1840s he worked on the interiors of the two society halls at The University of North Carolina, entering into correspondence about the work with D. L. Swain, then university president. He carved furniture and interiors for the Milton Presbyterian Church and the Milton Baptist Church and for a large number of other important as well as quite ordinary clients. A surprising number of bills, letters, diary entries, and other documents concerning his production of furniture and architectural detail survive, many still with the objects to which they relate. Some of his architectural work—including the William Long house in 1856—was accomplished in partnership with Dabney Terry, the Milton builder who came to Day's financial rescue in 1858.

No signature has yet been discovered on any piece of furniture or on the architectural detail that Day produced. His earliest work seems to have been simple, academic, and pure. Some of his Gothic Revival output was more innovative and expressive than the earlier work, but it was with Greek Revival and Italianate architectural detail and Empire style furniture that he reached his stride. Such output is bold, sometimes expressing African themes or Afro-American impressions of classical themes, sometimes closely approximating the work of Belter and other well-known cabinetmakers of the mid-nineteenth century. He frequently used three-dimensional motifs, evidently in an awareness of the changing aspects that light and shadow allowed with such work.

Much of Day's work seems to have been produced for a given space within a dwelling or public building, though he also carried pre-finished stock in his shop and had catalogues of his own designs from which clients could choose. At least two volumes of his designs survived until 1928, when they were destroyed in a house fire in Raleigh.

Examples of Day's work have recently been included in a number of exhibitions at well-known museums, as well as in several publications on black artisans. The only special collection of his work is in the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh, although the Greensboro Historical Museum also owns a number of Day pieces. The Yellow Tavern, the cabinetmaker's home in Milton, is on the National Register of Historic Places and is a National Registered Landmark to honor the cabinetmaker and his important work in pre-Civil War America.