Published with permission. For personal educational use and not for further distribution.

December 30, 1929-April 23, 1982

Arthur Stafford Alford, nicknamed “Ott,” was a career educator who served as superintendent of Pitt County Schools from 1965 to 1982 and was a leader in the desegregation in Pitt County Schools.

Born in Laurinburg, North Carolina, Alford graduated from Laurinburg’s public schools in 1948 and went on to study at East Carolina University. During his time at ECU, Alford married Betty Jacobs in 1950. He graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Physical Education and Mathematics in 1952 and then conferred a Masters degree in 1954.

“Ott” Alford began his career as an educator as a teacher at Chicod School in 1952, then became the school’s principal in 1953. Alford served as the supervisor of elementary schools for Pitt County and in 1961 became Assistant Superintendent to Donald Conley. In 1965, Alford was named Superintendent of Pitt County Schools.

At the start of Alford’s term as superintendent, Pitt County Schools operated under a Federal Court ordered freedom of choice plan for pupil placement. Then in May of 1968, the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that freedom of choice was an unacceptable plan which failed to integrate the schools and amounted to a dual system still divided by race. This led to a federal court order that provided specific details for the operation of Pitt County Schools that aimed to create a unitary school system. The court ordered “a 1/3 integration of Pitt County Schools” for the 1968-1969 school year which was to bring about total racial integration during the 1971 school year.

Alford was optimistic and committed to the integration of Pitt County Schools in the 1968-1969 school year. He and his leadership embraced the challenge; Alford realized that he, his teachers, and his students would have to contend with racial attitudes that were deeply rooted in the history of Pitt County, but was careful to acknowledge that “attitudes, customs, mores, [and] standards … which have been developed over the past 100 years are not going to be overcome in one, two, [or] three ... years.”

Alford took actions to engage the community and build relationships outside of the school walls. For instance, when two police officers in Pitt County’s small town of Farmville resigned, Alford encouraged the mayor to make a concerted effort to hire and retain African American police officers. Hiring more African American police officers would, according to Alford, demonstrate a preparedness to recognize the issues facing all community members.

In an attempt to soothe racial tensions, Alford stipulated that his principals should foster community understanding of the desegregation process with community meetings that increased collaboration with African American citizens. Alford also appealed to local African American leaders including D.D. Garrett -- the local NAACP leader of Pitt County -- and Dr. Andrew A. Best -- a local physician and civil rights leader whose influential voice commanded attention in Pitt County. Alford believed that because of Dr. Best’s work, Pitt County had less “disruption, moral decay and bitterness among the masses” resulting from Best’s encouragement of “greater thinking and greater loyalty” in school-aged children.

Alford understood that his efforts were only part of a long-term strategy to reinforce public schools. He stated in March 1971 that Pitt County had devised a plan he believed, for the first time, would mitigate the consequences of segregation and inequitable educational practices. He believed that this was the purpose of Title I funding, and that Pitt County Schools were reliant upon this and other federal funding to meet the educational needs of its children. So, when President Richard Nixon moved to diminish federal educational funding, Alford gave thanks to those elected representatives who overrode the President’s veto of the Education Bill, suggesting that local citizens were disinterested in “spending their funds for the public schools…[and that] unless we have continued assistance from the Federal Government, public education is lost and so is this country.”

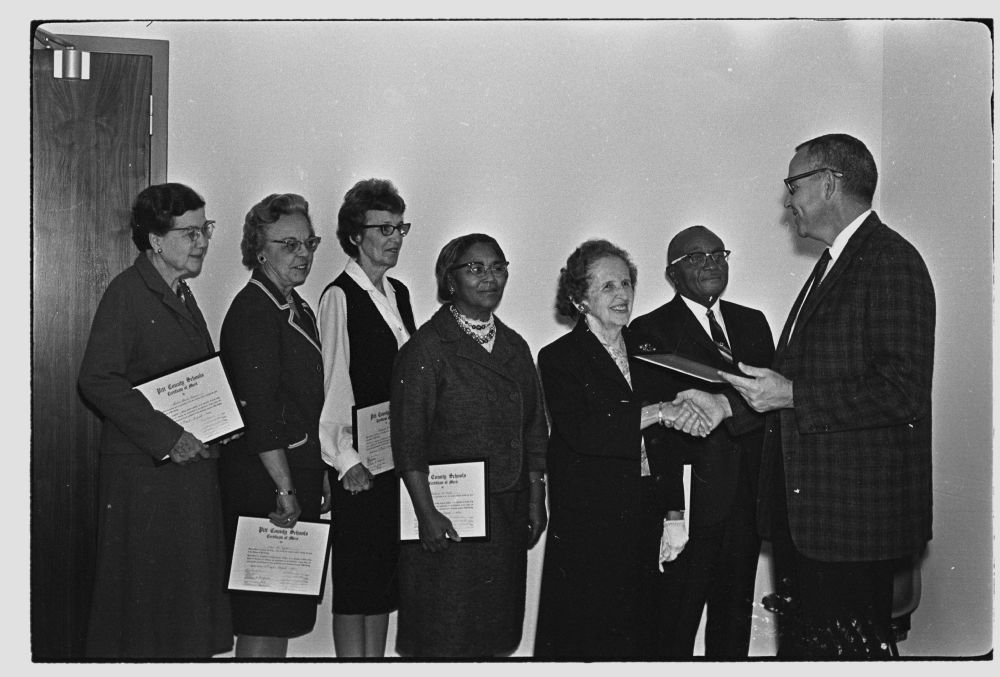

Alford was the recipient of many awards, recognitions, and positions of leadership that spoke to his leadership abilities and dedication as a public servant. Awards and positions earned include: the Distinguished Service Award from the American Association of School Librarians in 1980, State President of NCAE’s division of supervisors and directors, State President of the North Carolina High School Athletic Association, Chairman of the Blood Committee for the Pitt County Chapter of the Red Cross, Board of Directors for the Pitt County Society for Crippled Children, and Board of Directors for the Pitt County Mental Health Association.

Alford retired at the age of 52 in 1982 and soon after passed away on April 23. He was buried at the Pinewood Cemetery. He was survived by his sons -- Gary, Scott, and Randy -- and wife Betty J. “Bet” Alford.