Published with permission. For personal educational use and not for further distribution.

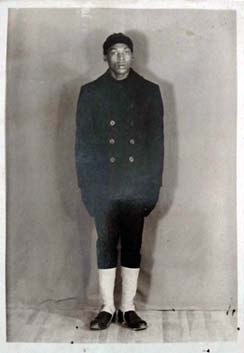

6 May 1915 - 28 May 2011

Denison Dover Garrett, an African American civil rights pioneer and businessmen, was born May 6, 1915, and he died on May 28, 2011 at age 96. D.D. Garret’s life served as a mirror to much of Pitt County’s history. Throughout his life, Garrett was an instrument of peaceful change. His 2011 obituary in the Greenville Reflector noted that he fought discrimination “intensely but with statesman-like style.”

Early life and education

Garrett was raised in the Belvoir Community. The family attended church at Fleming Chapel where his father was Superintendent of Sunday Schools. The church was used on Sundays for services but served as a school during the week.

D.D. Garrett’s father and mother farmed; the farm produced sweet potatoes, cattle, corn, hogs, and tobacco. When Garrett was a child, the size of a farm was defined by horse power. His family’s farm was ten acres, or a two horse farm. During the Great Depression the family lost the farm, and the experience left an indelible impression on D.D. Garrett. He recalled when collectors visited the house to collect anything of worth, including the family’s remaining food, hogs and collards. There was no due process back then, Garret said: “Repossession process in those days and times… was not a matter of if you were right or wrong, it was a matter of if you were black or white, that was the process of the law. If a white man said it, it was meant. If a black said it, you did not have to accept it.” It was after the family lost the farm that the family moved to Greenville, and Garrett dropped out of school.

During D.D. Garret’s “drop out period,” he worked at East Carolina Teacher's College as a grounds keeper. There he met a white co-worker student who told him that he was not getting paid, but working his way through college. Garrett decided to follow this example to solve his inability to pay tuition. He returned to his studies, graduated from high school and then entered North Carolina Central University, then called the North Carolina College for Negroes. It was in his junior year when he enlisted in the U.S. Navy during World War II.

Following a stint in the Navy, he earned a BA in Commerce from North Carolina College for Negroes. Following college, he moved to Greenville, North Carolina, where he was a successful businessman and entrepreneur from 1946 to 2011.

Civil Rights

Starting in the 1940s, Denison Garrett was at the forefront of breaking down Jim Crow Era color barriers. In 1944, he was the first black candidate for the Board of Aldermen, and in 1988 he was elected Greenville’s first African American County Commissioner. While he lived in Greenville, Garrett led the Pitt County chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) for almost twenty years. He was Greenville's first black Realtor, black public accountant, and opened the first black-owned insurance agency. In 2011, the leader of the NAACP Calvin Henderson said that Garrett was “the first Realtor to sell a black family a home in a white neighborhood.”

In 1948, President Harry Truman ended racial segregation in the United States military. Many historians argue that this marked the beginning of the modern civil rights movement. Before this, during World War II, Garrett was ahead of the President in taking action to combat racism in the Navy. Part of Garrett’s time in the Navy was spent in Washington State. He recalled: “It was in Bremerton, that I believe I encountered as much, or more, discrimination being segregated in Bremerton as I had any where . . . even here in Pitt County.” Garrett said, for example, in Bremerton, Washington, on the Ammunition Depot, “if we went to a movie theater, the black boys had benches with no backs to sit on, the white boys had chairs just across the aisle with cushions and backs we had benches with no backs.” And, if we were granted a leave, the bus would go to the white sailor to pick them up, while “we black boys would have to walk at least half a mile to get to the bus “and when we got to the bus,” Garrett said, “if our shoes were dirty . . . we were not allowed to get on the bus until we had clean shoes. So, we had to learn to carry towels to clean our shoes.” “When we got to Bremerton, Washington, and we had to walk down the main street and “the white folks had never seen this many colored men together . . . we created quite an excitement, folks came out of their business just to see us.”

Garrett served onboard the U.S.S. Charlotte, a supply ship that carried war materials from San Francisco to the Middle East. It sailed from San Francisco to the Middle East. When he first arrived on the ship, he was forbidden to go into the dining hall: “I was told by the cook that I could not come into that dining hall. So, I was escorted to my quarters onboard the ship. For three days, I stayed about that ship. I did not eat a “legal” meal. But other sailors snuck in small bits of food for him to survive. At the end of the third day of protest, Garrett could claim a small victory because soon, the Captain of the ship “announced that from henceforth, ALL sailors will eat in the dining hall.” While recognizing the need to combat the culture of racism in the Navy, Garrett understood the personal cost when he recalled that “I was never able to get promoted.”

While in the Navy, Garrett and twenty four other black servicemen also organized a “No Talk Campaign” as a non-violent form of protest about poor food and living conditions for black sailors. “If one sailor wanted a cigarette from another sailor, he would not ask for it aloud. He would walk over and whisper it in his ear. If a request was made from one sailor to another, it was in a whisper.” Garrett admitted that his group of black sailors were noted for their “loud, laughter and talking.” The silent whispers were designed to unnerve their superiors and draw attention to their complaints. Additionally, Garret and his fellow sailors also conducted a fast, or hunger strike of sorts: “We would eat only enough to survive. And made it a point that nobody ate all that they were given.” Garrett noted that “the base authorities got concerned. They called us in to question us about our behavior.” Noting that all the superior officers were white, Garrett and his crew had previously agreed that nobody would claim leadership for leading the protest against unequal treatment. If the question arose, “who did it?” Garrett said that the sailors’ response was that “we did it.” Finally, Garrett and his crew were asked what they “wanted and what would it take to end the fast.” The black sailors request was simple: “Treat us like you treat the white folk.” The black sailors ended protests when officers in his command agreed to their requests.

Garrett’s leadership for improved race relations did not end with his military service. In 1946, he was chosen to lead the local chapter of the NAACP. It was during Garrett’s administration that the stores in downtown were integrated: “We had conferences with the power structure, managers of hotels, managers of drug stores.” Garrett recalled that “It took place quietly” and that other places went through riots. “That was not the situation in Greenville,” he recalled. Nevertheless, obstacles remained for getting black voters to the polls to vote. The only organized demonstration by local African Americans, until 1963, was the “Christmas Sacrifice.” It involved a blackout of Christmas tree lights as a form of silent protest to racial prejudice. Only six African American houses in Greenville reportedly burned Christmas tree lights during the holidays that year.

D.D. Garrett was able to work within the black community with other black leaders. For example, Garrett had started his own school of bookkeeping and typing because there was demand in the black community for these job skills not being met by the school system. The Principal of the Colored Schools in Greenville, W.H. Davenport, asked D.D. Garrett if he would be interested in allowing the school system assume teaching of typing and bookkeeping, if he agreed to close his training school down. Both agreed to the proposition to advance the betterment of their mutual community.

Michael W. Garrett, D.D. Garrett's Son

Michael Garrett was D.D. Garrett’s son, and he played a part in the civil rights struggle in Greenville during the 1960s. He was one of the earliest to attend both the colored high school and the white high school. The first significant instance happened around 1960, when young Michael Garrett was instructed by his father to distribute “Get Out and Vote” flyers to students. While Michael had been careful to do this across the street from the black high school, C.M. Eppes, he was nevertheless chastised by the school’s principal, W.H. Davenport. According to Michael Garrett,“the concept of “voting was strictly prohibited at Eppes High School. The only time I was reprimanded at Eppes was for handing out “Get Out and Vote” fliers across the street from Eppes. I was given a tongue-lashing like you wouldn’t believe. I was given the Uncle Tom speech by my black principal, Mr. Davenport. It was the white supremacist doctrine from a black man’s point of view.” Garrett was told in no uncertain terms that he was not to hand out leaflets to students about getting blacks to vote: “You don’t want to go out upsetting those white folks. . . they give us our jobs. What do you think you are doing?” The principal told him: “don’t be agitating blacks to go out and vote.”

Plans to racially desegregate schools were controversial among both black and white residents in Greenville. In the 1964-1965 school year, Greenville started the process when Michael Garrett and one other black student were selected to break the color barrier at the all-white Junius Harris Rose High School. The 1964 entry of two black students into the all-white school amounted to token desegregation that was uneventful and peaceful; however, full desegregation in 1969-1970 was not peaceful. “When two of us were coming in ’64, there were great pains taken to insure that there wouldn’t be any problems. But when full scale integration happened in ’69, that was a different situation.” In 1969, there was “tremendous resentment.” The most prominent resentment, he asserted, was from the white community, but many blacks were too. They were being forced “out of their comfort zone.”

Garrett was in college by 1969. When he read the newspapers and saw that black students at J.H. Rose High School were rioting, he was “shocked.” Garrett said that it was “strange to me that Eppes’ students would go to a foreign environment and have enough confidence to fight and riot. Eppes was a very repressive environment. That was not part of the mentality [at Eppes].” The violence of 1969, “had to be provoked. I could not even get them to accept come out to vote flyers when I was there. And all of the sudden, they were rioting? Eppes kids were “not that politically astute.” “The difference between my experience in 1964 and what happened in 1969 was that “there were people on the black side and the white side who did not want things to go smoothly” in 1969.

Recollections of the Jim Crow Era

D.D. Garrett recounted the many smaller intimidations designed to remind blacks “to know their place” during the Jim Crow era. A person got along well, though, if they knew the rules and tried to abide by “the rules.” The rules included that blacks and whites mixing were off limits, “you just didn’t do it.” Disobeying the rules got people into trouble, said Garrett. There was a culture that said from what race to the other, “whatever it takes to keep these folks in a subordinate mind, we going to do that.” An example Garrett cited was about when his oldest sister who had picked cotton and at the end of the day she weighed the cotton and figured out how much the man owed her. When she told the man how much he owed her, he fired her. He did not want anybody on that farm who was able to figure their own wages. This was a way of keeping people in a submissive form. Another way of keeping blacks submissive was stores, where, for example, black men and women were not allowed to try on hats. If a black individual tried a hat on, he or she had to buy it. Register of deeds offices listed property owned by citizens in separate books.

Jim Crow racial etiquette dictated black teachers’ interactions with the community. He highlighted the example of Charles Montgomery Eppes, the supervising principal of Greenville’s Colored Schools from 1903-1942: “Eppes had a philosophy, for example, that if a black teacher who taught at Eppes School had an automobile . . .” they should park it elsewhere and not drive that car into downtown Greenville. “You walk uptown. Don’t let the white folks know or think that you are doing too well.”

Later years

During Black History Month in 2006, Garrett gave an interview where he encouraged “the black community to be more involved in what he called the three B's - books, bucks and the ballot.” Books were necessary because they were needed to be more literate in all areas; Bucks were needed to help people become more independent; and the ballot was, of course, the need to go out and vote.

When he was 90 years old, Garrett was awarded the honorary lifetime membership to the national honor society by the East Carolina University chapter of Phi Kappa Phi. Garrett was a recognized leader in the AME Zion Church and the N.A.A.C.P. , Pitt County Substance Abuse Coalition, the Greenville Bicentennial Commission, and the Pitt County Democratic Party. He received numerous awards, including the Pitt-Greenville Chamber of Commerce Citizen of the Year, Omega Psi Phi Citizen of the Year, Pitt County Black Civic Group Life Achievement Award, ECU Department of Sociology Community Service Award, and the Pitt Infant Mortality Advisory Council Outstanding Service Award.”

In 2011, Calvin Henderson, Greenville’s head of the NAACP noted that "It took a lot of courage," for D.D. Garrett to run for political office, and agitate for change in the race based status quo: "He was one who was not afraid to step out and challenge the laws of the Jim Crow era. He was willing to say he wanted to begin the fight for change."

Garret’s son, Michael, was witness to his father’s efforts and recalled that "Getting people to vote was a struggle," because Jim Crow laws were in full force and even middle-class, professional blacks were afraid to vote. "Daddy struggled for years to establish voter registration in the black community," Michael remembered. D.D. Garrett ran for political office multiple times and met defeat often. But he did not quit. His first run for election to the Board of Alderman netted him only 44 votes. He made several unsuccessful runs for Greenville city council before two other African Americans were more successful: Reverends John Taylor and Clarence Gray were the first African Americans elected to city office in 1974.

Nevertheless, Garrett served as a guide post and inspired others to be more engaged in their life.

"D.D. Garrett is the reason why I became a county commissioner, "asserted Pitt County Commissioner Melvin McLawhorn. "I watched him through the years and he inspired me to become a commissioner because of his concern for the community."

"He was a pioneer in the area of Civil Rights and minority business. Things that people take for granted, voting, employment in the retail industry: these were hard fought battles that he led," Michael Garrett said that his father’s advocacy for racial equality was far reaching.

When he passed away on May 28, 2011, D.D. Garrett was survived by his wife of sixty-nine years, Clotea, and their two sons Michael and Denison D. Garrett Jr.

Following Garrett's death, North Carolina Congressional Representative G.K. Butterfield made an address to the U.S. House of Representatives paying tribute to D.D. Garrett: "D.D. Garrett was a man of great courage who led by example. He worked tirelessly to ensure that the African American community had a voice in public policy. Through his work in the AME Zion Church and the Pitt County Branch of the NAACP,D.D. constantly exposed injustice. He insisted that the American Dream must be a reality to every American regardless of their station in life."