WWI: Medicine on the battlefield

From a medical standpoint, World War I was a miserable and bloody affair. In less than a year the American armed forces suffered more than 318,000 casualties, of which 120,000 were deaths. Almost 6,000 of these casualties were North Carolinians.

When the United States entered the war in 1917, the army did not have an established medical corps. During the war, the army medical corps copied parts of the French and English medical system that had been in use for the past three years. This system arranged military medical staff in a practical manner. Stretcher-bearers first came into contact with the wounded and moved them from trenches to waiting ambulances. The first aid treatment these medics gave often saved lives. Lieutenant Andrew Green wrote to friends in Raleigh praising the stretcher-bearers who carried him over one mile through enemy shell fire after he was wounded in the leg. Private Clarence C. Moore related that he “was a stretcher bearer in the Hindenburg Line for about half a day. We had to step on these dead soldiers to keep from going in the water and mud so deep and throwing the [wounded] off the stretcher. . . . “

Motorized transport proved to be the fastest and most efficient way to move the wounded. Ambulances rushed them to mobile dressing stations or field hospitals that followed the advancing and retreating troops. From there the severely injured were taken to base hospitals far behind the lines. North Carolinians organized and staffed the 317th Ambulance Company and Base Hospital 65.

Felix Brockman of Greensboro volunteered for the 321st Ambulance Company, which was made up of men from the Greensboro and Winston-Salem areas. He recorded that wounded men were brought from the battlefield to a triage area to be sorted out. Generally there were four kinds of cases: gas injuries, shell shock, diseases, and wounds.

World War I was the first conflict to see the use of deadly gases as a weapon. Gas burned skin and irritated noses, throats, and lungs. It could cause death or paralysis within minutes, killing by asphyxiation. As soon as troops learned that gas was in their area, they had to put on masks. Even having the fumes in their clothing could cause blisters, sores, and other health problems. Bathing and changing clothes immediately helped but was not always possible. Many thousands of gas victims suffered the painful effects of damaged lungs throughout their lives. The use of these gases was banned after the end of World War I.

Some injuries were not physical. Most soldiers got used to living in muddy areas filled with rats, rotting corpses, and exploding shells, but others could not. As the war progressed, a mental illness caused by these conditions became known as shell shock. Sufferers could be hysterical, disoriented, paralyzed, and unable to obey orders.

Soldiers lived and fought in trenches that were little more than swamplike holes in the ground—a perfect breeding ground for disease. Doctors and nurses could do little to help soldiers with influenza and intestinal flu, and these diseases killed more men than machine gun bullets.

Unmerciful pests such as lice also lived in the trenches. One North Carolinian remarked, “At first we had only one kind [of lice]; but now we have the gray-back, the red, the black, and almost every color imaginable.” Lice lived on the soldiers' unclean clothes and bodies. The only way to get rid of the itchy pests was to bathe and change clothes, but often weeks passed before they could do this. Many soldiers also suffered from what doctors called trench foot. After they stood in water for weeks at a time, their socks would begin to grow to their feet. In severe cases, the soldiers’ feet had to be amputated.

Women as well as men cared for the injured and ill. Thousands of women volunteered as nurses, and many worked at least a fourteen-hour day in the hospitals. They often had to come back on duty when hospital trains arrived with more wounded soldiers. Nurses also served in evacuation hospitals only eight or ten miles behind the front lines and well within the range of German artillery. Wounded soldiers remarked that having female nurses as part of the medical staff was very important. Their skillful care saved many lives, and they reminded the injured of their mothers, wives, girlfriends, and sisters back home.

Military medicine had not changed much in the fifty years since the American Civil War. Battlefield doctors were slow to understand the link between exposure and the infections that set in quickly in dirty battlefield hospitals. As doctors became more aware of this link, they had to make sure that the wounded were brought to the operating table within twelve hours or the risk of infection greatly increased. There was only salt water to rinse wounds, and there was no medication to stop infection once it had started. Thousands of men lost arms, legs, and even their lives.

But advances in some medical techniques kept pace with the mass destruction of war. Doctors developed and practiced new ways to treat severe cases of tissue damage, burns, and contagious diseases. Blood transfusions were given under battlefield conditions. Doctors began using X-ray equipment to locate bullets and shrapnel during operations. The quality of American base hospitals increased as their medical staffs grew used to the rigors of the western front.

Even though medical staffs improved over time, the average soldier did not trust doctors. Marion Andrews of Winston-Salem got a piece of shrapnel in his leg when a wagon he was sleeping in was hit by a German shell. He refused to report to a field hospital, hoping that the wound was minor. After a week he found he had developed blood poisoning, and only then did he surrender to the treatment of doctors.

When it became absolutely necessary, the United States developed a medical corps. At first its training and equipment was wholly lacking and it was ill-prepared to deal with war. But as Americans began to enter combat, the corps produced a workable medical system and actually made advances in the field of medicine.

At the time of this article’s publication, John Campbell served as field registrar in the Collections Management Branch of the North Carolina Museum of History.

Additional resources:

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

"Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI." State Archives of North Carolina. N.C. Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm (accessed September 25, 2013).

"World War I." North Carolina Digital History. Learn NC. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newcentury/3.0

WWI: NC Digital Collections. NC Department of Cultural Resources.

"WWI: The Old North State and 'Kaiser Bill.'" State Archives of North Carolina.N.C. Department of Cultural Resources. 2005. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/OldNorthState/index.htm (accessed September 25, 2013).

BBC. How did World War I change the way we treat injuries today? http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zs3wpv4 (accessed January 20, 2017).

Birtish Library. Wounding in World War I. https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/wounding-in-world-war-one (accessed January 20, 2017).

Sciencemuseum.org. Medicine in the War Zone. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/themes/war/warzone (accessed January 20, 2017).

Battlefield medicine: search results from WorldCat. https://goo.gl/I0i2rO (accessed January 20, 2017).

Manring, M. M. et al. "Treatment of War Wounds: A Historical Review." Clin Ortho Relat Res. 2009 Aug 467(8). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2706344/ (accesed January 9, 2017).

Image credit:

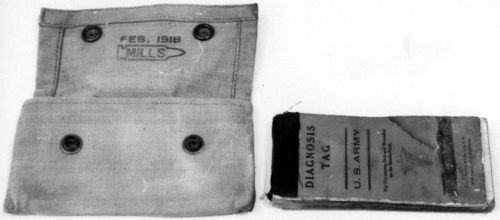

"Diagnosis tag book." 1917-18. Made by William J. Brewer. NC Museum of History. Accession No. H.1961.63.124. Online at http://collections.ncdcr.gov.

1 May 1993 | Campbell, John