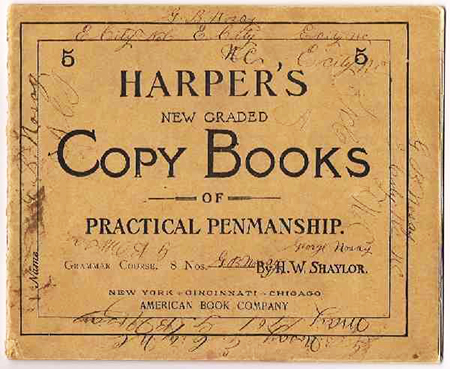

Penmanship as a deliberate manner of writing was scarcely practiced in North Carolina until the nineteenth century and, with the rise of computers by the end of the twentieth century, was in danger of becoming an educational relic. The rise of private academies in the state early in the nineteenth century coincided with the availability of copybooks that were designed and published by acknowledged writing masters in the North. Copybooks contained engraved specimens of capital and small letters and were published as aids to the teaching of a variety of hands. Most popular was the current (or running) hand in which the letters were usually slanted to the right and the words formed without lifting the pen from letter to letter. In round (or copperplate) hand, the slope also inclined to the right, but the letters were round, bold, and full.

In most North Carolina academies, boys and girls were given the same kinds of primary copybooks in which to copy short letters, short and long letters combined, and short words commencing with capitals. While girls were expected to master the techniques to a degree higher than boys, both might have examples of their penmanship separately scrutinized in a public examination at the close of the school year.

Two men from the world of classical writing masters dominated penmanship in the state's public schools during the first half of the twentieth century. Charles Paxton Zaner (1864-1918) of Ohio and Austin Norman Palmer (1860-1927) of Iowa both had been influenced by Spencerian forms, but both, in their specimen alphabets for schools, abandoned elongated loops, flourishes, and shading of letters. Palmer's method of moving particular muscles in writing while resting the fleshy part of the forearm on the desk was of advantage to commercial writers. Beginning in 1916, texts and writing books of the Zaner-Boser Company and the Palmer Company were used exclusively in the primary and commercial writing classes in the state's public schools.

With an ever-increasing reliance on home computers for homework and other assignments, penmanship has become systematically de-emphasized in North Carolina school systems. By the early 2000s, schools often required assignments to be typed rather than handwritten, and many students simply have never been made to learn the basics of modern cursive techniques, such as the D'Nealian method. With keyboards replacing pens and pencils, the future of penmanship in the state remains unclear.