1835 Constitutional Convention

Originally published as "It Needed to Change before the State Could Grow: The Constitutional Convention of 1835"

by Thomas E. Jeffrey

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 1996; Revised October 2022.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: State Constitution; Black and Tan Constitution; Convention of 1835 (from Encyclopedia of North Carolina); Convention of 1868; Convention of 1875; Governor.

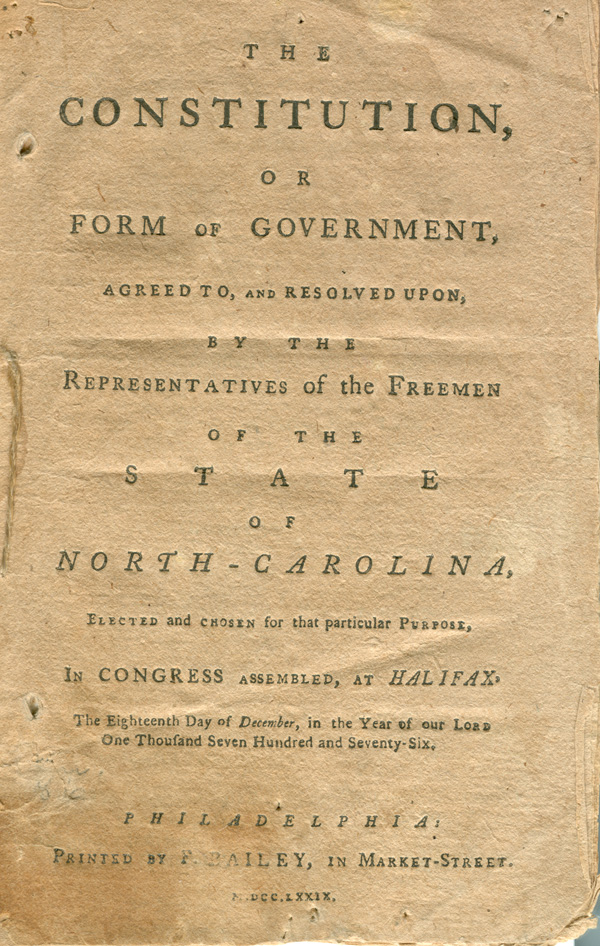

Reforming the state’s constitution was one of the most important and hotly debated political issues in antebellum North Carolina. The state’s constitution of 1776, which remained largely unchanged until the convention of 1835, had features that many North Carolinians had come to regard as unfair and undemocratic. The most widely criticized section related to the method of apportioning seats in the General Assembly.

Reforming the state’s constitution was one of the most important and hotly debated political issues in antebellum North Carolina. The state’s constitution of 1776, which remained largely unchanged until the convention of 1835, had features that many North Carolinians had come to regard as unfair and undemocratic. The most widely criticized section related to the method of apportioning seats in the General Assembly.

Before 1835, each county was allowed to elect two members to the lower house, known as the house of commons, and one member to the state senate. Since most of the state’s counties were located in the eastern part of the state, the east had more representatives, which enabled it to maintain control of both houses of the General Assembly. But by the antebellum period, the western counties had grown to cover a larger area and were growing faster in population. In fact, by 1830, most North Carolinians lived in the west, and the 1776 system of apportioning representation seemed to them an obvious violation of the democratic principle of majority rule. In addition, the eastern-controlled legislature repeatedly defeated efforts by westerners to construct roads and other transportation improvements in the west. Western citizens believed that economic development of their section would not be achieved until the state’s constitution was amended to give them a fair share of seats in the General Assembly.

Other Problems with the Constitution of 1776

North Carolinians from both sections of the state were united in their dissatisfaction with other parts of the 1776 constitution. Residents of rural counties resented the fact that seven towns (the “boroughs” of Edenton, Halifax, Hillsborough, New Bern, Wilmington, Salisbury, and Fayetteville) had the privilege of electing additional members to the house of commons. Another objectionable feature was Article 32, which prohibited Catholics, Jews, and members of other faiths who denied the “being of God or the truth of the Protestant religion” from holding office.

The 1776 constitution contained numerous parts that many considered undemocratic. For example, justices on the county courts—who served as the principal officers of local government in North Carolina—were appointed for indefinite terms by the General Assembly rather than being elected periodically by local voters. Likewise, the governor, state judges (such as those on the supreme court), and most other state officials were appointed by the legislature, not by popular vote. Elections for state senators were open to voters, but those voters had to meet certain qualifications, such as owning at least fifty acres of land.

Ironically, the 1776 constitution made no mention of race as a qualification for voting. As a result, free blacks could and did vote in state elections. That practice displeased many white voters—particularly in the heavily-enslaving east—who wanted to restrict voting to whites.

Still, the vast majority of easterners were willing to tolerate these displeasing aspects of the 1776 constitution because they did not want to risk changing the balance of power in favor of the west. On numerous occasions the eastern majority in the General Assembly defeated convention bills that had been introduced by western politicians. By the 1830s, though, frustrated reformers were threatening to call a convention without the General Assembly’s approval (they could have done that by encouraging local sheriffs, who were in charge of coordinating elections in antebellum North Carolina, to organize an election). Reformers also threatened to secede from North Carolina and set up their own state. Such threats of revolutionary action led a few prominent easterners like William H. Haywood Jr. to join the reform movement in the hope of moderating and controlling it.

Finally, the East Wants Reforms, Too

By the early 1830s, other factors were beginning to influence some easterners to adopt a more sympathetic attitude toward constitutional reform.

One important influence was the introduction of rail transportation. Leaders in eastern towns like New Bern and Wilmington suddenly began to see that internal improvements could transform their sleepy towns into thriving commercial centers. They began to view western reformers, who also supported transportation improvements, as allies in a crusade for state-financed railroads rather than as sectional enemies. In 1834, about twenty reform-minded easterners managed to win election to the General Assembly. In addition, Governor David L. Swain, whose popularity extended beyond his native west, threw his influence behind reform and presented the new legislature with a compelling argument for holding a convention. A reluctant reformer, Haywood was put in charge of drawing up the bill that would authorize a convention.

Haywood’s bill called for a special election to be held in April 1835. At the election, voters would be asked to approve a convention and to elect delegates to that convention. In order to win the needed support of Haywood’s fellow easterners, the bill placed severe limitations on the convention’s results. It ensured that easterners could control the convention by providing that two delegates would be elected from each county. And instead of giving convention delegates the power to write an entirely new constitution, the convention bill limited their activities to considering specific amendments to the existing 1776 constitution.

Haywood’s bill called for a special election to be held in April 1835. At the election, voters would be asked to approve a convention and to elect delegates to that convention. In order to win the needed support of Haywood’s fellow easterners, the bill placed severe limitations on the convention’s results. It ensured that easterners could control the convention by providing that two delegates would be elected from each county. And instead of giving convention delegates the power to write an entirely new constitution, the convention bill limited their activities to considering specific amendments to the existing 1776 constitution.

Haywood’s bill provided that delegates to the convention would create a new house of commons that would contain between ninety and 120 members apportioned according to “federal population” (defined as free population plus three-fifths of the population of enslaved people—the same system used for apportioning the U.S. House of Representatives). North Carolina’s more populous west would gain a majority of seats to control this lower house. The bill also instructed delegates to create a new senate that would contain between thirty-four and fifty members apportioned according to the amount of taxes paid by their districts into the state treasury. That arrangement enabled the wealthier east to keep more seats and its majority of control in the senate. Representatives to the new house and senate would be elected in August 1836.

On December 31, 1834, Haywood’s bill passed the house of commons by a four-vote margin. Despite the numerous restrictions and safeguards he had placed in the measure, only a few fellow easterners supported it. Three days later, the senate approved the bill by one vote. As expected, western legislators overwhelmingly supported the bill. Most of the easterners who finally supported the convention bill were associated with the railroad movement.

The special election that was held in April 1835 to select delegates approved the convention by a vote of 27,550 to 21,694. The vast majority of favorable votes came from the west.

The Convention Meets for Change

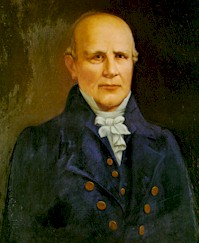

The convention, which assembled in Raleigh on June 4, 1835, consisted of 130 delegates representing thirty-eight eastern counties and twenty-seven western counties. Veteran politician Nathaniel Macon was unanimously chosen as its president.

The first amendment to win approval was elimination of borough representation. Most support for that proposal came from eastern delegates who represented small rural counties that resented the privileges boroughs had held. They also wanted to punish borough representatives for supporting the convention bill.

Eastern delegates were also responsible for defeating a proposed amendment to abolish religious restrictions on officeholding. The delegates did, however, agree to change Article 32 by allowing all “Christians,” rather than just “Protestants,” to hold office. Easterners again provided most of the votes for an amendment to prohibit free blacks from voting.

As directed, the convention made some significant changes in the structure of state government. The number of legislators was set at 120 for the house of commons and fifty for the senate—the maximums allowed by Haywood’s convention bill. Other amendments transferred election of the governor from the General Assembly to voters, extended the governor’s term from one to two years, and provided that the General Assembly would meet biennially (once every two years), instead of annually (every year) as before.

After approving the entire package of amendments with only twenty negative votes, the convention adjourned on July 11, 1835. As required by the convention bill, the new amendments were submitted to voters to be ratified. About 90 percent of the votes in favor of the proposed changes were cast by westerners. A similar percentage of the votes against them were cast by easterners.

The Most Noted Results

Constitutional changes approved in 1835 had an important impact on the citizens of North Carolina. The changes played a major role in reducing east-west sectionalism, because they gave the west more power in the General Assembly. Legislation favorable to the growth of the backcountry and Mountain region, such as creating new counties and providing state aid for internal improvements, could now be enacted more easily.

Constitutional changes also had a significant influence on parties and politics. Now that governors had to fight for popular votes statewide, campaigns had to be coordinated. These biennial governors’ campaigns provided the citizens of North Carolina with a statewide forum for discussing important political issues and hastened the development of a two-party political system.

In spite of the benefits most white North Carolinians received as a result of constitutional reforms, North Carolina’s government remained one of the least democratic in the South. For example, North Carolina continued to be one of the few southern states to require voters and officeholders, like candidates for governor and members of the General Assembly, to own property before they could vote or run for office. And since representation in the state senate was based on property ownership and wealth rather than population, enslaving counties continued to have a disproportionate influence over legislation. Moreover, constitutional reform was actually a step backward for free African American North Carolinians: They lost the right to vote altogether.

*At the time this article was written, Thomas E. Jeffrey was the associate director of the Thomas A. Edison Papers, a project sponsored by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and the National Park Service.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: North Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1835. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/NCConstitutionalConvention1835...

Additional Resources:

LearnNC, 1835 Amendments to the NC Constitution: http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newnation/4528.

North Carolina General Assembly, North Carolina Constitution: https://www.ncleg.net/Legislation/constitution/ncconstitution.html.

Image Credits:

The Constitution, or Form of Government, Agreed to, and Resolved Upon, by the Representatives of the Freemen of the State of North Carolina. Philadelphia: Printed by F. Bailey, 1779. Title page. North Carolina Collection. Located at http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/nchistory/dec2005/thismonthimage1.html. Accessed on 3/2/2012.

LearnNC: Nathaniel Macon. Located at http://www.learnnc.org/lp/multimedia/11370. Accessed 3/2/2012.

North Carolina History Project, Constitution of 1835. http://www.northcarolinahistory.org/commentary/32/entry.

1 January 1996 | Jeffrey, Thomas E.