From "Collecting Nature: The Beginning of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences." Reprinted with permission.

The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences has inspired wonder for generations. Stories are still told about George, the fifteen-foot Burmese python that was a museum fixture and favorite for many years. The inspiration reached new heights when the museum’s new building opened in downtown Raleigh in April 2000. Four floors of exhibits included a twenty-foot waterfall cascading into a pond of living fish. A ferocious, predatory dinosaur that once roamed what is now the Southeastern United States patrolled a glass dome overlooking Jones Street. Around every corner, visitors could get an in-depth view of the unique natural history of the state, and the amazing diversity of plants and animals that call it home.

When the museum opened its doors in 1879, visitors saw a much different mixture of exhibits. Agricultural products—from tobacco to cotton to silk—represented farm life in most of North Carolina’s counties. Twelve-inch spheres of polished granite, marble, and leopardite promoted the state’s famed building stone. Porcelain plates and building bricks made from Piedmont clays were shown, along with gold, silver, and copper ores. Soon, two brothers from England would become the leaders of the museum and guide it down a different path.

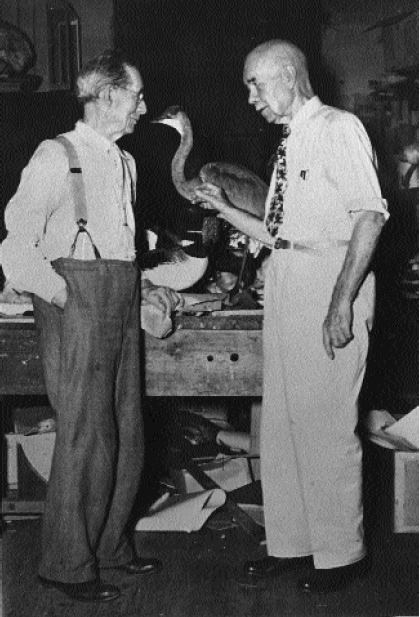

Herbert Hutchinson Brimley and Clement Samuel Brimley served North Carolina in North Carolina Office of Archives and separate capacities for nearly sixty years. One History. brother, H. H., was a hunter and naturalist who pioneered interpretive exhibitions and programs at the museum. The other Brimley, C. S., was a scientist and collector who carefully built the animal-related collections that formed the basis of his brother’s work.

The Brimleys grew up in the collecting tradition of middle-class England, but times there were tough. A chance meeting with an eager recruiter from the North Carolina Department of Agriculture’s Division of Immigration and Statistics convinced them that the state held great promise for hardworking people like themselves. After arriving in Raleigh in 1880, the brothers found new frontiers and possibilities for their natural history investigations, trying their hands at “collecting bird skins and eggs for wealthy men in the big cities.” They soon were publishing papers in birding journals.

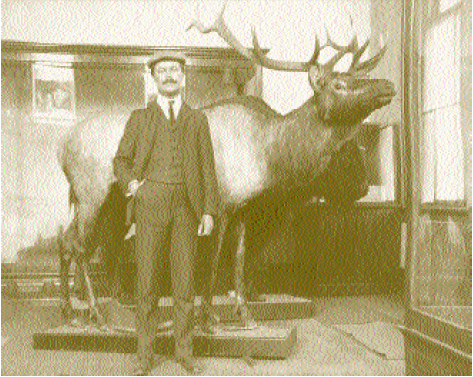

The Department of Agriculture contracted the older brother, H. H., to create displays of game fishes and waterfowl that would interest the state’s sportsmen. A robust outdoorsman, H. H. played up the romance of the hunt in his exhibits, following a trend of natural history in the United States and in Europe. His displays won prizes, and in 1895 the department hired him as the first full-time curator of what then was the State Museum. Later, he became the museum’s first director.

Tension arose when the 1913 Board of Agriculture warned H. H. that his exhibits were wandering too far from a focus on farming. His passion was for natural history—especially the fishes, birds, reptiles, and whales. Nature study and conservation movements were gaining ground in the state, and H. H. felt justified in nudging exhibits and collections closer to pure natural sciences. He reminded board members of the 1879 statute requiring the State Museum to illustrate North Carolina’s natural history. Brimley also said, “A long and close study of our visitors proves very conclusively to me that a large majority prefer to observe and study objects on natural history above all other exhibits.”

Natural history won the battle. Over the next fifty years the museum’s exhibits reflected the interest in natural history shared by H. H. and the public, an interest often served by large, impressive specimens. In 1928 H. H. reported,

“The big bull sperm whale, fifty-five feet in length, is one outstanding specimen, both as to size and as to comparative rarity, that has ever come to the museum. There may also be mentioned the large ocean sunfish, from Swansboro, estimated to weigh between 1,200 and 1,300 pounds; an eleven-and-a-half-foot alligator; an octopus with a five-foot spread of arms; a sixteen-foot thresher shark from Wilmington; a very large red drum from Ocracoke; a large specimen of black bear; . . . a yellow raccoon, a pure albino opossum, and a number of specimens of rare birds.”

C. S. Brimley worked alongside his brother but collected for science, not for display. At the age of sixty-two, he modestly claimed that his “main interest for many years zoologically has been to gain and disseminate knowledge about the fauna of North Carolina, both vertebrates and invertebrates.” His legacy to the natural sciences includes more than two hundred animal-related papers, the landmark books Insects of North Carolina and Birds of North Carolina, and descriptions of new species of amphibians and insects. His detailed field records supported published surveys on the amphibians and reptiles of North Carolina, the mammals of the state, and a partial account of fishes of the state.

A self-taught scientist, C. S. started and indexed the zoological collections of the State Museum. His legendary concern for the state’s collections has been handed down from one curator to the next through four generations. Now, 127 years after its founding, the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences houses more than 1.7 million specimens in its collections—from birds and insects to frogs and fish to rocks and fossils.

The two Brimley brothers died within three months of each other in 1946, having shaped the state’s collections and public opinions through six decades of big changes. They arrived in North Carolina when gray wolves and panthers still roamed the woods, and they documented nature until the dawn of the atomic age. Each brother in his own way gave North Carolinians a broader understanding of the natural world, and each found in his adopted state and its museum a place to indulge his passion for nature.