Reprinted with permission from North Carolina Civil War Sesquicentennial

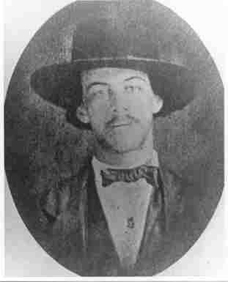

Lewis S. Leary

17 Mar. 1835-17 Oct. 1959

Note: This article discusses the lives of two free men of color from North Carolina, John A. Copeland and Lewis S. Leary, whose lives were linked by a family connection and who both participated in John Brown's raid at Harper's Ferry. A separate entry has been created in NCpedia for each man. This entry serves as a biographical entry for Lewis Leary. John Copeland's entry can be found here. Both entries contain the same text, with individualized biographical details at the top of the entry.

John Brown at Harper's Ferry: Background

On the evening of October 16, 1859, abolitionist leader John Brown and twenty-one compatriots launched a raid on the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). His party consisted of white and free black people, as well as formerly enslaved people and freedom-seeking enslaved people. In the group were two North Carolina natives, Lewis S. Leary of Fayetteville and John A. Copeland Jr. of Raleigh. Brown was fully convinced that once the U.S. arsenal had been taken, several hundred local enslaved people would join him. His objective was to arm them and take control of western Virginia, spreading an abolitionist rebellion throughout the South.

Brown, described by Abraham Lincoln as a “misguided fanatic,” had developed a reputation as a militant during the “Bleeding Kansas” crisis of the 1850s. Dissatisfied with the majority of abolitionists who advocated peaceful resistance to Southern enslavement, Brown demanded violence. In May 1856 he and several supporters murdered pro-slavery civilians along Pottawatomie Creek in Franklin County, Kansas, in what became known as the Pottawatomie Massacre. For the next several months, Brown and a growing band of supporters did battle on the Kansas-Missouri border with enslavers; Brown’s son was killed in a related skirmish.

From 1857 to1859, Brown traveled throughout the country espousing his beliefs, and challenging abolitionists to take a more active and violent stance. From his writings, it is apparent that by 1858 Brown was no longer focused on Kansas, but instead had formulated the idea of inciting an abolitionist rebellion in the mountains of Virginia. Precisely when the idea coalesced in his mind for an attack on Harpers Ferry is unclear, but Brown appeared in the town in early July 1859 under the alias Isaac Smith. He subsequently began stockpiling weapons at a nearby farm, and developed the plan of attack over the succeeding months.

During the night of October 16, his plan was put in motion: Brown and his men cut telegraph wires, captured the armory, and took hostages, including Lewis Washington, grandnephew of George Washington. The armed uprising did not transpire as Brown planned. The first person killed by Brown’s party was actually a railroad employee and freedman, Heyward Shepherd, who stumbled upon them in the twilight hours. Only a handful of local enslaved people joined Brown’s group. The following morning, he and his party were surrounded by local militia in several buildings in the town. Fighting escalated throughout the day, and a number of the raiders as well as civilians were killed and wounded. Several of the attackers managed to escape shortly before nightfall, convinced that the expedition had failed. Brown and his surviving men were left trapped inside a small engine house, later known as John Brown’s Fort.

Word of the attack spread quickly throughout Virginia, and by 3:30 PM, President James Buchanan had ordered a detachment of U.S. Marines to deploy to the town. He chose a cavalry officer who had been home on leave, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, to command them. Lee and the Marines arrived in the evening hours of October 17. The following day they stormed the engine house killing or capturing everyone inside.

John Brown Raid

On November 2, after a two-week trial in Charles Town, West Virginia, and forty-five minutes of deliberation by the jury, Brown was convicted of multiple murders, treason, and inciting a slave rebellion. A month later, he was hanged. Six of his surviving co-conspirators suffered the same fate after their own trials.

Tar Heels at Harper's Ferry: John A. Copeland and Lewis S. Leary

The two North Carolina natives among Brown’s men had remarkably similar backgrounds in addition to being related by marriage. Born a year apart, Lewis S. Leary and John A. Copeland, Jr. were free, mixed race, and the children of free people. They both came from educated, hard-working and well-respected families. One was a harnessmaker and leatherworker, the other a college student. One came to the north in his early twenties following in the path of several siblings; the other traveled there as a child with his family.

John A. Copeland Jr. was born in Raleigh on August 15, 1834, one of the eight children born to John Copeland Sr. and his wife Delilah Evans, both multiracial free people. John and Delilah had married in Raleigh in August 1831. Delilah had been born free, while John was manumitted in the will of his master. In 1843 the family moved north, first intending to move to Indiana, but finally settled in Oberlin, Ohio.

Oberlin was considered by many to be the most racially progressive town in America. Conceived as an integrated community, the town boasted Oberlin College, one of the first higher learning institutions to grant admission to black people. Oberlin became a major center for the abolitionist movement and an important hub on the Underground Railroad.

Lewis S. Leary, born in Fayetteville on March 17, 1835 was the son of Matthew N. Leary Sr. and his wife Julia A. Menriel Leary, both of whom were mixed-race. Leary’s ancestry on his father’s side can be traced to an Irish grandfather, Jeremiah O’Leary, who served in Nathanael Greene’s army during the American Revolution, and a free woman of mixed Native American and black heritage. His great-grandfather on his father’s side, Abram Revels, a free black man, was also a Revolutionary War veteran. Leary’s mother was the granddaughter of “French Mary,” a West Indian freed woman and well-known Fayetteville cook, whose culinary skills delighted the Marquis de Lafayette during his visit to the town in 1825.

The 1850 census shows the Leary family living in Fayetteville, where Matthew Sr. was a saddler and harnessmaker. Both Lewis and his older brother Matthew Jr. are listed as saddlers as well, having taken up their father’s occupation. An apparently well-respected free black craftsman, the census states that Matthew Leary owned three enslaved people in 1850: a 14-year-old female, as well as two males ages 30 and 45. Leary is not listed as owning any enslaved people by 1860, possibly indicating that he had purchased those individuals, perhaps members of his or his wife’s family, to free them.

In 1856, at age 21, Lewis Leary left Fayetteville for Oberlin where several of his sisters had moved previously and married. One sister, Sarah, had married Henry Evans, the brother of Delilah Evans Copeland, the mother of fellow John Brown party conspirator John A. Copeland Jr. Leary married a local black woman, Mary Patterson, in May 1858, with whom he fathered one daughter.

Precisely what led these two young men to become radicalized and join John Brown’s movement remains uncertain. Although Copeland was the son of a former enslaved person and Leary the grandson, neither had been forced to break the bonds of slavery themselves. Nevertheless, they had both spent their childhood in North Carolina surrounded by the institution in all its horror.

Copeland, the first to leave North Carolina, did so in 1843, followed by Leary thirteen years later. They did so in a period of economic upheaval for black people and white people alike. The two previous decades had been a period of severe economic strain in the east, owing in part to the economic crisis of 1837. Tens of thousands of Americans had begun moving west between 1830 and 1840, particularly into the Deep South states of Alabama and Mississippi. These individuals took the people they enslaved with them, and many more enslaved people were sold to people in the west to pay off debts. Copeland and Leary likely witnessed enslaved families torn apart, as owners sold them west, or moved wives away from husbands and parents away from children.

Life as a free black or mixed-race person in North Carolina varied considerably with location and occupation. In 1840, three years before Copeland’s family left Raleigh, Wake County had 7,996 enslaved people and 1,009 free persons of color. This ratio of one free person to every eight enslaved people was higher than the state ratio of one free person to eleven enslaved people. Ten years later, Lewis Leary and his family were among the 862 free persons of color living in Cumberland County. Enslavers in the county held 5,392 people in bondage, a ratio of one free person to every six enslaved people. These figures were not the norm for North Carolina, but rather represent a more urban environment than most counties.

Most free people were farmers or tenants, but the most economically fortunate were those with trades. Both Leary and Copeland’s fathers were artisans, one a harness and saddlemaker, the other a carpenter. Their fathers were also both property owners. However, life for free black people continually deteriorated between 1830 and 1850. In 1831, North Carolina enslavers were panicked by a slave rebellion led by Nat Turner in southern Virginia and an aborted similar revolt in Duplin and Sampson Counties. As a response, slave patrols became more common, and severe restrictions were placed on enslaved people and free people alike. In 1835, the new North Carolina state constitution forbade free black people and mixed-race people to vote, a right they had held for over a century and a half. By 1840, free black people were restricted from owning weapons of any type without a license. Free black people in Raleigh were forced to apply for a permit from the board of commissioners to live there.

The fathers of both young men were active anti-slavery advocates. John Copeland Sr. became heavily involved in the Underground Railroad during the 1850s. At the 1852 Ohio State Black Convention, Copeland was chosen by convention president John Mercer Langston as the chairman of the Lorain County fugitive slave assistance committee. Leary’s father was well known for purchasing and freeing enslaved people within Cumberland County. Matthew Leary was also the first cousin of Hiram Revels, abolitionist minister and future first African-American member of the U.S. Congress.

Both Copeland and Leary were members of the Oberlin Anti-Slavery Society. Copeland had joined while in school at Oberlin College, which he attended from 1854 to 1855. Leary had joined shortly after his arrival in Ohio. In 1858 both men aided in the rescue of John Price, a freedom seeking enslaved man. Price was arrested in Oberlin, but was moved to Wellington, Ohio, as U.S. Marshals deemed Oberlin “too abolitionist” a place to incarcerate him. Shortly thereafter, members of the Oberlin Anti-Slavery Society attacked and overpowered his guards, helping him escape and eventually make his way to Canada. Thirty-seven men, including Copeland, were arrested and indicted for violating the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, although only two were ever brought to trial. Leary, although having been one of the rescuers, somehow managed to avoid arrest.

The Oberlin-Wellington Slave Rescue, as the event became known, likely solidified Leary and Copeland’s feelings. Shortly thereafter, Leary gave a speech to the Oberlin Anti-Slavery Society in which he stated, “Men must suffer for a good cause.” He also indicated that he had taken part in several attempts to aid freedom seeking enslaved people and often had “driven forth amid a shower of rifle balls.” Leary referred to his commitment as a “godlike calling.”

In March 1859, John Brown traveled to Cleveland, bringing with him eleven freedom seeking enslaved people that he claimed to have liberated in Missouri. Despite the hefty rewards offered for Brown’s capture, the local U.S. Marshal refused to intercede, citing the rising radical sentiment in the area. Raising funds for his future endeavors, Brown gave a public lecture at 25 cents a ticket. In the audience was Lewis S. Leary.

Later that summer, John Henry Kagi, one of Brown’s lieutenants and most fervent followers, met with John Mercer Langston, attempting to recruit several black people from Ohio for their party. Langston gave him several names, including Leary and Copeland, and promised to discuss the matter with them. In August Langston was visited by a gentleman who initially gave his name as John Thomas, but later admitted to being John Brown Jr. He told Langston, “My father is John Brown of Ossowatomie, who is ready to strike a blow which shall shake and destroy American slavery itself.” Brown had been given Langston’s name by Kagi, and had arrived to meet any potential recruits. Langston subsequently called on Leary and Copeland to come to his law office. Whatever Brown said was persuasive, or as Leary later noted “satisfactory.” Both young men made the fateful decision to John Brown’s “army” declaring their readiness “to die, if need be.”

On September 8, using a code developed among the conspirators, Leary wrote a letter to Kagi stating “I have a handy man who is willing and in every way competent to dig coal, but like myself, has no tools, his address is John Copeland, Jr., Oberlin, Ohio.” Leary and Copeland, having not informed their families of their decision, left Oberlin for Cleveland on October 6. In Cleveland they awaited several other recruits who failed to arrive. They subsequently headed to the Kennedy farmhouse, Brown’s headquarters near Harpers Ferry, where they arrived on October 15. The following evening, only one day after they had officially joined Brown’s force, the attack on the U.S. arsenal began.

Leary and Copeland were assigned, along with John Henry Kagi, to take control of Hall’s Rifle Works. They did so successfully during the night of October 16 but as dawn broke the following morning, it became apparent that they were cut off from the remainder of the party by the Virginia militia. The three men attempted to escape out the back door and across the Shenandoah River, but were caught in a hailstorm of bullets. Kagi was killed instantly and Leary fell severely wounded. Copeland escaped injury and dragged Leary to a rock in the center of the river. A local man named James H. Holt waded into the river and attempted to shoot Copeland, but his weapon misfired. Copeland attempted to return fire, but his powder had been fouled by the water. Copeland surrendered. Leary, mortally wounded, was dragged back to the riverbank.

Leary lived for a little over a day, until he succumbed to multiple gunshot wounds. It remains unknown where he was buried, but it is assumed he was interred in a common grave in Harpers Ferry. Copeland was placed under an armed guard throughout the night, but was nearly lynched by several town citizens. After Brown and the remaining conspirators surrendered the following morning, Copeland was placed with them.

One week later, Copeland, with Brown and three other survivors, was indicted for treason, murder, and inciting a slave insurrection. Ironically, the first charge, treason, was later dropped against him and Shields Green, an enslaved man seeking freedom also from Oberlin, on the grounds that, as black men, they were noncitizens and therefore could not be treasonous.

During the subsequent trial that led to his conviction and sentence of death, Copeland impressed many of those who witnessed his spirited defense. The prosecuting attorney later wrote,

From my intercourse with him I regard him as one of the most respectable persons we had. . . . He was a copper-colored Negro, behaved himself with as much firmness as any of them, and with far more dignity. If it had been possible to recommend a pardon for any of them it would have been this man Copeland as I regretted as much if not more, at seeing him executed than any other of the party.

On December 16, 1859, Copeland was hanged at the gallows in Charlestown. On his way to his execution he reportedly exclaimed, “If I am dying for freedom, I could not die for a better cause -- I had rather die than be a slave!” After the execution, Copeland’s body, along with the corpse of Shields Green, was dug up and taken to the Winchester College Medical Laboratory in Winchester, Virginia, where it was dissected as a medical cadaver.

Both men were hailed as heroes in Oberlin. Democratic newspapers however slammed the progressive community. Cleveland’s National Democrat wrote “The blood of the poor ignorant blacks, Leary and Copeland, will forever stain the character of the whites of Oberlin and other places in Ohio.” Another editorial proclaimed “Oberlin is the nursery of such men as John Brown and his followers. Here is where the younger Browns obtain their conscientiousness in ultraisms, taught from their cradle up, so that while they rob slaveholders of their property, or commit murder for the cause of freedom, they imagine they are doing God’s service.” John Mercer Langston and other black leaders did not shy away from these accusations. In a speech shortly afterwards he proclaimed, “We most cheerfully approve of the manly, the heroic, the patriotic, and the Christian course pursued by the noble and Christ-like John Brown and his compatriots.”

Both men’s families carried on their dreams and aspirations. Copeland’s family showed their support by taking up arms during the Civil War. His father, John Copeland Sr., served as a cook for the 55th Ohio Infantry, while his younger brother Henry E. Copeland served from 1864 to 1865 as a first sergeant in Douglass’s Independent Battery of Colored Artillery in Kansas.

Leary left a widow and a six-month old daughter named Lois. In January 1869, the Lorain County News announced the notice of “marriage of Charles Langston, Esq., brother of John M. Langston, and Mrs. Mary S. Leary, the widow of Lewis Leary, one of John Brown’s raiders who was shot while upon the rocks at Harpers Ferry.” Charles and Mary settled in Kansas and three years later had a daughter named Caroline Mercer Langston, who became the mother of the Harlem Renaissance poet, playwright, and author Langston Hughes.

Leary’s family in Fayetteville remained in North Carolina during the Civil War. Little is known of how they were treated following the news of John Brown’s raid and their son’s death. During Reconstruction, both Leary’s father and his older brother served as county commissioners for Cumberland County, as well as city councilmen for Fayetteville. His brother Matthew, Jr., served as one of the founding trustees of what became Fayetteville State University.

Leary’s youngest brother, John Sinclair Leary, graduated from Howard University in 1871 and was one of the earliest black attorneys admitted to the bar in North Carolina. He served in the state legislature for two terms as a Republican representative for Cumberland County during Reconstruction, and in 1884 was sent as a delegate to the National Republican Convention. He later founded and served as the first dean of the Shaw University Law School, and in the 1890s moved his family and practice to Charlotte. Today the Charlotte chapter of the North Carolina Association of Black Lawyers is named the John S. Leary Bar Association in his honor.

The two young North Carolinians of Brown’s party did not die in vain. By the conclusion of the war, their dream of an emancipated population had been realized. Still, they remained little honored, and were largely forgotten outside of their home community. In 1865, an obelisk honoring Copeland, Leary, and Shields Green as “These colored citizens of Oberlin, the heroic associates of the immortal John Brown, gave their lives for the slave” was placed in Westwood Cemetery in the town. The monument was moved nearby in 1977 to a more prominent spot in what is now Martin Luther King Park.

Leary and Copeland were key players in one of the most important events in the nation’s history. John Brown’s raid escalated the tensions leading to secession and the American Civil War. Historian David Potter argued in his landmark work, The Impending Crisis, that the emotional effect of Brown's raid was far greater than that of the Lincoln-Douglas debates and that it further heightened the deep division between North and South to the point of no return.