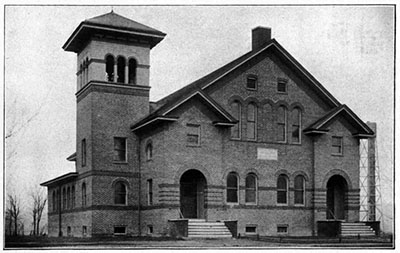

The origins of the Brick School can be traced to the philanthropy of Julia Elma Brewster Brick of New York and the work of the American Missionary Association. Julia Brick approached Howard University and expressed a desire to donate land she had acquired in North Carolina to create a school for poor black children. She was referred to the American Missionary Association, a philanthropic organization that developed numerous schools in the South after the Civil War. She donated land, some of which was sold to fund the new school, to the Association and Thomas Inborden was sent to North Carolina along with five teachers in 1895 to begin the school. The school benefited from her benevolence throughout her lifetime, receiving numerous financial donations to meet its growing needs.

Inborden was born in 1865 to freeborn parents and had been schooled at Oberlin College and Fisk University

before he joined the American Missionary Association to assist in their goal of educating minorities. The new school in what is now known as Bricks in Edgecombe County was organized under Inborden’s leadership and called the Joseph Keasbey Brick Agricultural, Industrial and Normal School. During the school’s first year, it enrolled fifty-four students, some boarders and others living at home in the local area. The school was coeducational and accepted students up to the fourth grade.

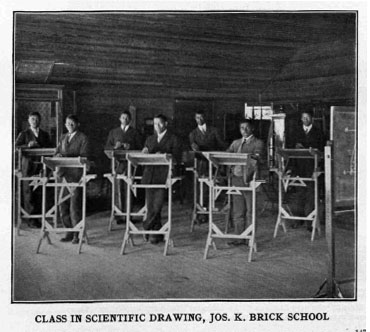

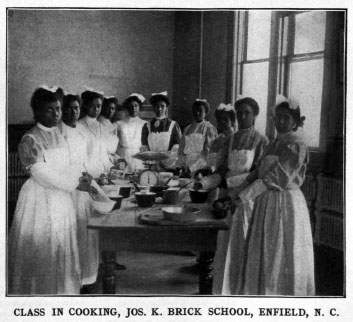

The institution eventually boasted over one thousand acres, three large dormitories, educational buildings, and shops. Students supplemented the traditional school curriculum by training in various trades such as blacksmithing, woodwork, mechanical drawing, and cabinetmaking. The dual educational approach benefited the school since a variety of farm products were produced to support its programs. In addition, the school had a strong business in mail-order honey sales. Interest in the school boomed and, at one time, enrolled as many as 460 students.

Inborden and others worked to make the school succeed and in 1926 it was made a junior college. However, due to financial difficulties and decreasing enrollment during the Great Depression, the Brick School was forced to close its doors. Although the school closed, it is credited with being a pioneer institution of education in eastern North Carolina and is recognized for educating many African Americans in the region.