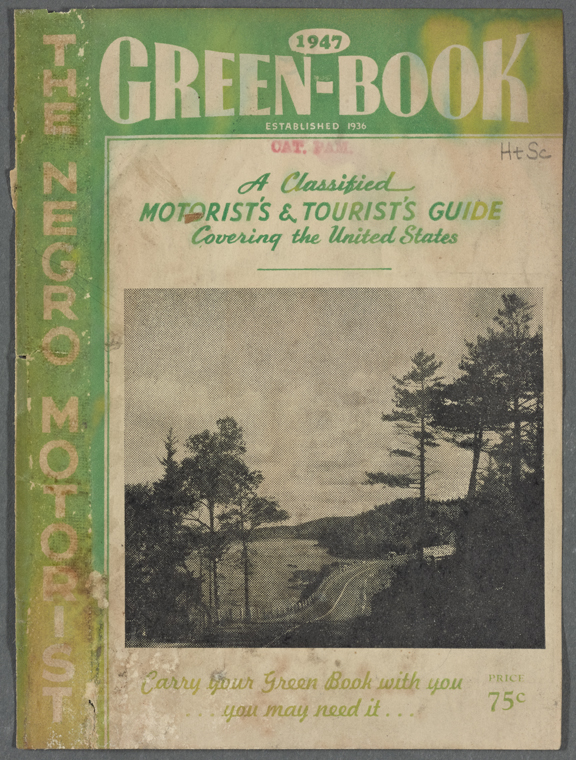

The Green Book, also known as The Negro Motorist Green Book, later known as The Negro Traveler’s Green Book in 1952, and finally the Travelers’ Green Book in 1960, was a guide for black travelers journeying within the United States and abroad. New York native, World War I veteran, and postal carrier, Victor H. Green, conceived of the book in 1932 as a preventative measure to embarrassments, difficulties, and critical safety concerns black travelers faced as they traveled the racially segregated United States. The first copies of the guidebook, 1936 and 1937, mentioned only New York City, southern New York, and New Jersey. In 1938 The Green Book expanded to include some of the Mideast and most of the East coast, North Carolina included. North Carolina’s addition encompassed eight cities: Fayetteville, Gastonia, Greensboro, New Bern, Raleigh, Sanford, Winston-Salem, and Weldon. As more patrons and Green Book staff traveled, the number of states and cities increased. It also offered advice on topics from car maintenance and safe driving to rights black people were entitled to in the North, West, and Midwest. The book was noted by many to be an absolute logistical and safety necessity for survival while on the road traveling.

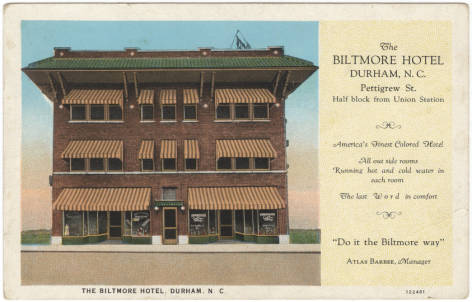

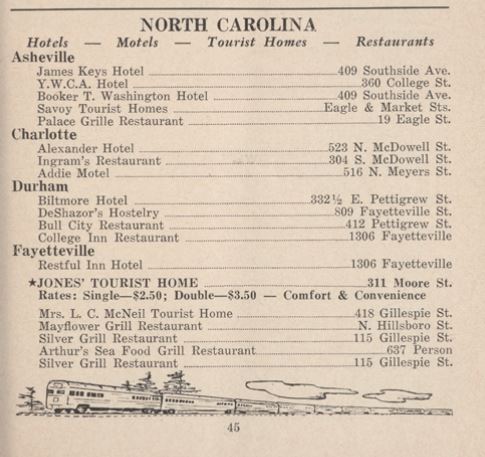

One of the difficulties black travelers encountered was finding a place to stay. Across the country, some hotels and tourist homes would not serve black customers, and in many areas black travelers faced threats and violence in trying to secure gasoline, car maintenance, meals and accommodations. In order to avoid a search for a place to stay, or sleeping in one’s car, The Green Book listed hotels, tourist houses, and taverns that served Blacks. Some North Carolina establishments were the Lightner Arcade and Hotel (Raleigh), The Biltmore Hotel (Durham), the Rhone Hotel (New Bern), and the Magnolia Hotel (Greensboro). The Rhone Hotel and Magnolia Hotel still stand today.

Located on Raleigh’s East Hargett Street, the Lightner Arcade and Hotel was in the center of the city's black business and cultural district. The Arcade and Hotel housed famous musicians such as Duke Ellington and Count Basie. It is no longer standing. It was bought out in the 1960s, and in 1970 a fire destroyed the building.

In Durham, The Biltmore Hotel was built in 1929 on the edge of the Hayti neighborhood, what was once the heart of the city’s African American cultural and business community, and was advertised as “America’s Finest Colored Hotel”. Like the Lightner, The Biltmore hosted popular musicians and was more than a hotel – it housed a drugstore and grill and coffee shop. In 1977 The Biltmore was demolished when the neighborhood was destroyed to build NC Highway 147, the Durham Freeway.

The two locations that still stand today are New Bern’s Rhone Hotel and Greensboro’s Magnolia Hotel. The Rhone Hotel was owned by sisters, Amy, Charlotte, Henrietta, and Carrie Rhone. It opened in 1923 on Queen Street and was a great help to the estimated 3,000 people who lost their homes in a fire in 1922. The Magnolia Hotel was established around 1949. Like the Arcade and The Biltmore, the Magnolia Hotel housed black luminaries such as Ray Charles, Tina Turner, Martin Luther King Jr., Jackie Robinson, and James Baldwin. It is estimated that the hotel stopped operating in the sixties or seventies. In 1998 construction began to restore the house and today the hotel is a place to dine, host events and meetings.

The Green Book received advertising sponsorship from a variety of businesses, both black and white owned. This included several African American newspapers as well as the petroleum and service station company Standard Oil/Esso. The 1949 edition even included an endorsement by Esso and the publication was sold in Esso service stations. In fact, the Esso company was a leader in breaking the racial barrier in the 1940s as blacks became franchise owners and held positions as scientists, engineers, and in marketing.

At its height, the publication sold around 15,000 issues per year, and eventually the Green Book included international destinations -- Canada, Mexico, and Bermuda. In the 1960s following passage of the Civil Rights Act, The Green Book also took on the role of listing states that continued to uphold Jim Crow era laws and practices. Inclusion of a “Civil Rights” section was particularly evident in the 1963, 1964, 1966, and 1967 editions. Among these newly articulated rights are refusing to serve black people service at hotels. The book helped give black Americans concrete steps for recourse by presenting state departments, fair right commissions, fair employment practices and commissions that travelers could go to report violations. The 1966-1967 edition was the last year of publication, appearing under the title Travelers' Green Book: 1966-67 International Edition: For Vacation Without Aggravation. The inclusion of the Civil Rights section, international travel, the final title and termination of the publication were all indication of the evolution of the publication and changes in law and society. Over the course of its publishing history, the publication's title appeared with a few spelling variants: Green-Book and Green Book.

To explore online collections of the Green Book, visit:

The Green Book, New York Public Library Digital Collections: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-green-book

Navigating the Green Book: https://publicdomain.nypl.org/greenbook-map/trip.html

University of South Carolina Green Book Interactive Map: https://digital.library.sc.edu/collections/the-negro-travelers-green-boo...

North Carolina African American Heritage Commission Green Book Project: https://aahc.nc.gov/green-book-project

Interactive Map of Route 66 Green Book locations, National Park Service: https://www.nps.gov/maps/full.html?mapId=68beff0c-3eda-4c6e-89c1-8e48135c2e89