Penderlea

"Yesterday and Today"

by Ann Southerland Cottle

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2010.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: Penderlea Homesteads

The northwestern corner of Pender County may seem an unlikely spot for a somewhat radical government experiment. But ingenuity, hard work, and investment by the government and Wilmington businessman Hugh MacRae aimed to turn a largely unsettled area there into productive farms and homesteads at the height of the Great Depression.

The northwestern corner of Pender County may seem an unlikely spot for a somewhat radical government experiment. But ingenuity, hard work, and investment by the government and Wilmington businessman Hugh MacRae aimed to turn a largely unsettled area there into productive farms and homesteads at the height of the Great Depression.

The quiet agricultural community of Penderlea was the first of five “farm cities” established under the United States Department of the Interior’s Division of Subsistence Homesteads in 1934. The government designed such “resettlement” projects to provide jobs for thousands of out-of-work men, as well as modern new homes and land for tenant farmers renting small farms or part-time farmers struggling to scratch out a living from worn-out soil. The plan: the community would be able to support itself without outside help. Homesteaders would grow produce like beans, squash, cucumbers, corn, and strawberries. What the community did not need, farmers could sell as part of a distribution system that included nearby railroads. Trees cleared for farmland could become building and furniture material.

The federal government handpicked Penderlea’s homesteaders, who were white and Protestant. Each family had to be poor and include children. The more children a family had (especially boys), the better its chance of being chosen. Families had to get recommendations from a government agent who visited them unannounced to make sure everything in their home matched their application; from their church pastor; and from a North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service agent. Once a family received an invitation to live on Penderlea, its members had to pass physical exams given in Burgaw. Some of these requirements contributed to Penderlea’s success for some families, but in reality, officials excluded other citizens. At low prices, the government bought out the few black families who had lived in the area and farmed it for many years, moving all African Americans off the project. No Jewish or Catholic family, no single person, and no married couple without children was chosen.

Penderlea was MacRae’s American dream come true. He believed that such communities could provide a good living, as well as a good social example in the rural South. Times had been hard for decades after the Civil War. The struggle to survive became even greater during the Depression. Unemployment skyrocketed. Foreclosure—when an owner’s home or farm is taken and sold to meet payments due—became a dreaded word. MacRae already had spent over $1 million trying to copy the success of small European farms in several communities in the Cape Fear area. When he bought 10,000 acres called the Wilson Tract in Pender County, he hired experienced town planners to help design what became Penderlea. An amendment to the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and congressional action in 1934 let President Franklin Delano Roosevelt spend $25 million to develop “farm cities” to draw people from overcrowded urban areas and help struggling farmers. MacRae sold 4,500 acres to the federal government at a loss, and the government hired him to oversee Penderlea’s beginnings. Different federal agencies took charge over the next few years.

The government placed ads for Penderlea in newspapers and magazines. People from as far away as Kansas responded. Chosen homesteaders came from all over North Carolina and South Carolina, with a few from other states. Shortly after construction began in spring 1934, Sut and Katie Bell Austin and their young son, Nick, moved in. Bruno and Jo Van Bavel, with their daughter, Peggy, son, Buren, and soon another newborn son, Frank, followed. The families lived in two-room tarpaper shacks on runners until workers finished their houses. Sut Austin used to joke that they lived in the first mobile homes. “We could move those shacks anyplace we wanted to,” he said. The families kept a cow hidden in the woods nearby, milking her before daylight and after dark. The government said only purebred livestock could be brought to Penderlea, but homesteaders could not afford purebred cows, horses, mules, or hogs. The project manager found out about the cow only after homesteaders convinced officials to change the rule.

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers lived in five new barracks while they built three main roads, over 100 miles of ditches, and 15 miles of canals. Up to a thousand men, white and black, worked on the project, including hundreds from the surrounding area and homesteaders themselves. One crew worked ahead of the machinery, removing shrubs, wild flowers, and trees that could be cared for in a nursery at the barracks, then used for landscaping the new homes.

MacRae believed that for a rural civilization to be socially satisfying, the woman in each family must be given “a house in which she is perfectly happy; wants very badly, and in which her interest will never wane.” His “six essentials to health and contentment” included food in variety and abundance; shelter with attractive surroundings; warmth from a surplus of good fuel; education for children; good social conditions; and freedom from fear about the future. He butted heads with government officials to include things considered luxuries “in the country” in the early 1930s: electricity, indoor running water, and indoor toilets.

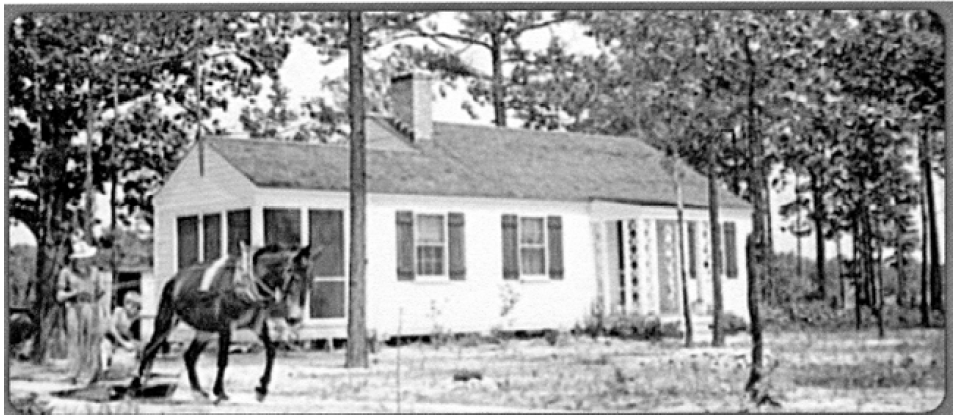

Eventually about 190 of the planned homes were built, on 10-acre or 20-acre plots. MacRae was precise about how and where he wanted homesteads built. Each would face a road. The single-story houses, 1,000 to 1,400 square feet, used six basic floor plans. They had wood siding, painted white with green or black shutters. The first 10 houses had cathedral ceilings, oak and hardwood floors in the living rooms, a screened porch, a small kitchen, a tiny dining area, two bedrooms, a small room for the toilet, and a small room for the claw-footed bathtub and sink. Bedrooms boasted overhead light fixtures; the master bedroom had a sink; and the second bedroom had two closets. Heat came from wood-burning heaters. The next houses built were less expensive, sometimes with more bedrooms but fewer features—open fireplaces provided heat, for example, until families could afford heaters. Wood cookstoves helped heat all the houses, which had no insulation. Cold wind blew through the tongue-and-groove pine board walls. Children liked to play behind the warm stoves and sometimes fell asleep on the floor beside the chimney. Each homestead included a livestock barn with a hayloft, poultry house, hog house, corncrib, washhouse, smokehouse, and pump house.

On June 11, 1937, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt—who had helped convince her husband that farm cities were good ideas—visited. Homesteaders spent many days preparing, even writing a play about their lives before and after moving to the project. Mrs. Roosevelt arrived on the train at Wallace at 7 a.m. Penderlea farm manager C. R. Dillard said his job that hot day was to drive a truck in front of the convertible she was riding in, spraying the road with water to keep the dust down. (Depending on the weather, deep sand or mud covered the unpaved roads.) People lined the streets in Wallace and all the way to Penderlea, trying to glimpse Mrs. Roosevelt. Everyone who met her said she was gracious and proud of the project.

On June 11, 1937, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt—who had helped convince her husband that farm cities were good ideas—visited. Homesteaders spent many days preparing, even writing a play about their lives before and after moving to the project. Mrs. Roosevelt arrived on the train at Wallace at 7 a.m. Penderlea farm manager C. R. Dillard said his job that hot day was to drive a truck in front of the convertible she was riding in, spraying the road with water to keep the dust down. (Depending on the weather, deep sand or mud covered the unpaved roads.) People lined the streets in Wallace and all the way to Penderlea, trying to glimpse Mrs. Roosevelt. Everyone who met her said she was gracious and proud of the project.

In August 1937 construction began at the center of Penderlea on a modern, single-story school complex, which would combine the enrollment of several smaller schools. Six hundred students started the year in temporary spaces like the workers barracks and potato house until the 26 classrooms were finished. Classrooms opened to the outside, connected by covered cement walkways. A community library separated the high school from the elementary area for grades 1–8. With more than 6,000 volumes, it was one of the largest rural school libraries in the state. The homesteaders took (and take) great pride in the school and library, which hosted many banquets and proms. The first graduation ceremony was held there in May 1938 after rain slowed completion of the auditorium. One mother whose daughter graduated said it had been raining for days. Boards laid on the ground outside to keep feet dry sank in the deep water.

The campus also had craft, music, and band rooms, a large gym, a home economics area with three kitchens and a big sewing room, a vocational shop, a school bus garage, and a teacherage (cooperative residence for teachers). Furniture was built in the vocational shop; today people treasure these simple oak and maple pieces. Nearby were a community building, a health clinic, a potato-curing house, a cane-syrup mill, a cannery, a cooperative store (called “the big store”), a warehouse, a gristmill, a vegetable grading house, and a three-bedroom house for the school principal.

Penderlea was a close-knit community. Families worked and played together. Social events included barn raisings, square dances at the CCC barracks, and plays in the school auditorium. Women met at home extension clubs to make quilts, mattresses, and even furniture. Children had 4-H clubs, Girl Scouts, and Boy Scouts. During hot summer evenings, neighbors often sat together under shady trees, hoping to catch a breeze. No one had electric fans, and few residents had a refrigerator for ice. After church services, settlers spent the afternoon visiting and enjoying a picnic dinner under the big oak trees. During the summer, boys would slip off to Giddeons Pond to swim. Sometimes they camped out, surrounded by woods. Snakes and other creatures liked the pond, too, which was enough to keep the girls away.

Families raised their own meat. When the days turned cold, neighbors helped each other with hog killings. Ham or sausage with eggs, grits, red-eye gravy, hot biscuits, and homemade jelly. Cornmeal was ground at the community mill, as were flour and feed for the animals, all bagged in cotton feed sacks printed with different patterns. Women made curtains, aprons, housecoats, pillowcases, and clothes from those sacks. Young girls often went to the mill to pick out the sacks they wanted for their clothes. It took about three sacks to make a dress.

Farmers at Penderlea quickly found out that they could not survive and pay their bills growing just produce and the cut flowers and bulbs they had begun to ship north. Most homesteaders had been tobacco farmers, so they built tobacco barns and began to make a little money to pay their bills each fall. Others worked at the hosiery mill built by the government in 1938. During the late 1930s and 1940s, there were 50 or more dairies on the project as families renovated their barns into milking parlors and added a room for the milk room.

Penderlea has changed in some ways, and in other ways, not at all. Many of the original homes were sold and moved off the project in 1945, when farms were combined to provide more acres per unit. Several roads on the old Penderlea Homestead map have become paths, and most of the roads are paved. The mule has been retired. Air-conditioned tractors pull eight or more plows through fields at one swipe. Most farmers contract to grow hogs, chickens, or turkeys in long buildings. Many residents work elsewhere. The school is a year-round, grades K–8 campus. A few early homesteaders remain, and others are second- and third-generation descendants. Ultimately, people viewed resettlement experiments like Penderlea as failures. But at Homecoming, the first Sunday in November, the sanctuary at Potts Memorial Church overflows with former members and Penderlea residents who have come “home.”

*At the time of this article’s publication, Ann Southerland Cottle, a Penderlea resident since the age of 4, was a retired high school English and drama teacher. Her interest in history led her to write The Roots of Penderlea, which documents the history and firsthand accounts of the Penderlea homestead project.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: What is the American Dream?. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/AmericanDream.pdf

Image Credits:

"Residents of Penderlea Homesteads enjoy a Sunday school picnic in 1937.'" Image from the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-DIG-fsa-8a17327.

"An early home built at Penderlea." Image from Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF33-T01-000717-M2.

Additional resources:

Penderlea Homestead Museum: http://www.penderleahomesteadmuseum.org/

1 January 2010 | Cottle, Ann Southerland