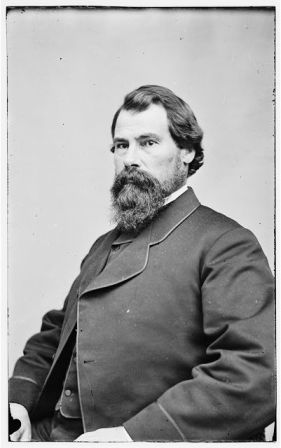

According to the Confederate Provisional Constitution that was adopted on 8 Feb. 1861, the postal service was to support itself from its own revenue. The Confederate Post Office Department was established on 21 February, and John Henninger Reagan was appointed the first postmaster general. On 27 May North Carolina entered the Confederacy, and on 1 June the Federal postal system was ordered to cease operations in the southern states. Reagan's first actions were to ask existing postmasters and route agents to stay on at old U.S. contracts. He negotiated a 50 percent reduction in the railroad rates for carrying the mail, and, most important, he increased the postal rates from three cents to five cents per half-ounce letter sent less than 500 miles and ten cents if sent farther than 500 miles. It was October 1861 before the first postage stamps were available for use by southern citizens.

In its first year of operation the post office sold $692,067 in postage stamps and in the second year, $2,392,332. The discrepancy can largely be explained by the fact that stamps were unavailable during much of the first year and the postal rate was increased to ten cents for any distance on 1 July 1862. However, postage stamps began to play another important role in the community, as many were used as small change in lieu of available coins.

Mail was carried on the rail lines in specially built mail cars. Route agents traveled in these cars to sort and process the mail along the way, a most unpleasant job. On a good day the route from Goldsboro to Charlotte made 23 stops and took 15 hours. Mail carriers worked seven days a week. Most mail cars had no heat, and the War Department frequently used them to ship dead soldiers home. Complaints were the norm for many route agents. By the end of the war, when almost all materials were in short supply, letters and envelopes turned inside out were reused. It was not uncommon to see a letter written in one direction, turned sideways, and written in the other direction to conserve paper.

Confederate postal operations made a profit every year-something that the U.S. postal system had never done. In the process, however, the Post Office Department sacrificed service for efficiency and economy. By the end of the war, migrating Confederate soldiers were carrying more mail than the postal system. Postmaster General Reagan had accomplished his goal of profitability, but at the expense of the citizenry.