Classification

Class: Mammalia

Order: Rodentia

Average Size

Length: 10 ¾ to 12 ¼ in.

Weight: 3 ½ to 4 ¼ oz.

Food

Fungi, particularly mycorrhizal fungi, lichens, conifer and hardwood seeds, fruits, insects, tree buds, and some animal matter.

Breeding

Gives birth to litters of 2 to 4 young following a gestation of 37 to 42 days. One to two litters per year, with the first litter in May or June and the second in the summer.

Young

Weigh about ¼ of an ounce and are about 2 ¾ inches long at birth. Eyes open at 1 month, weaning occurs at about 2 months.

Life Expectancy

Some northern flying squirrels live for 6 or 7 years, but most do not live that long.

How far can they glide?

Flying squirrels drop about a foot for every three feet of forward glide. Glide distance depends on terrain shape and height of the take off tree. They can not gain altitude.

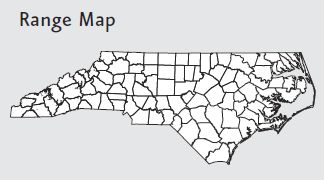

Range and Distribution

The northern flying squirrel is found across Canada and the northern United States, its range extending southward in the great mountain chains of North America. North Carolina is the southern extent of this species in eastern North America, with the Carolina subspecies distributed in western North Carolina, east Tennessee, and southwest Virginia. In North Carolina the squirrel is isolated in small populations on the highest mountains. It had a wider range at these latitudes tens of thousands of years ago during glacial times when boreal forest was much more extensive.

History and Status

Biologists first discovered the Northern flying squirrel in North Carolina in the early 1950s. The animal was already known from a wide area of northern North America as a common inhabitant of coniferous and mixed coniferous- deciduous forests. The squirrel was found in three areas of the southern Appalachi ans: Mount Mitchell, Roan Mountain, and the Great Smoky Mountains. While biologists thought the squirrel likely occurred on high mountains throughout the region, it was not until the federal government declared the Northern flying squirrel an endangered species in 1985 that funds became available to study its distribution. Subsequent studies found the species in a total of eight mountain ranges: Long Hope, Roan, Grandfather, and the Black-Craggy Mountains north and east of the French Broad River Basin, and Great Balsam, Plott Balsam, Smoky, and Unicoi Mountains south and west of the French Broad River Basin.

Description

Northern flying squirrels have bright cinnamon brown colored fur dorsally, gray fur around the face and the end of the tail, and bicolored fur on the belly that is gray at the base and creamy white at the tip of each hair. This squirrel’s most distinctive feature is the cape of loose skin that stretches from its wrists to its ankles and forms the membrane on which it glides. The squirrel has a long, flat, furred tail.

The northern flying squirrel superficially resembles the smaller, more common southern flying squirrel (Glaucomys volans). Adult northern flying squirrels are almost twice the weight of adult Southern flying squirrels. While there is some elevational overlap in their range around 4000 to 5000 feet, northern flying squirrels are restricted to the highest elevations while southern flying squirrels are found most commonly at low to mid elevations.

Habitats and Habits

The northern flying squirrel inhabits the cool, wet boreal and deciduous forests of North Carolina’s highest mountains. It prefers a mix of conifers (red spruce, Fraser fir, Eastern hemlock) and northern hardwood trees (yellow birch, buckeye, sugar maple). Biologists have found that the squirrel forages in the conifers and dens in the hardwoods. Dens are found in live and dead trees and include old woodpecker cavities, rotted knotholes where branches have broken off, hollow and split tree trunks, and subterranean rock dens. The squirrel builds a distinctive nest of finely shredded yellow birch bark that may be used for denning or rearing young. It also constructs stick nests, called “dreys”, in the dense foliage of conifer limbs during the warmer months. The stick nest is lined with shredded birch bark. Individual squirrels usually have 3 to 8 favorite den sites and move freely between dens, often sharing a nest with other squirrels.

Gliding to Food

Northern flying squirrels are nocturnal, emerging from their dens just before dusk to forage. They do not store food in their dens, however, and take off from the nest to a favorite feeding area. Traveling quickly, they sail from the tops of trees by pushing off with powerful hindquarters, spreading all four legs, and gliding to the ground or the base of a nearby tree.

The northern flying squirrel eats many different kinds of foods, and some of its favorite foods are fungi. Mycorrhizal fungi grow in association with the roots of plants. The fruiting bodies, called truffles, are found underground and emit a strong odor that attracts squirrels. The squirrel’s keen sense of smell and gliding ability allow it to seek out fresh “blooms” of aromatic truffles across its home range. This “tree squirrel” actually spends most of its waking hours on the ground, digging for truffles and searching for other food items. Trees need mycorrhizal fungi to grow, and mycorrhizal fungi need an animal to disperse their spores. In effect, the squirrel perpetuates its own forested habitat through its consumption and dispersal of these fungi.

In spring, female northern flying squirrels give birth to two to four young. Second litters are possible if the female is in good nutritional condition. Young squirrels are helpless at birth and depend completely on their mother’s care. Eyes open when the squirrel is a month old. Nursing stops a month later, at which point young squirrels first begin jumping and gliding short distances.

People Interactions

Most North Carolinians never see the northern flying squirrel because it lives in the high mountains and it is nocturnal. We have affected the squirrels’ habitat in several ways. Logging and subsequent fires during the early part of this century changed large areas of high elevation forests in the Great Balsam and Black Mountains. These forests are still recovering from that disturbance. The balsam woolly adelgid, an insect pest, has infested and killed most of the mature Fraser fir stan

ds in North Carolina. The hemlock woolly adelgid is currently decimating hemlock stands. Fortunately, for the squirrel, it can also live in northern hardwood and red spruce forest.

NCWRC Interaction: How You Can Help

Volunteer to check flying squirrel boxes.

Volunteers are needed to help biologists check squirrel boxes for the endangered Carolina northern flying squirrel each winter. Squirrels are captured, measured, marked, and released as part of this monitoring project. This project requires a full day in the field, and the abilities to hike in steep, slippery terrain, work in extreme cold weather, and haul heavy equipment. Contact NCWRC for information.

Volunteer to build flying squirrel boxes.

Each year, NCWRC biologists check several hundred flying squirrel boxes. Boxes require regular repair and replacement as they become worn and weathered. Contact NCWRC for information and box construction plans.