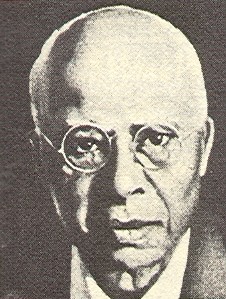

15 Aug. 1866–2 May 1945

Monroe Nathan Work, bibliographer and historian, was born in Iredell County, the son of Alexander and Eliza Hobbs Work, both of whom were enslaved until the end of the Civil War. He was the youngest of eleven children, six girls and five boys. In 1866 Alexander Work moved to a farm near Cairo, Ill., where his family joined him in 1867.

In 1876 the Works moved to Sumner County, Kans., where Monroe completed his elementary education. As the youngest son, he worked on the family farm until the death of his mother in 1889, when at age twenty-three he entered high school in Arkansas City. An excellent student, he was graduated at the head of his class in 1892. After trying his hand at both teaching and preaching, he entered the Chicago Theological Seminary in 1895 and was graduated in 1898. Deciding that he was not intended to be a minister, he entered the University of Chicago, paying his way by working as a janitor. He took most of his courses in the social studies and received Ph.B. and M.A. degrees in 1902 and 1903, respectively.

In the fall of 1903 he became instructor of history and pedagogy at Georgia State Industrial College, in Savannah, where he remained until 1908. On 27 Dec. 1904 he married Florence Evelyn Henderson of Savannah.

While at the University of Chicago Work began research and writing in the field of Black history and sociology with an article on "The Negro and Crime in Chicago," published in the American Journal of Sociology in September 1900. Continuing this interest at Savannah, he attracted the attention of Booker T. Washington, who invited him to join the faculty of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

In September 1908 Work became director of the Department of Records and Research at Tuskegee, a position he held until his retirement thirty years later. Charged with collecting, recording, and preserving the history of Black life in America, he began in 1912 to publish The Negro Yearbook, a compilation of information and statistics on Black life in America: economic, social, and historical. Of particular interest was his continued record of lynchings in the United States. Work wrote widely for periodicals and newspapers, especially the Southern Workman, published at Tuskegee, and the Journal of Negro History. He was also instrumental in 1915, along with Washington, in starting the annual National Negro Health Week, an event later sponsored by the U.S. Public Health Service.

In 1928 Work published his major contribution to scholarly research, Bibliography of the Negro in Africa and America, which contained over 17,000 entries, including many rare items found in a tour of European libraries. A review of this work called it "the whole history of the Negro race in outline." The next year he received the William E. Harmon Award for the Negro Year Book and Bibliography. Among other honors, he was awarded the University of Chicago Alumni Citation (1942) and the D.Litt. degree from Howard University (1943). In 1942 Mrs. Betsy Graves Reyneau painted his portrait for the Smithsonian exhibition, Portraits of Outstanding Americans of Negro Origin, funded by the Harmon foundation.

At various times he was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Academy of Political and Social Science, American Economic Association, American Sociological Society, International Institute of American Language and Culture, Southern Economic Association, Southern Sociological Society, NAACP, and other organizations.

Work died at his home in Tuskegee and was buried in the cemetery on the campus. His wife died on 27 June 1955. They had no children.